American History

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mary of Agreda in America - Part VI

Did Ven. Mary of Agreda Bilocate to California?

It is well known that Ven. Mary of Jesus of Ágreda (1601-1665) bilocated more than 500 times between the years to 1620 to 1631 visiting Indians in New Mexico, Arizona and Texas. The Conceptionist nun with her distinctive sky blue cape, who never left her Convent in Spain where she was Abbess, has come down to us in History as the “Lady in Blue,” as the Indians called her. (1)

But did Ven. Mary of Agreda ever visit California? That was a question a good friend posed to me on our recent pilgrimage to visit Our Lady of Bethlehem in Mission San Carlos Borromeo in beautiful Carmel-on-the-Sea, California.

But did Ven. Mary of Agreda ever visit California? That was a question a good friend posed to me on our recent pilgrimage to visit Our Lady of Bethlehem in Mission San Carlos Borromeo in beautiful Carmel-on-the-Sea, California.

Upon our return from the pilgrimage, I delved into study and found two amazing legends that could allow one to affirm that there were, indeed, bilocations of Franciscans to California that prepared the Indians here for the grand work of Fr. Junípero Serra (1713-1784), who established the first nine missions of Alta California in those fecund last 15 years of his life. (2)

The first was recorded by his missionary companion Fr. Francisco Palou in the monumental biography he wrote shortly after Fr. Serra’s death. In it, he relates the story of the old Indian woman Agueda, who told the first missionaries of San Antonio de Padua that two men dressed like Franciscans had come from the skies to visit the Indians in the days of her father. (3)

The second legend, recorded by historian Frances Rand Smith in her narrative on the Mission of Santa Cruz (4) touches more directly on our topic since it could well place Mother Maria de Agreda herself in northern California.

Fr. Serra peals the bells on an oak tree

It was the year 1771, one year after the founding of Mission San Carlos Borromeo in Monterey. Fr. Serra, Fr. Buenaventura Sitjar, Fr. Miguel Pieras and a small expedition of soldiers, sailors and native Indians set out to establish the site for Mission San Antonio de Padua.

After examining the area, they determined that the third Mission should be raised for the glory of God and Spain on a plain in a valley adjoining a river, which they named the San Antonio.

No sooner had the site been chosen than Fr. Serra commanded that the church bells destined for that mission should be unloaded and hung from a nearby oak tree. Then Fr. Serra himself shouted out to the empty plain: “Come, you pagans, come! Come to the Holy Church! Come, come to receive the Faith of Jesus Christ!”

No sooner had the site been chosen than Fr. Serra commanded that the church bells destined for that mission should be unloaded and hung from a nearby oak tree. Then Fr. Serra himself shouted out to the empty plain: “Come, you pagans, come! Come to the Holy Church! Come, come to receive the Faith of Jesus Christ!”

Seeing this spectacle, Fray Miguel Pieras, asked him why he tired himself out so since the church was not yet to be built nor was a single pagan anywhere in sight. “It is a waste of time,” he noted. Fray Junípero replied, “Father, allow my overflowing heart to express itself. Would that this bell were heard throughout the world, as the Ven. Sor Maria de Ágreda desired, or at least that it were heard by every pagan who inhabits this sierra.” (5)

After this they constructed, blessed and raised a large cross on that very spot. On a makeshift altar the first Mass in honor of St. Anthony, the Mission’s patron, was said on that July 14, the feast of the Seraphic Doctor St. Bonaventure.

As if in response to the call of the bells, one pagan appeared and remained present throughout the Mass. Fr. Serra noted this triumph in his sermon: “Here we behold what was not seen at any mission so far founded: that at the first Mass the first fruits of paganism were present. Nor will he fail to communicate to the other pagans what he has seen here.”

As if in response to the call of the bells, one pagan appeared and remained present throughout the Mass. Fr. Serra noted this triumph in his sermon: “Here we behold what was not seen at any mission so far founded: that at the first Mass the first fruits of paganism were present. Nor will he fail to communicate to the other pagans what he has seen here.”

And, indeed, so it happened. That very day many other Indians from the area approached the friars, showing them signs of esteem and making gifts of pine nuts and acorns along with other wild seeds.

The old Indian woman Agueda

What was the cause of this welcome and confidence shown? Later, after the friars had learned the language, they began to catechize and baptize the Indians. Among those first neophytes was a woman named Agueda. She was “so ancient that in appearance she seemed to be about 100 years old,” Fray Palou relates. (6)

She came and directly asked the fathers to baptize her. Surprised, they asked her why she wanted to be a Christian. She told them that when she was very young her parents told of a man who came to their lands dressed in the same habit that the missionaries wore. But “he did not walk through the land, but flew.” (7)

He told them the same things the missionaries were now preaching, she said. Remembering this, she felt a great desire to become a Christian.

He told them the same things the missionaries were now preaching, she said. Remembering this, she felt a great desire to become a Christian.

Unwilling to give credence to the single testimony of an old woman, the friars made inquiries among the other neophytes of area. Unanimously they affirmed that this was exactly what their ancestors had told them, and that it was handed down as a tradition among them.

When Fr. Palou heard this story from the fathers, he immediately remembered a Letter written in 1631 by Mother Mary of Agreda to the Franciscan Missionaries who had begun the spiritual conquest of New Mexico. In it, she affirms that at that very time, their holy Father, St. Francis, had sent to these nations of the north two holy men of the Order to preach the Faith of Jesus Christ, and that after having made many converts they suffered martyrdom.

“On estimating the time when they made their visit,” Palou writes, “I concluded It might have been one of these holy men of whom the convert Agueda had spoken.” (8)

Who was this Franciscan who came to the Indians in this region along the San Antonio River in California’s Valley of the Oaks in present-day Monterey County? The question still has no answer.

However, the oral history of the native Indians clearly points to the existence of a “flying” friar who visited their area and prepared the way for the peaceful welcome of Fr. Serra’s friars 142 years after Ven. Mary of Agreda penned her historic Letter. Certainly the time span before his appearance could cover the two generations of Agueda and her father, given the old age of the daughter.

One can ask if it is a “coincidence” that the old woman’s name was Agueda, which so closely resembles Agreda, a town in Spain on the borders of Navarre and Aragon? The missionaries would have realized the similarity of two names, and perhaps surmised that the flying friar came from a monastery in the town of Ven. Mary of Jesus.

The teaching Madre at Mission Santa Cruz

In the early 20th century, historian Frances Rand Smith heard about the old Indian woman Agueda and became curious if there were any other bilocation stories among the Missions of California.

In the early 20th century, historian Frances Rand Smith heard about the old Indian woman Agueda and became curious if there were any other bilocation stories among the Missions of California.

She found that a similar story had been passed from generation to generation among the Indians of Mission Santa Cruz, the 12th California Mission founded in central Californian coast in 1791 by Fr. Fermin de Lasuén, the successor of Fr. Junipero Serra. There was one significant difference, however: The Franciscan missionary who had appeared there among the Indians to instruct them was a woman.

A letter written by Fr. Juan B. Comellas, who was prebyster at the restored Santa Cruz Mission church from 1854 to 1856, relates an early legend about a flying nun that he copied from a book in the archives of that Mission. (9)

The document notes that the Indians of the region had preserved the tradition from their forefathers that at in the past a woman from a far off country had come to their region. An old Indian of Santa Cruz said that she was called “the Padre with the Mamas,” because she appeared to them dressed as a Padre but was clearly a woman with a feminine bosom.

The document notes that the Indians of the region had preserved the tradition from their forefathers that at in the past a woman from a far off country had come to their region. An old Indian of Santa Cruz said that she was called “the Padre with the Mamas,” because she appeared to them dressed as a Padre but was clearly a woman with a feminine bosom.

She preached to the Indians and told them that within a short time white men would come to them to show them the way to Heaven and help them to leave their state of darkness and ignorance.

This Franciscan Madre told them they ought not to fear these men for they would do them no harm, and that they should believe what the fathers would tell them. That tradition, the old Indian continued, contributed to incline his forefathers to accept the preaching of the Friars and to embrace Christianity without repugnance.

Fr. Comellas continues: “We do believe that said woman was the Venerable Mother Maria de Jesús Ágreda.” (10)

It is a rich nugget of history from the past that opens the door to the real possibility that Mother Mary of Agreda made bilocations to California and prepared the Indians here for the day when the Friars would come.

Continued

Continued

Our Lady of Bethlehem, a life-size statue that came with Fr. Serra to California in 1769

Upon our return from the pilgrimage, I delved into study and found two amazing legends that could allow one to affirm that there were, indeed, bilocations of Franciscans to California that prepared the Indians here for the grand work of Fr. Junípero Serra (1713-1784), who established the first nine missions of Alta California in those fecund last 15 years of his life. (2)

The first was recorded by his missionary companion Fr. Francisco Palou in the monumental biography he wrote shortly after Fr. Serra’s death. In it, he relates the story of the old Indian woman Agueda, who told the first missionaries of San Antonio de Padua that two men dressed like Franciscans had come from the skies to visit the Indians in the days of her father. (3)

The second legend, recorded by historian Frances Rand Smith in her narrative on the Mission of Santa Cruz (4) touches more directly on our topic since it could well place Mother Maria de Agreda herself in northern California.

Fr. Serra peals the bells on an oak tree

It was the year 1771, one year after the founding of Mission San Carlos Borromeo in Monterey. Fr. Serra, Fr. Buenaventura Sitjar, Fr. Miguel Pieras and a small expedition of soldiers, sailors and native Indians set out to establish the site for Mission San Antonio de Padua.

After examining the area, they determined that the third Mission should be raised for the glory of God and Spain on a plain in a valley adjoining a river, which they named the San Antonio.

The distinctive oaks in the Valley of the Oaks

in Central California

Seeing this spectacle, Fray Miguel Pieras, asked him why he tired himself out so since the church was not yet to be built nor was a single pagan anywhere in sight. “It is a waste of time,” he noted. Fray Junípero replied, “Father, allow my overflowing heart to express itself. Would that this bell were heard throughout the world, as the Ven. Sor Maria de Ágreda desired, or at least that it were heard by every pagan who inhabits this sierra.” (5)

After this they constructed, blessed and raised a large cross on that very spot. On a makeshift altar the first Mass in honor of St. Anthony, the Mission’s patron, was said on that July 14, the feast of the Seraphic Doctor St. Bonaventure.

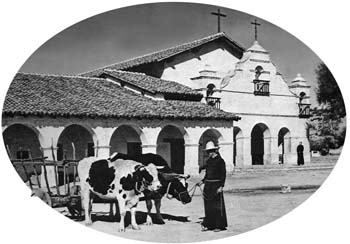

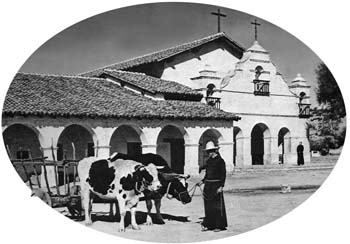

Fr. Serra stands in front of Mission San Antonio, the third mission he founded

And, indeed, so it happened. That very day many other Indians from the area approached the friars, showing them signs of esteem and making gifts of pine nuts and acorns along with other wild seeds.

The old Indian woman Agueda

What was the cause of this welcome and confidence shown? Later, after the friars had learned the language, they began to catechize and baptize the Indians. Among those first neophytes was a woman named Agueda. She was “so ancient that in appearance she seemed to be about 100 years old,” Fray Palou relates. (6)

She came and directly asked the fathers to baptize her. Surprised, they asked her why she wanted to be a Christian. She told them that when she was very young her parents told of a man who came to their lands dressed in the same habit that the missionaries wore. But “he did not walk through the land, but flew.” (7)

A Franciscan friar came to them but ‘he did not walk through the land, but flew’

Unwilling to give credence to the single testimony of an old woman, the friars made inquiries among the other neophytes of area. Unanimously they affirmed that this was exactly what their ancestors had told them, and that it was handed down as a tradition among them.

When Fr. Palou heard this story from the fathers, he immediately remembered a Letter written in 1631 by Mother Mary of Agreda to the Franciscan Missionaries who had begun the spiritual conquest of New Mexico. In it, she affirms that at that very time, their holy Father, St. Francis, had sent to these nations of the north two holy men of the Order to preach the Faith of Jesus Christ, and that after having made many converts they suffered martyrdom.

“On estimating the time when they made their visit,” Palou writes, “I concluded It might have been one of these holy men of whom the convert Agueda had spoken.” (8)

Who was this Franciscan who came to the Indians in this region along the San Antonio River in California’s Valley of the Oaks in present-day Monterey County? The question still has no answer.

However, the oral history of the native Indians clearly points to the existence of a “flying” friar who visited their area and prepared the way for the peaceful welcome of Fr. Serra’s friars 142 years after Ven. Mary of Agreda penned her historic Letter. Certainly the time span before his appearance could cover the two generations of Agueda and her father, given the old age of the daughter.

One can ask if it is a “coincidence” that the old woman’s name was Agueda, which so closely resembles Agreda, a town in Spain on the borders of Navarre and Aragon? The missionaries would have realized the similarity of two names, and perhaps surmised that the flying friar came from a monastery in the town of Ven. Mary of Jesus.

The teaching Madre at Mission Santa Cruz

Mission Santa Cruz, the 12th California Mission

She found that a similar story had been passed from generation to generation among the Indians of Mission Santa Cruz, the 12th California Mission founded in central Californian coast in 1791 by Fr. Fermin de Lasuén, the successor of Fr. Junipero Serra. There was one significant difference, however: The Franciscan missionary who had appeared there among the Indians to instruct them was a woman.

A letter written by Fr. Juan B. Comellas, who was prebyster at the restored Santa Cruz Mission church from 1854 to 1856, relates an early legend about a flying nun that he copied from a book in the archives of that Mission. (9)

The ‘Madre’ missionary: Was she Ven. Mary of Agreda?

She preached to the Indians and told them that within a short time white men would come to them to show them the way to Heaven and help them to leave their state of darkness and ignorance.

This Franciscan Madre told them they ought not to fear these men for they would do them no harm, and that they should believe what the fathers would tell them. That tradition, the old Indian continued, contributed to incline his forefathers to accept the preaching of the Friars and to embrace Christianity without repugnance.

Fr. Comellas continues: “We do believe that said woman was the Venerable Mother Maria de Jesús Ágreda.” (10)

It is a rich nugget of history from the past that opens the door to the real possibility that Mother Mary of Agreda made bilocations to California and prepared the Indians here for the day when the Friars would come.

A friar in the early days of Mission San Antonio

- These bilocations are not legends: The case has been well studied, documented and confirmed by Church authorities in both the time of Ven. Mary of Agreda and afterwards. Margaret Galitzin, Ven. Mary of Agreda in America, TIA, 2011, p. 24.

- The missions established under the Presidency of Fr. Serra were San Diego de Alcalá (1769), San Carlos Borromeo (1770), San Antonio de Padua (1771), San Gabriel Arcángel (1771), San Luis Obispo de Tolosa (1772), San Francisco de Asis (1776), San Juan Capistrano (1776), Santa Clara de Asis (1777), and San Buenaventura (1782). He was also present at the founding of the Presidio of Santa Barbara (1782).

- Palou’s Life of Fray Junípero Serra, trans. By Maynard J, Geiger, OFM, Washington DC: Academy of American Franciscaqn History, 1955.

- “Early Indian Legend” in The Mission of San Antonio de Padua, Stanford, London: 1932, pp. 82-99.

- Palou’s Life of Fray Junípero Serra, p. 110-111.

- Ibid. p.112.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 113.

- From an article by Alexander S. Taylor titled “The Indianology of California,” in Rand, The Mission of San Antonio de Padua, p. 87

- Ibid.

Posted June 8, 2024

______________________

______________________