|

Socio-Political Issues

Eric Gill, a Precursor of Vatican II

Patrick Odou

There are still some Traditionalists who are promoting Eric Gill as a Catholic leader. To them, the fact that he was a blasphemer, a homosexual, and an incestuous pedophile is not sufficient reason to reject Gill and his views. They see his moral atrocities as “personal faults.” To those who would take Gill for an evil man, they turn up their noses and say: “I’m not interested in Gill’s personal life. I’m only interested in his ideas.” The implication is that his ideas are acceptable. They pretend that a stone wall stands between a man’s morality and his ideas, and that one does not influence the other.

Above, in 1940, Eric Gill poses wearing his eccentric cassock and sandals in a pre-hippy style |

Even if I admit that, in theory, a certain distinction between the two fields can be made, on a practical level I think that the different aspects of one’s personality are interrelated and, in different proportions, are able to define him. In the case of Gill, his pornographic art was clearly a reflection of his morally perverted life, as I previously demonstrated. Now, I sustain that the same can be said about his ideas – they were also very bad. In order to prove my point, let me discuss some of these ideas here.

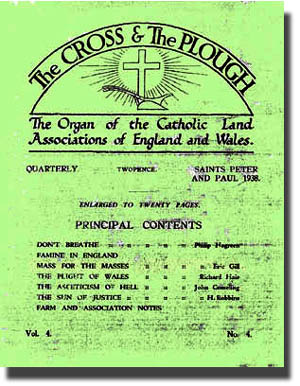

At the age of 56, Eric Gill wrote the article Mass for the Masses (1). The year was 1938, 25 years after his conversion and just two years before his death. So, at this stage of his life, one may assume his ideas were fully formed. The work was published in the Distributist organ The Cross and the Plough, which was a quarterly magazine that promoted “Back to the Land.”

In Mass for the Masses, as we shall see, Eric Gill promoted not only the “Back to the Land” movement, but also the progressivist liturgical reforms that later would be officially approved by Vatican II.

Basically, Mass for the Masses takes the same presupposition of today’s progressivists, that is, that in the late 19th century and early 20th century the Church supposedly did not attract the workers to her bosom as she should have done. So, they purport, she was failing in her mission, and therefore her methods must change. To solve this supposed problem, a new solution was necessary: Distributism in society, and reform in the Catholic Church.

The Cross and the Plough featuring Gill's article "Mass for the Masses," vol. 4, 1938 |

Fundamentally, I think that this problem was, and still is, poorly presented. It was poorly presented in England and in France.

In England, the social and economic crisis of the workers in the 19th century, which gave rise to Marxism, was mostly a consequence of a Protestant input regarding capital and work. As is known, Protestants encouraged all types of economic ambitions and profits without due concern for the inhuman consequences that could affect workers. Therefore, the Catholic Church cannot be blamed for a crisis that was a consequence of the Protestant mentality and its work ethic.

In France and other Catholic countries of Europe, the so-called social and economic problem of the 19th century and early 20th century was, in my opinion, primarily a consequence of the abandonment of Catholic principles by owners as well as workers. As a result of the widely spread egalitarian teachings of the Enlightenment translated into facts by the French Revolution, the previous harmony among social classes ceased. Both owners and workers were told that they were equal, and an atmosphere of self-sufficiency was established.

This romantic doctrine that all men are equal generated, nevertheless, an inevitable difference: when an owner proceeds self-sufficiently, he often succeeds; however, when a worker proceeds self-sufficiently, he often comes to a grinding halt. As a result, we witnessed a crisis: the success of many owners and the failure of countless workers. Then an “explanation” was invented: the reason for the workers’ failure was due to the selfishness of the owners, and not to the false doctrine of the Enlightenment.

Very often, Catholic Pastors failed to denounce the real cause of that social and economic crisis. Almost no one pointed to the egalitarian doctrine of the Enlightenment as the source of the problem.

The above, in my opinion, constitutes the true and false presentations of the social and economic crisis of the worker in Catholic countries.

1974 - Members of the French JOC sing the International Communist to celebrate the 50th anniversary of their Catholic Worker organization - Informations Catholiques Internationales, July 15, 1974 |

Modernist leaders, followed by their progressivist heirs, spread this false presentation of the workers’ problem and, of course, advocated a change in the previous social doctrine of the Church. The 1920s and 1930s saw in France a fermentation of ideas among Catholics that gave birth to such movements as the progressivist JOC – Jeunesse Ouvrieres Catholiques [Catholic Youth Workers] and its co-related JUC – Jeunesse Universitaire Catholiques [Catholic University Students] that walked hand-in-hand with Communists in their social demands. These movements were the followers of the modernist Le Sillon, condemned by St. Piux X in the apostolic letter Notre charge apostolique, and the precursors of the priest-workers of the ‘50s. Vatican II with its Pastoral Constitution Gaudium et spes would mark the victory of this progressivist current.

In the ‘20s and ‘30s, Eric Gill (see Mass for the Masses, p. 7) and other Distributist leaders in England assumed the very same presuppositions of those French progressivist movements. They wrongly sustained that the Church was the cause of the workers’ crisis. Then they came with a false solution: since all men are equal regarding property, all should have just that minimal amount of property which would not generate ambition. This they presented as an “original” solution: a Third Position between Capitalism and Communism. Undoubtedly, this solution is clearly against Capitalism, but it is not at all clearly against Communism. I don’t know whether it is an explicitly pro-communist doctrine or, as some sustain, a variant of Socialism similar to Nazism and Fascism.

Gill’s attack against the old liturgy

Eric Gill’s “originality” in proposing this solution regarding the workers’ crisis had a parallel development in the progressivist liturgical movements that were appearing simultaneously in France and Germany. They sustained that one of the causes that made workers abandon the Faith was supposedly the perennial liturgy of the Church that didn’t attract the masses. Gill thought that it alienated the simple people from worship.

Above, a 1922 wood-engraving, Crucifixion, picturing a nude Christ. Below, another Christ drawn in 1918

|

He stated:

“We use a language [Latin] which is not understood and the visitor to our churches sees us doing all sorts of strange things dressed up in strange garments which have no resemblance to any in the world he inhabits.” (p.7)

He continues:

“For one reason or another, the Church does not seem to them to offer an acceptable solution to their problems, whether in the sphere of morals, or of philosophy or of politics.” (p.7)

Just like modern-day adherents of Progressivism, Gill believed that the masses saw a contradiction between the message of the Gospel and the beautiful vestments, splendorous architecture, and rich ceremonies of the Church:

“And when it comes to politics he [the common man] seems to find a state of contradiction. On the one hand is the religion of Christianity as he understands it from the Gospels, the religion of God made man, the poor man, the common man, the working man, and on the other the curiously ornate churches, the elaborate ceremonies – vast and grand places in which one is as afraid to walk as in Buckingham Palace, with guards and soldiery and a display of worldly grandeur as great as that of any Mansion House or Royal Academy, all of which seems to display an alliance between the Church and the very Mammon condemned in the gospels.” (p.7)

According to Gill, the beauty of the churches of the 1930’s was not the product of devout Christians presenting their best efforts and fruits to God. Rather, these churches were like everything else in the world, “stuff produced solely for the profit of the investors of capital.” He states:

“For it is not as if our churches were the holy products of practicing Christians; they are, for the most part, like everything else in our world, the product of our industrial commercial system, machine-made mass products, imitation antique, whether Gothic or Classic, in fact not made by man but simply merchandise – stuff produced solely for the profit of investors of capital.” (p.7)

When I read the next statement, I had to remind myself that this was written back in 1938; it sounds just like the progressivist talk we hear today from the supporters of Vatican II. According to Gill, worship of God had become an elaborate ritual of an increasingly professional priesthood; an obedience to an elaborate code of rules and regulations that he offensively referred to as "pharisaism" and a bondage to dead formalism. He affirmed:

“Let us go back to the beginning. What is Christianity? Christianity is the following of Christ, the religion of Christ, Christ the Son of God, God Himself incarnate… The worship of God invisible, mysterious and aloof, known only through His prophets, the centre of human worship, adoration and praise but also inevitably the centre of fear – a jealous God – became in the course of time the centre of an elaborate ritual and worship ministered by a priesthood more and more professional, so that the religion of Jehovah became to a large extent a matter of obedience to an elaborate code of rules and regulations. It is not necessary to enlarge upon this. The problem of pharisaism is always with us.

“Whatever else we may say or think, the Incarnation means the release of man from the thralldom of dead formalism, it means God known by sight –‘For as we know God by sight…’ – no longer simply the awful Father but also Brother and Friend – the religion of love and not simply of propitiation. Here then is a vital and tremendous distinction. God is among men, surrounded by them. He lives and talks among them as one of themselves.” (p. 8)

A proposal for liturgical reform

Gill, much like a present-day progressivist, said that the Church should be reformed immediately:

“From time to time there is a need for rejuvenation; and such a time is now.” Shortly after he added: “these facts make it necessary to reconsider the nature of the liturgy, that is to say, public prayer and worship.” (p.8)

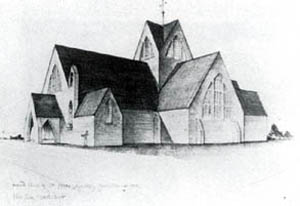

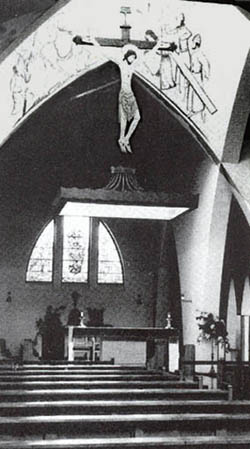

The church of St. Peter the Apostle at Gorleston-on-Sea, Norfolk, a modernist project by Gill completed in 1939 The church of St. Peter the Apostle at Gorleston-on-Sea, Norfolk, a modernist project by Gill completed in 1939 |

Gill detested the fact that the churches had grown larger and larger, and the altars more elaborate and splendorous. All of these developments of Christian liturgy supposedly had served to separate the people from God. According to him, this process had to be reversed:

“This is not a historical dissertation. It is no business of mine to describe how Christian ritual has developed, to describe how churches grew longer and longer and how altars became more and more elaborate and withdrawn from the people. The thing happened. The question for us is not how or why, but what we are going to do about it. It seems clear that just as Christianity itself must become again the religion of the people, the common people, the masses, so Christian worship must follow suit. There must be some physical sign of the rejuvenation which is necessary.” (p.9)

The specific reforms demanded by Gill

- Move the altar

Just like today’s progressivists, Gill insisted that the altar should be placed in the center of the Church surrounded by the people:

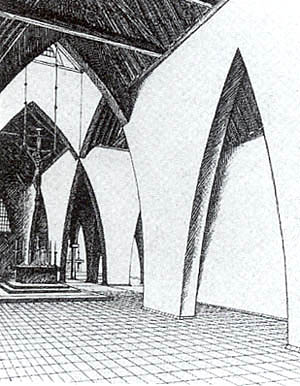

A sketch of the interior of the Church of St. Peter shows the altar brought down to the level of the people |

“There is one thing which must be done, and it must be done immediately; for the time is short. But it is a very big thing as well as a very simple one. It is a very revolutionary thing…The altar must be brought back again into the middle of our churches, in the middle of the congregation, surrounded by the people – and the word surrounded must be taken literally. It is essential that the people should be on all sides, in front and behind. The Holy Sacrifice must be offered thus, and in relation to this reform nothing else matters.” (p.9)

He affirmed that any separation between the altar and the people – such as communion rails, the priest’s seats, etc. – was monstrous:

“At the present time it is the custom to place the altar at the end of the church, very often in a specially built apse or chancel and generally separated from the people by the seats of the ministers…. There is thus a monstrous division between the place of the altar and the rest of the church. The sanctuary is ruled off as being not merely a holy place but a mysterious place – a place in which only professional feet may tread [priests, clergy, etc.], a place in which the laity can only enter, more or less timidly, when they go up to receive the Communion.” (p.9)

– Move the Altar even in existing churches

He advocated that these reforms must be made not only on all future churches built, but all the existing churches as well:

“Even in the existing buildings the same thing might be done and must be done. Bring the altar down to the middle. Fill up the “sanctuary” with seats; wherever the altar is, there is the sanctuary, but as God came among men, so must the altar be.” (p.10)

Gill was not concerned about violating the beauty of traditional Cathedrals and “our more or less quaint customs.” He believed such things were of no importance compared to the urgent need for immediate changes - the very same changes that were imposed on all Catholics after Vatican II.

“It will, of course, be said that this suggestion will violate all the architectural arrangements, as well as affront our ancient customs. But architectural and our more or less quaint customs are of no importance compared with the vital necessity of our time. Some will say that the altar will not look nice where we suggest putting it; that is not the question. The only question is where it would be right.” (p.10)

– “Away with” the choir, organ, vestments and all that “frippery”

Like his fellow progessivists at Vatican II, Gill thought that all the beauty of the Church and her liturgy was useless and must be done away with. According to Gill, if we are too weak and “feeble” to get rid of these treasures, we should at least ignore them:

“The choir and the organ, the vestments and the stained glass windows, the carvings, the paintings and the statues, all are so much frippery compared with the altar and the service of the altar. And it is inevitable that such things should be, in literal fact, little better than frippery today. They are not the product of the people’s hands. They are for the most part mere merchandise, stuff produced like everything else not for any use, holy or unholy, but for profit. Away with them - if that be too difficult for our feebleness, at least let us disregard them; for merely to remove frippery, to wallow in an orgy of good taste is not itself of any value at all.”(p.9)

– Away with “medievalism” and “medieval customs”

Distributists constantly present to Catholics the idea that they are trying to revive Christendom. They build socialist worker communes and call them guilds, as if their self-management socialist groups have anything to do with medieval guilds. But Eric Gill, a founder of Distributism, said the exact opposite concerning the Middle Ages. Gill viewed medieval customs and medievalism as an obstacle to the Church’s revival:

“The liturgy must be revived, revived, i.e., made alive again. But ‘to revive the liturgy it is first necessary to disinter it.’ It is buried at present beneath a load of medieval and post-medieval custom.” (p.9)

He added:

“Will this cause scandal?…What do you want? Do you want a continuance of an obscure medievalism? Do you pin your faith to a mere revival of medieval music?” (p.10)

Gill’s outlook on the future liturgy

Gill’s description of what he envisioned for the future concerning liturgy is truly prophetic of what came after Vatican II: No “frippery;” nothing of the beauty, splendor, dignity, hierarchy, ceremony, or grandeur of a bygone era. He imagined a future church like this:

“It is necessary perhaps to have some imagination in considering this matter. Figure yourselves, then, entering a church where this reform has been made. Forget the architecture, forget the things associated with ecclesiastical buildings. You see, shall we suppose, a plain building, and in the apparent centre of it, whatever its actual geometrical shape, slightly raised so that it may be visible to all, the altar with crucifix above or upon it. The people are on all sides, the Mass proceeds, whether in Latin or in English or any other language. Everybody can see what is being done…There is no choir or organ business to distract them, no imitation Gothic windows, no frippery of any kind” (p.10)

Gill affirmed that if the altar is brought down to the people, then the liturgy, and especially receiving Communion, will become a clamorous act of the people. In other words, it will be reduced to an egalitarian demand of the mob, a type of Pentecostal revival in a plain, miserablist environment. (2) He stated:

The interior of St. Peter the Apostle around 1970. From his architectural perspectives, Gill was a precursor to Vatican II |

“And another extremely important thing effected by this placing of the altar [in the center of the church] is the emphasis placed on the act of receiving Communion. This act will remain all it is at present but it will become more. It will become corporate, a public act. It may be imagined to become even a clamorous act. It will become the act of the people clamouring for Bread – demanding recognition as the Mystical Body of Christ.” (p.10)

Soon after, he added:

“All these things are figured by the altar – the altar not at which something is done, something seen at the end of a vista; but the altar on which something is offered and offered in the midst of our acclamation …” (p.10)

Eric Gill was not just a revolutionary liturgical reformer in theory. His one and only architectural work was the design and construction of a church, St. Peter the Apostle at Gorleston-on-Sea, Norfolk. He used all his “powers of persuasion on the slightly nervous Father Thomas Walker, telling him that by agreeing to Gill’s schemes for the centralization of the altar he will be taking part in ‘a great movement for the re-evangelization of the people.’” (3)

It was the second church built in England (1939) where the altar was placed in the center. The first such church was constructed by Gill’s confidant and fellow reformer, Fr. John O’Connor (see: Other Moral “Pearls” of Eric Gill).

Gill’s church was designed following the rules of what he called “Plain Architecture.” To quote him, these reforms would eliminate all the “mystery mongering of obscure sanctuaries separated from the people.” (4) Fiona MacCarthy and Michael Yorke, authors of respected biographies on Gill, both affirm that many of the questions raised by Gill were resolved with the coming of Vatican II.

Link between liturgical reform & the back to the land movement

The Distributist founder makes an interesting comparison of ideas. He compared the liturgical reforms he proposed to the “back to the land” movement. According to him, both are trying to bring power and control back to the people:

“The only important thing and the only thing that matters is to bring the altar to the people. Its is like the cry “back to the land” which means back to the people, back to humanity and in this connection we must add, back to Christianity, back to the Incarnation.” (p.10)

The sin of pride creates an egalitarian mentality that hates any inequalities. Just as Gill’s Distributism hates the division between intellectual and manual labor, the existence of different classes, and the inequalities between the employee and employer, so also does Gill hate the division between the people and the clergy, or even any division between the people and God. He declared:

“The divorce between the clergy and the people, between the people and the altar, has become as wide as the distinction between the artist and the factory hand, the responsible human worker on the one hand and the irresponsible tool on the other.” (p.9)

Gill’s hatred for the rich as such is well summarized in this statement:

“He [Christ] came not to make the poor rich and the rich richer, but to make the rich poor … and the poor holy.” (p.10)

The conclusion to this article is both solid and clear: Eric Gill, a founder of Distributism, was a progressivist and a precursor of Vatican II.

Final questions

After analyzing Gill’s progressivist ideas, one is faced with a reality that is, in some sense, bizarre and contradictory. Why are some Traditionalists promoting this kind of Progressivism? Why are movements that defend the Tridentine Mass and the traditional liturgy spreading the ideas of a man who is adamantly against both?

I lack sufficient information to objectively answer these questions; nevertheless, I think it is useful to keep them in mind.

1. Eric Gill , Mass for the Masses, published in The Cross and the Plough: The Organ of the Catholic Land Associations of England and Wales, 1938, vol. 4.

2. Miserablist Church: a Church that should be turned exclusively toward the poor. It takes as its model Judas Iscariot who proposed that Our Lord should have sold the perfume Mary Magdalene poured on His feet and give the money to the poor. On this topic, listen to the tape – The Miserablist Church, by Atila S. Guimarães.

3. Fiona MacCarthy, Eric Gill (Faber & Faber, 1989), p.280

4. Ibid.; Michael Yorke, Eric Gill: Man of Flesh and Spirit (London & New York: Tauris Parke Paperbacks, 1981) p. 235.

Posted July 15, 2005

Related Topics of Interest

Eric Gill: the Pedophile Founder of Distributism Eric Gill: the Pedophile Founder of Distributism

Other Moral Pearls of Eric Gill Other Moral Pearls of Eric Gill

Pros & Cons on Eric Gill, a Founder of Distributism Pros & Cons on Eric Gill, a Founder of Distributism

A Distributist Manifesto Strongly Spiced With Communism A Distributist Manifesto Strongly Spiced With Communism

Socialism and Distributism in Catholic Clothing Socialism and Distributism in Catholic Clothing

|

Social-Political | Hot Topics | Home | Books | CDs | Search | Contact Us | Donate

© 2002- Tradition in Action, Inc. All Rights

Reserved

|

|

|