|

Book Reviews

Jewish Scholar Exposes

Ritual Crimes by His Ashkenazy Fellows

Atila S. Guimarães

Book review of Pasque di sangue Ebrei d'Europa e omicidi rituali [Bloody Passovers European Jewish & Ritual Homicides], by Ariel Toaff, Bologna: Il Mulino, 2007, Online edition, 242 pp.

Bloody Passovers refers to the ritual crucifixions of Catholic boys and the consumption of their blood by Ashkenazy Jews at Passover celebrations. These ceremonies reportedly took place at least up to 15th century.

This controversial book written by Prof. Ariel Toaff (A.T.), an Italian Jewish scholar, raised indignation as soon as it was published in 2007. Toaff is the son of Elio Toaff, former chief rabbi of Rome and the partner of John Paul II in countless inter-religious ceremonies. Although this Jewish scholar seems to represent a considerable part of Italian Judaism, his liberal Jewish supporters were not strong enough to keep his book in circulation. Other currents of Judaism considered his work to be gravely inconvenient, and imposed a de facto embargo on its distribution shortly after its release.

Nonetheless, Società Editrice Il Mulino managed to keep an online edition in the public domain available to be downloaded and printed. It numbers 242 pages, sized for 8 ½” x 11” paper, a format different from the original published work of 346 pages. I am basing my review on the Italian online edition by Il Mulino, which can be found here. I did not read or compare the Italian text with its anonymous English translation, which can be found here.

I - Author, thesis & method

Ariel Toaff is professor of Medieval and Renaissance History at Bar Ilan University in Tel Aviv. In this work, he reveals a remarkable capacity for research and the reconstitution of historical situations, especially regarding persons involved in religious-economic criminal intrigues. So many people are involved in those intricate actions that, to follow them and evaluate Toaff’s arguments, I felt the need to make my own person index as I read. I suspect other readers have felt the same need, since Il Molino later added a name index to its online edition.

Ariel Toaff, author of Bloody Passovers

|

Toaff bases his work on an imposing number of both Jewish and Catholic primary sources, which reflects a respectfully sizeable work of searching, finding, reading and classifying before writing.

His most notable quality, however, is the courage he shows to face the ensemble of Jewish scholars who have tried to present the conclusions of past Catholic tribunals that condemned Jews as non-objective. Toaff attributes the general line of these scholars’ works to the biased and preconceived conclusion that the Jews had to be innocent of every accusation. On the other hand, he criticizes those Catholic authors who pretend exactly the opposite. What he tries to do is to situate himself as an impartial viewer of the facts.

His whole theme sails in the waters of Criminal Law, that is, it asks to what measure and for what reasons the charges against Jews regarding ritual homicides issued by Catholic tribunals were true.

To the basic criminal discussion on this topic, he adds his robust erudition on Jewish liturgical practices as well as knowledge of religious documents written in Hebrew or Yiddish. This contribution alone makes his work a reference point for any future serious study.

The thesis of the book is clear: The ritual homicides of Catholic children existed and were practiced by Jews of the Ashkenazy observance.

The thread linking the chapters could certainly be improved if one is viewing the book from a Western scholarly perspective. I would say that the weak point of this book is that Toaff pretends to present his serious thesis as a captivating police drama. I believe he did not achieve this goal, and this intent harmed the clarity of his exposition. This is a heavy and hard-to-read book due both to its macabre subject and the twisted path often adopted.

Toaff exposes the theme in Solomonic style, like a spiral column

|

I would say that the thesis is proved on a road that rises spirally along the 15 chapters, not a usual method employed in Western scholarly expositions, but not rare in Jewish literature. It is called the Salomonic or Babylonian style, referring to the columns with twisted fluting in furniture and architecture or to the contorted language employed by the rabbis who wrote the Talmud of Babylon.

Toaff’s method of demonstration is dialectical: He first seems to agree with those who deny ritual homicides; then he presents historical evidences refuting that argument. The conclusions are not always transparent, which invites the reader to wonder whether Toaff feared counter-attacks were he as conclusive as he should and could have been.

His personal position in demonstrating his thesis is also curious. He pretends to be superior to both the Ashkenazy Jews and the Catholics involved in the criminal scenario. But, instead of criticizing them, as one would expect, he often disdainfully impersonates them as if he believes in what they say. So, we frequently find Toaff with his sardonic and blasé smile repeating the praises that both religions – the Jewish and the Catholic - make of themselves, without offering his own critique.

II - Reviewing the subject matter

Given these particular characteristics of Ariel Toaff’s style, I believe that the best way to make the content of his work accessible to my reader is to make a logical analysis of it according to our Catholic Scholastic method.

I will bring to light the original points of his argument and show how they change the panorama, forcing the reader to reconsider the constant, obsessive and often virulent Jewish denial of those crimes sentenced by Catholic tribunals of the past.

Although I will strictly keep to the text, I will not follow the order of the chapters.

Given the importance of the thesis, sometimes I will not summarize, but will transcribe the actual words of the text between quotations. This will cause the inconvenience of making this review much longer than normal, but it will provide the reader with the proofs needed to use for the defense of the Catholic cause.

1. The mentioned ritual homicides

Sprinkled throughout his book, A.T. refers, extensively or briefly, to the following 67 alleged ritual homicides of Catholic children by Jews, which I am ordering here by country and date:

Italy

1451 Candia (pp. 41, 43, 45)

1451 Trent (p. 65)

1456 Savona (pp. 66, 127)

1469 Padua (pp. 64, 76)

1472-1475 Trent (pp. 12, 51, 52, 64, 174)

1479 Arena (p. 57)

1480 Portobuffalè (pp. 54, 55)

1481 Cremona (p. 56)

1482 Tortona (pp. 55, 56, 78)

1485 Valrovina (pp. 59, 60)

No date: Mestre (p. 64);

Piedmont (p. 64); Pavia (p. 66)

Germany & Austria

1147 Würzburg (p. 98)

1187 Mainz (p. 101)

1195 Speyer (p. 101)

1197 Neuss (p. 102)

1199 Cologne (p. 101)

1235 Fulda (p. 102)

1261 Pforzheim (pp. 68, 69, 97, 103)

1283 Bacharach (pp. 103, 105)

1283 Mainz (p. 103)

1285 Munich (p. 104)

1293 Krems (p. 104)

1303 Weissensee (p. 105)

1332 Überlingen (p. 104)

1345 Munich (p. 104)

1429 Ravensburg (p. 105)

1429 Oberwesel (p. 105)

1440 Landshut (p. 70)

1442 Lienz (p. 104)

1460 Worms (pp. 62, 63, 68)

1461 Gunzenhausen (p. 63)

1462 Rinn (p. 61)

1462-1470 Endingen (pp. 67, 68, 69)

1465 Nuremberg (pp. 68)

1466 Bayreuth (p. 63)

1467 Regensburg (pp. 70, 72, 87, 174)

1504 Waldkirch (p. 93

|

Switzerland

1294 Bern (p. 105)

1329 Geneva (p. 126)

1329 Annecy (p. 126)

England

1144-1146 Norwich (pp. 7, 95-98, 102)

1160-1168 Gloucester (p. 99)

1181 Bury (p. 99)

1183 Bristol (p. 99)

1193 Winchester (p. 99)

1244 London (p. 99)

1255 Lincoln (pp. 99, 100)

1279 Northampton (p. 103)

1463 Wending (p. 63)

No date: Canterbury (p. 100)

Hungary

1494 Tyrnaau (pp. 82-88)

1520 Posing (p. 88)

France

1171 Blois (p. 100)

1179 Joinville (p. 100)

1179 Pointoise (p. 100)

1191 Brie (p. 115)

1247 Valréas (p. 97)

1288 Troyes (p. 103)

1329 Rumilly (p. 126)

1453 Arles (p. 127)

1458 Chambery (p. 105)

Spain

1456 Valladolid (p. 66)

Bohemia

1305 Prague (p. 104)

Syria

415 Inmestar (pp. 114, 115)

|

Although the author does not admit that each one of these alleged ritual murders of Catholic children by Jews actually happened, he affirms that some of them did. I believe this acknowledgement is enough to break the fabrication that they never occurred.

Indeed, when Toaff discusses details of the trials of Trent, Pforzheim, Regensburg and Norwich, the reader is led to the inevitable conclusion that those ritual crimes really were committed.

2. Evidence of the veracity of the Trent reports

There is much evidence that the accusations of the Catholic Tribunal of Trent (1472-1475), which analyzed the murder of St. Simon by important Jews of the city, were objective. (1)

A. The judges could not have invented the details

Toaff affirms: “The trial record, particularly the minutely detailed reports relating to the death of the little Simon of Trent, cannot be dismissed on the assumption that such records would only mirror the beliefs of the judges, who would have collected confessions dictated and manipulated by coercive means in order to ensure that they conformed to the anti-Jewish theories circulating at that time.

“Indeed, a careful reading of the trial records, in both form and substance, reveals there are too many elements that correspond to the conceptual realities, rituals, liturgical practices and mental attitudes typical of an exclusive, particular Jewish world – elements that can in no way be attributed to suggestions on the part of the judges and prelates – to be ignored.” (p. 6, see also pp. 140, 141)

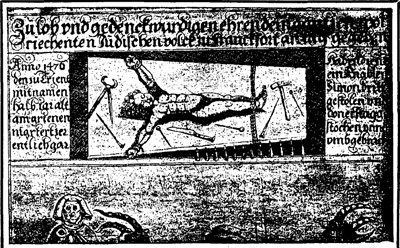

St. Simon of Trent, ritually murdered by the Jews, a bas-relief by Francesco Oradini

|

Still on the topic of Trent, Toaff says: “In many cases, what the accused said was incomprehensible to the judges, often because their speech was filled with ritual and liturgical Jewish formulae pronounced with a heavy German accent, unique to their own world, which not even the Italian Jews could understand; in other cases, because their confessions referred to legal concepts of a particular mind frame and an ideological language completely foreign to everything Christian.

“It is obvious that neither the formulae nor the language can be dismissed as merely the shrewd fabrications and artificial suggestions of the judges in these trials. To delegitimize them by presenting them as the inventions and extemporaneous creations of the defendants terrorized by torture and made only to satisfy the demands of their inquisitors, cannot be accepted as a prerequisite for the present study.” (p. 9).

Further on, A.T. affirms: “In substance, the so-called ‘confessions’ of the accused in the Trent trials relating to the rituals of the Passover Seder [preparation] and Haggadah [text and liturgy] reveal themselves to be truthful and precise. … The Jews of Trent, in describing the Seder in which they had participated, were not lying nor were they following suggestions of the judges, who were presumably ignorant of a large part of the ritual being described to them” (p. 144; see also pp. 150, 165, 168)

I believe these arguments are fully conclusive and exonerate the judges of Trent from the accusation of falsification, leading to the conclusion that its sentence was just.

B. Different witnesses consistently reported the ceremonies

The judges of Trent questioned various witnesses about the details of the celebration of the Seder, the correspondent readings of the Haggadah, as well as the order of the prayers and their content, the roles of the participants and the phases of the celebration. Based on individual and separate depositions of the witnesses, Toaff reconstitutes those ceremonies showing that they actually existed and were not invented, which prove the objectivity of the Catholic judges. The following reports describe the ritual Seder meals on the two evenings before Passover.

Samuel of Nuremberg, the head of the Hebrew community of Trent, described the principal parts of the Seder to the judges: He provided the unleavened bread baked in his own oven, especially the shimmurim, the solemn and symbolic breads, carefully prepared by himself and his wife before being put in the oven. (p. 138)

Tobias of Magdeburg, a Jewish physician specialized in optometry, specified that those breads had to be put in the oven immediately after preparation in order not to allow fermentation, which would make them unacceptable for eating according to the rite.

After those breads were duly prepared, Samuel spoke the ritual phrase: “These breads have been prepared according to the rules.” (p. 139)

All the witnesses reported the same details of the Seder meal, which used the blood of a Catholic boy

|

Samuel also recounted that at this point, he, as the chief of the family, sat at the head of the table and poured the wine into the beakers while reciting the words of the blessing for the feast (kiddush). Then, the other guests poured themselves wine into their cups. The tray with three shimmurim was placed in the center of the table, awaiting the collective recitation of the Haggadah. Tobias went into greater detail, explaining how the family mixed the wine in the cup and how a tray with the shimmurim, the egg, meats and other foods were placed on the central part of the table to be eaten during the supper. (ibid.)

Mohar (or Meir), the son of Moses of Wurzburg, recalled in his deposition that at this point all the participants raised together the tray with the shimmurin and other foods and recited the introductory formula of the Haggadah in Aramaic, which opened with the words Ha lachmà aniya, “This is the bread of the affliction that our fathers ate in the land of Egypt.” (pp. 139-140)

This was followed by the recitation of the 10 plagues of Egypt, which the Ashkenazy Jews called the 10 curses. Because of the heavy German pronunciation of the Hebrew by the witnesses their words were not clear. Toaff shows how those words actually correspond to the traditional Jewish liturgy. In italics are the transliterations of the plagues in Hebrew; between parenthesis is how they were pronounced by Samuel of Nuremberg and the other witnesses and registered in the acts of the process: Dam (dam) the blood; zefardea (izzardea), the frogs; kinim (chynim), the lice; arov (heroff), the wild beasts; dever (dever), the pestilence of the animals; shechim (ssyn), the ulcers; barad (porech or bored), the hail; arbeh (harbe), the locusts; choshekh (hossen), the darkness. The last one was makkat bechorot (maschus pochoros), the death of the firstborns. (p. 140)

While reciting each plague, the head of family would dip the index finger of his right hand into the cup of wine and would sprinkle it on the table.

Anna of Montagnana, daughter-in-law of Samuel, also recalled this ritual of sprinkling wine on the table while reciting the curses, although she did not remember the precise order. Tobias also confirmed this ritual and was able to repeat precisely the exact order of the ceremony and the 10 plagues, but did not know the exact translation of each Hebrew word. (ibid.)

Moses of Wurzburg remembered the same ceremony he used to perform when he was a head of family in Speyer and Mainz (Germany). While sprinkling the wine on the table, he informed the inquisitors of Trent that, according to the Ashkenazy tradition, “the head of the family added these words: ‘Thus we ask God to make these curses fall on the Gentiles, enemies of the faith of the Jews,’ a clear reference to Christians.” (p. 142)

According to Israel Wolgang, another accomplice in the murder of St. Simon of Trent, the influential Venetian banker Salomon of Piove di Sacco, as well as the banker Abraham of Feltre and the physician Rizzardo of Regensburg at Brescia, all participated in similar ritual ceremonies.

Moses of Bamberg, a guest in the house of Angelo of Verona, also testified to seeing the same ceremony at the house of Leo of Mohar in Tortona. He had precise memories of the rituals since his house was located in the district of the Jews of Nuremberg. (ibid.)

A text from a 14th century Sarajevo Haggadah

|

Tobias of Magdeburg, as the head of the family, had directed the Seder, and he reported the same sequence repeated every year without variation. But he told the judges of Trent that after the reading of the Haggadah recalling the 10 plagues, he had added this phrase: “Thus we implore God to similarly send these 10 curses against the Gentiles, who are opposed to the religion of the Hebrews,’ intending to refer particularly to the Christians.” (ibid.)

In his turn, Samuel of Nuremberg said that while sprinkling the wine on the table, he took advantage of the tragedy of the Pharaoh to unambiguously curse the faithful of Christ: “We invoke God to let all these anathemas fall against the enemies of Israel.” (ibid.)

Toaff concludes showing how this practice had continued for a long time: “The Seder thus became an evident display of anti-Christian sentiment, exalted by symbolic and significant acts and ardent imprecations, which now used the great events of the Exodus [of the Jews from Egypt] simply as pretext. In Jewish Venice of the 1600s, the characteristic rituals related to the reading of this part of the Haggadah were still alive and present, as shown by the testimony of Giulio Morosini, which is to be considered as entirely reliable:

“When the head of the family refers to those 10 chastisements, a bowl or basin is brought to him, and as he names each one he dips his finger inside his glass of wine and drips the wine inside the bowl, gradually emptying the contents of the glass as a sign of the curses against the Christians.” (ibid.)

After analyzing other examples, Toaff reaches these conclusions:

-

“In substance, the so-called ‘confessions’ of the defendants during the Trent trials relating to the rituals of the Passover Seder and Haggadah reveal themselves to be precise and trustworthy.” (p. 144)

- The Jews of Trent describing the Seder in which they had participated, were not lying; nor were they under the influence of the judges, who were presumably ignorant of a large part of the ritual being reported to them. If the accused dwelt at length upon the virulent anti-Christian meaning which the ritual had assumed in the tradition of that Franco-German Judaism to which they belonged, they were not going to in unverifiable exaggeration. In their collective mentality, the Passover Seder had been transformed for a long time into a celebration in which the wish for the forthcoming redemption of the people of Israel became an aspiration of revenge and outrage against their Christian persecutors, the current heirs to the wicked Pharaoh of Egypt.” (pp 144-145)

- “It seems obvious that only someone with a very good knowledge of the Seder ritual from within could describe the [precise] order of the gestures and actions as well as the Hebrew formulae used during the different phases of the celebration, and would be capable of supplying such detailed and precise descriptions and explanations. … To imagine that the judges, using torture, dictated those descriptions of the Seder ritual, with the related liturgical formulae in Hebrew, seems hardly credible.” (p. 150)

These consequences are inevitable:

-

The credibility of the tribunal of Trent that examined the death of St. Simon is confirmed against centuries of calumnies by the Jews;

-

The ritual ceremony at which St. Simon was tortured and crucified actually took place.

3. Detailed description of the ritual homicide of St. Simon

These same trustworthy witnesses also gave testimony regarding the death they inflicted on St. Simon. Ariel Toaff reconstitutes the scene based on their words:

“The depositions of the accused in the Trent trial were all in agreement that the infanticide of Simon would have taken place on Friday inside the synagogue, located at the dwelling of Samuel of Nuremberg, and more precisely in the antechamber of the hall where the men normally gathered in prayer. This place, which was separated from the synagogue properly speaking by a door, was intended for the women’s prayers. …

Simon laid out on the almenor with the instruments of torture and bloodletting

|

"The crucifixion of Simon would have been committed on a bench located in the so-called ‘women’s synagogue.’ The boy’s body, already without life, would have been transferred to the central hall of the synagogue and placed on the almemor. The same Tobias confirmed that during the Sabbath liturgy he ‘had seen the boy’s body stretched out on the almemor, which is a table in the center of the synagogue, on which they place books.’

“Angelo of Verona stated that ‘the almemor is a Hebrew word equivalent to the Latin cathedra, seat of prayer; in fact, almemor is the table upon which the five books of Moses are placed and is located in the center of the scola [teaching area]. The boy’s body was laying supine on the almemor (during the Sabbath service).’ The body was wrapped in a mappah (wimple) made of a multicolored and damask silk, a cloth the size of a hand towel used to cover the rolls of the Law after the reading.” (p. 164)

Toaff continues: “The depositions of the accused actually provide clear indications of their obvious intent to transform the child’s crucifixion into a symbolic commemoration of the Passion of Christ, referred to contemptuously as ‘the suspended one, Jesus the heretic.’ (p. 165)

“In effect, the so-called Hebrew formulae, which were said to have been pronounced on that occasion, cannot be dismissed as the expression of a mysterious, imaginary language, intended to confer Satanic connotations on the report of the cruel ritual murder to satisfy the wishes of the inquisitors. With some effort, due to the loose transliteration by the Italian notaries of long, complicated phrases spoken in Ashkenazy Hebrew with a thick German accent, the formulae can be reconstructed quite satisfactorily, revealing their marked and verifiable anti-Christian tenor.” (pp. 165-166)

Toaff substantiates this affirmation with the testimony of Moses of Wurzburg, who repeated to the judges the Hebrew formula spoken over the boy, which translates: “You will be martyred as Jesus, the suspended God of the Christians, was martyred, and thus may it happen to all our enemies.” (p.166)

A similar statement was made by Samuel of Nuremberg, who translated the Hebrew with these words: “In contempt and shame of the suspended Jesus, and thus may it happen to all our enemies.” (ibid.)

Toaff goes on to analyze the Hebrew formulae as pronounced by those Jews and registered by the notaries of the Trent trial who did not know the language. He concludes: “Taking into account that the Hebrew was spoken with the Ashkenazy pronunciation, the invective should be reconstructed as follows, leaving little margin for doubt: “You are crucified and pierced like the suspended Jesus, in ignominy and shame, as he was.” (ibid.)

He then comments: “For the participants in the ritual, the Christian child had lost his own identity (if he ever had had any in their eyes) and had actually been transformed into the ‘crucified and suspended Jesus.” (ibid.)

For any Catholic reading this description, no doubt remains that the ritual homicide of St. Simon of Trent took place and was inflicted by those Jews, as traditionally reported until Paul VI, who denied to St. Simon of Trent the title of Saint and removed him from the Roman Martyrology.

4. Ritual properties attributed to the blood of boys

Toaff also studies the consumption of blood, both animal and human, by the Ashkenazy Jews, who had moved from Germany to northern Italy.

A. Blood of Jewish boys

On the use of the blood of Jewish boys, A.T. affirms:

“It seems that there cannot be any doubt to the fact that, through an old tradition, never interrupted, empirical healers, cabalists and herbal alchemists prescribed powdered blood as a coagulant healer of proven efficacy during circumcision or hemorrhage. …

“The ritual responses of the gheonim - the heads of the rabbinical academies of Babylon active between the 7th and 11th centuries - refer to the local custom of boiling perfumes and spices in water to make it fragrant and aromatic, and of circumcising the boys by making their blood gush into that liquid until its color would change.’

"‘It was at this point,’ the rabbinical response continues, ‘that all the young males wash themselves in that water in memory of the blood of the pact, which has united God to our patriarch Abraham.’ In this rite, of a propitiatory nature, the blood from the circumcision united with the perfumed liquid would have the capacity to transform itself into a powerful aphrodisiac, a fortifying remedy useful to invigorate the loving desires and procreative capacities of the initiated males.

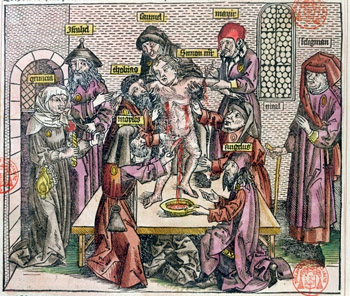

Above,a rabbi sucks the penis of a boy after the circumcision to "benefit" from his blood; below, women waiting to snatch the foreskin at a ritual circumcision

|

“One form of magical cannibalism, related to the circumcision, is founded on a custom widespread among both the Ashkenazy Jewish communities and those of the Mediterranean area. The women present at the circumcision ceremony who had not yet been blessed with a male offspring anxiously awaited the cutting of the foreskin of the child. Then, without any inhibition, as if at pre-established signal, they would hurl themselves to catch that piece of bloody flesh. The most fortunate would snatch it and swallow it immediately, before she could be surpassed by the competing women, who were no less motivated or aggressive.” (pp. 85, 86)

After enumerating more uses of human blood, Toaff notes: “In conclusion, the customs of the Hebrews from the German lands, constant throughout their history, of consuming potions and medicines made of animal blood, without regard to the ritual prohibition of the Torah, is incontrovertibly confirmed by authoritative and significant Hebrew texts.

"As we have seen, the compendiums of segullot (2) in many cases broadened the permission for using human blood, to be ministered dried and dissolved in another liquid, which was recommended not only for therapeutic purposes, but also for spells and exorcisms of various types.” (p. 92)

For anyone with a Catholic Western sensibility these ritual acts linked to circumcisions cannot be more repulsive and disgusting.

B. The blood of Christian boys

As reported in the book Bloody Passovers, except for the two mentioned usages of liquid blood from the circumcision of Jewish boys, most of the blood used by Jews for ritual or medicinal purposes was dried over fire and reduced to grains or power. In this state, the blood was sold by itinerant salesmen who, to guarantee their clientele that the product they offered was authentic, had a certificate signed by the rabbi in whose synagogue the blood had been taken from a Christian boy, like St. Simon in Trent. It is to this macabre commerce that the next excerpts refer.

The text below is self-explanatory and requires no commentary:

The martyrdom of Simon of Trent with the main personages involved identified

|

“The records of the Trent trial reveal not only the generalized use of blood by the German Jews for curative and magic purposes, but also the need that they felt, according to the inquisitors, to supply themselves with Christian blood (and in particular that of a baptized boy) above all for the celebration of the Pesach, the Jewish Passover.

"In this case it was not enough to turn to specialized, acknowledged retailers of blood or itinerant herb alchemists to obtain the required goods. It was necessary to ascertain that, despite the facility for falsification and adulteration, the object of purchase was surely that precious and much sought-after commodity, the blood of a Christian boy.” (pp. 92-93)

Toaff then cites witnesses who provide verifiable names and places for the commerce of the ritual blood:

“Old Moses of Würzburg assured the judges [of the Trent Tribunal] that, in his long career, he had always acquired the blood of Christian boys from trustworthy persons or retailers bearing the required written rabbinical guarantees, which he called ‘testimonial letters.’

“To not be too vague on this topic, Isaac of Gridel, cook in the house of Angelo of Verona, recalled how the wealthier Jews of Cleberg, a city under the lordship of Filippo of Rossa, acquired the blood of Christian boys from a rabbi named Simon, who lived in Frankfurt, then a free city. This Simon of Frankfurt can certainly be identified with Shimon Katz, rabbi of the community of Frankfurt over Main from 1462 to 1478, the year of his death. Shimon was also the head of the local rabbinical tribunal.

“Rabbi Shimon maintained close contact with the spiritual leaders of the Ashkenazy communities of Northern Italy, and a close friendship with Yoseph Colon, the almost undisputed religious head of the Italian Jews of German origin. To consider him as a common trafficker in Christian blood, as Isaac the cook pretended, seems to me very disproportionate and hardly credible, in the absence of other information to support such a singular thesis.

“Undoubtedly more serious and worthy of consideration, even if extorted by the cruel means of coercion, was the related testimony of Samuel of Nuremberg, undisputed head of the Jews of Trent. Samuel confessed to his inquisitors that the itinerant peddler Orso (Dov) of Saxony, from whom he had obtained blood, presumably that of a Christian boy, had credential letters signed by ‘Moises de Hol of Saxony, Iudeorum principalis magister.’

Above, each head of family must prepare the breads for the ritual meals and mix dry blood in its dough; below, a rabbi provides the unleavened bread to be eaten

|

“There appears to be no doubt that this Moses is identical with rabbi Moses of Halle, head of the yeshivah [rabbinic academy], who together with his family, enjoyed privileges granted by the Archbishop of Magdeburg in 1442 and later by the Emperor Frederick III in 1446. These privileges included the use of the title of Jodenmeister, or principalis magister Iudeorum [principal master of the Jews], as Moses is described in the deposition of Samuel of Nuremberg.” (pp. 93-94, see also pp. 151-152)

As Toaff progresses, he shakes off some of his initial insecurities and admits without too many problems that those ritual infanticides took place and that the blood was used in the Jewish Passover ceremonies.

For example, he begins his chapter 12 with these words:

“The use of blood of a Christian boy in the celebration of the Jewish Passover was apparently the object of precise regulation, at least according to the depositions of all the defendants in the Trent trials. These depositions describe exactly what was prohibited, what was permitted and what was tolerated in meticulous detail. Every eventuality was foreseen and dealt with, and the use of the blood was governed by a broad and exhaustive casuistic.

“The blood, powdered or dried, was mixed into the dough of the unleavened or ‘solemn’ bread, the shimmurim – not ordinary bread. Indeed, the shimmurim, three loaves for each one of the two evenings during which the ritual Seder dinner was served, were considered one of the principal symbolic foods of the feast, and their accurate preparation and baking occurred during the days preceding the advent of the Passover.” (p. 146)

He continues, “During the Seder, the blood had to be dissolved into the wine immediately before the recitation of the 10 curses of Egypt. The wine poured into the basin or pot was later thrown away. The performance of the ritual required only a minimal quantity of blood in powdered form, equal to the size of a lentil.

“The obligation to procure blood and use it in the Passover ritual was the exclusive responsibility of the head of the family, that is, the one who had under his authority a wife and children. … In view of the difficulty of procuring such a rare and expensive ingredient, it was regulated that the wealthier Jews should provide it for the poorer ones, an eccentric form of beneficence to assist heads of family not favored by fortune.” (ibid.)

The father should also mix blood in the wine to be served at the Passover meal

|

Among the testimonies Toaff presents that of Samuel of Nuremberg, who reported: “The evening before the Passover, when they stir the dough with which the unleavened bread (the shimmurim) is later prepared, the head of the family takes the blood of a Christian boy and mixes it into the dough, while it is being kneaded, using it in proportion to the quantity he has, keeping in mind that the measure of a lentil is sufficient. The head of the family sometimes performs this operation in the presence of those kneading the unleavened bread, and sometimes without their knowledge, based on whether or not they can be trusted.” (ibid.)

The details of mixing the blood of a Christian boy into the wine were confirmed, among others, by Samuel of Nuremberg, Angelo of Verona, Tobias of Magdeburg, Moses of Würzburg, as well as by the convert Giovanni da Feltre, who had seen his father perform the ritual while still living at Landshut in Bavaria. (pp. 148-149)

Given the numerous testimonies cited by Toaff, it is almost impossible not to accept that, at least among the Ashkenazy Jews of that time, the anti-natural and cruel practice of killing Christian boys existed.

5. Ceremonies and texts against Our Lord Jesus Christ

In numbers 3 and 4B, we saw some examples of how the Jewish Passover ceremonies included express manifestations of hatred against Our Lord Jesus Christ. Here we will transcribe more texts confirming the presence of such offenses in the Passover ritual, as well as in the feast of Purim and in classical texts of Judaism

A. More data on the ceremonies of Passover

Besides the mention of offenses against Our Lord made during Passover, the following statements of witnesses presented by Toaff are worthy of attention:

-

Angelo of Verona explained to the judges that the ritual preparation of the unleavened breads was carried out, above all, “as a sign of outrage against Jesus Christ whom the Christians claim is their God.” (p. 147)

- The same defendant continued: “Consuming the unleavened bread made with Christian blood means that, just as the body and the power of Jesus Christ, the God of the Christians, went down to perdition with his death, thus the Christian blood in the unleavened bread shall be ingested and completely consumed.” (p. 148)

-

Moses of Würzburg stressed the significance of the blood rites: “The law of Moses commands the Hebrews that, in the days of Passover, every head of family must take the blood of a spotless male lamb and place it (as a sign) under the thresholds of the doors of his house. However, since this custom of taking blood of the perfect male lamb has been lost, in its place (the Jews) now use the blood of a Christian boy … and they do this and consider it necessary as a negative memorial (of the passion) of Jesus, God of the Christians, who was a male and not female, and was suspended and died on the cross in torment, in a shameful and vile way.” (p. 153)

-

Vital of Weissenburg declared to the judges: “We use the blood as a sad memorial of Jesus … in outrage and contempt of Jesus, God of the Christians, and every year we make the memorial of that passion …; in fact, the Jews perform the memorial of the passion of Jesus every year, by mixing the blood of a Christian boy into their unleavened breads.” (p. 153)

The prescriptions against Our Lord for the Jewish Passover were established in the Talmud of Babylon, in the 5th century

|

- Samuel of Nuremberg “vaguely attributed these traditions to the rabbis of the Talmud (of Babylon), who were said to have introduced it in a very remote epoch, ‘before Christianity reached its present day power.’ Those scholars, gathering together at a conference, would have reached the conclusion that the blood of a Christian boy would be very beneficial to the salvation of their souls, insofar as the blood was extracted during the memorial ritual of the passion of Jesus, as a sign of contempt and scorn for the Christian religion. In this counter-ritual, the innocent boy, who had to be less than seven years and be of the male sex like Jesus, was crucified among torments and expressions of execration, as had happened to Christ.” (p. 154)

- Moses of Würzburg revealed that the blood ritual was not recorded in any written scripts of Judaism, but was transmitted orally and in secret by the rabbis and scholars in Jewish law. (p. 154) (3)

A.T. gives us his opinion on the ensemble of the Passover ceremonies:

“The rite of the wine, or blood, and of the curses had a double significance. On the one hand, it was intended to remember the miraculous salvation of Israel … in Egypt. On the other hand, it was intended to bring closer final redemption, prepared for through God’s vengeance on the Gentiles who had failed to recognize him and had persecuted the chosen people. The memorial of the passion of Christ, re-enacted and celebrated in the form of an anti-ritual, remarkably exemplified the fate destined for Israel’s enemies. The blood of a Christian boy, a new agnus Dei, and the consumption of his blood, were premonitory signs of the proximate ruin of Israel’s indomitable and implacable persecutors, the followers of a false and mendacious faith.” (p. 153)

B. The Purim feast

In the Jewish calendar, the Passover comes one month after the feast of Purim, which commemorates the salvation of the Jewish people in Persia during the reign of King Ahasuerus I from the threat of extermination, caused by the plotting of the King’s minister Haman. The book of Esther, which recalls those events and the roles of that heroine and her uncle, Mordechai, ends with the hanging of Haman and his 10 sons, as well as the beneficial massacre of the enemies of Israel. In his Rituals, Leon of Modena encouraged carnival celebrations and opulent banquets to be carried out at thePurim feast, where restraint and inhibition were set aside.

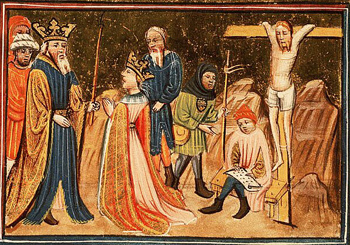

The feast of Purim celebrates the hanging of Haman, above, unduly linked with the crucifixion of Our Lord Jesus Christ; below, "orthodox" Jews at Purim

|

Toaff continues: “For a number of reasons, one being its frequent proximity to Holy Week, Purim acquired openly anti-Christian connotations. Its celebrations became suggestive in this sense, both in form and substance, sometimes boldly and overtly. Haman, equated with that other biblical archenemy of the Jews, Amalek (Deut 25:17-19) … was transformed over time into Jesus, the false Messiah, whose impious followers were once threatening the extermination of the chosen people.

“Further, Haman was killed, suspended liked Jesus, and there was no lack of convincing commentators reinforcing this paragon. Haman’s gallows was interpreted as a cross … and the execution of King Ahasuereus’ belligerent minister was presented as a true and proper crucifixion. The equation relating Amalek, Haman and Christ was obvious. Haman, who in the Biblical text is called talui, ‘the suspended one’, was confused with the one who in all the anti-Christian Hebrew texts was called the Talui by antonomasia, that is, the crucified Christ.” (pp. 112)

Toaff points out the many testimonies describing the rituals during the carnival of Purim that vilify and outrage the image of Haman, reconstituted in the semblance of Christ suspended from the cross.

He continues: “Turning back centuries, however, ... we must note that the ritual of Purim did not always conclude with the bloodless crucifixion of an effigy of Haman. Sometimes a flesh and blood Christian was taken and truly crucified during the wild revelry of the Jewish carnival.” (p. 114)

Some of the cases of crucifixions of Christians at the feast of Purim that Toaff reports include:

-

One in the 5th century, quoted from a Catholic chronicle: The Jews in Inmestar, a city close to Antioch, “took to deriding the Christians and Christ himself in their boastings. They ridiculed the cross and anyone who believed in the crucifix, putting the following into play. They took a Christian boy, tied him to a cross and suspended him there. First, they made him the object of mockery and jokes; then, after some time, they lost control of themselves and mistreated him so much that they killed him.” (pp. 114-115)

- One in the 12th century in Brie-Comte-Robert, France, regarding a servant of the Duchess of Champagne, quoted from a Jewish chronicle: “A perfidious Christian had killed a Jew in the city of Brie … Then the other Jews, his relatives, went to the lady of those lands (the Duchess of Champagne) and begged her to hand over the murderer, who was a servant of the King of France. They bribed her with their money so that they could crucify the assassin. And they crucified him on the eve of Purim.” (p. 115)

A list of other offenses made against Christ and Christians at the Purim feast and condemned by Catholic authorities can be found on p. 116.

C. The books of Toledot Yeshu & the Talmud

To complete the picture of the offenses the Jews made against Our Lord Jesus Christ, Toaff gives a historical summary of the book Toledot Yeshu, literally The History of Jesus. He writes:

Above, the Toledot Yeshu is a book highly offensive to Our Lord & Our Lady; below, Peter Schafer analyzes injuries in the Talmud against Jesus Christ

|

“At this point it is opportune to refer to the most significant text of the Jewish anti-Christian polemic, the Toledot Yeshu, or the “Jewish counter-gospel.” It is a virulently offensive biography of Jesus, dated between the 4th and 8th centuries, disseminated first in Aramaic and later in Hebrew in more or less different versions.

"The text had the clear intention of distorting the Christian religious identity by demolishing and ridiculing its memory. Systematic contempt for the figures of Jesus and the Virgin Mary, presented as a woman of bad life, formed the basis of a satirical and mocking tale to be sung, presented as the antithesis of the Gospels themselves.

“It is not surprising that this classic of anti-Christian polemic found eager and receptive readers among Jews all over the world, from Islamic countries to Spain and Italy. It is still less surprising that the Jews of Germany adopted this text enthusiastically and devoutly, as attested by the facts that almost all the hand-written copies of Toledot Yeshu appear to be written by the Ashkenazy copyists and all the translations of this text into the Jewish-Hebrew dialect are in Yiddish.” (p. 158)

Further on Toaff comments that a century after the Trent trials, the despicable words spoken over the corpse of the martyr Simon – taken from the Toledot Yeshu – “were still alive and well among the Ashkenazy in the valleys of the Loire and the Rhone, the Rhine and the Danube, the Elba and the Vistula, and the communities that migrated beyond the Alps to the plains of the Po and the gulf of Venice.” (p. 171)

It is not just the Toledot Yeshu that makes vile offenses against Our Lord, but also the Talmud, Judaism’s principal book. Toaff describes similar offenses found in it:

“Another outrageous assertion about the Christian religion very widespread among Jews of German origin was based on the Talmudic dictum that Jesus was to suffer punishment in the next world, condemned to immersion in “boiling excrement.” (Babylonian Talmud, Ghittin, c. 57a).

“The Jewish bankers of the Dukedom of Milan accused of contempt for the Christian faith in 1488 were asked whether their texts claimed that Jesus was condemned to the pains of hell and placed in a pot filled with excrement. Salomon Galli di Brescello, Jew from Vigevano, had no difficulty in admitting that he had indeed read that malodorous prophecy in a booklet that passed through his hands in Rome during the pontificate of Sixtus IV. Salomon of Como and Isaac of Parma, a resident of Castelnuovo Scrivia, confirmed that they, too, knew the Jewish texts asserting that Jesus was destined in the future world to be immersed in a bath of steaming feces.” (p. 171)

The ensemble of offenses reported in this review is so vile that I do not have words to describe it. It was as an act of reparation to the purity of the Queen of Heaven and to the glory of her Divine Son that I made this meticulous study of this book to expose its main content to the public.

6. Conclusion

In my opinion, Bloody Passovers is an important document to show the blasphemous and anti-Catholic religious customs of the Ashkenazy Jews at least until the 15th century with extensions to the 17th century (see p. 142). Reading it left me with some final questions to which I did not find objective answers:

1. Ariel Toaff says that the macabre rituals he describes were not practiced by all Jews. In several parts of his book, he proudly exempts the Italian Jews from all the charges he reports in his book . However, he also states that the Ashkenazy Jews consider themselves to be the most authentic expression of Judaism and that the current to which he belongs today is considered liberal and lax.

Vicki Polin reveals her Jewish family continues today the ritual sacrifices of children - watch the video here

|

Since, to my knowledge, this division between “orthodox and liberals” still continues, the question that remains is: To what degree are these same ceremonies still practiced inside the Ashkenazy observance until today? Given that many of these Ashkenazy customs appear to be based on the Talmud, to what degree are they accepted or, at least, viewed with complacence by all of Judaism even if some currents do not practice them?

2. Ariel Toaff demonstrated with solid arguments that the judges of Trent could not have invented what was registered in the depositions of the defendants accused of killing St. Simon of Trent: The judges could not have known the complex ritual of the Jewish ceremonies and the contorted Hebrew religious language pronounced with a strong German accent, along with other regional linguistic corruptions. Further, all the depositions of the defendants are in perfect accordance with the Ashkenazy rituals, which the judges also did not know.

These arguments put to rest the contentions of Jewish apologists that the Jews at the Trent trials were innocent and consequently that the Inquisition was unjust. The demonstrated honesty of the Trent Tribunal leads us to believe that other Catholic tribunals that issued similar sentences against the Jews for similar crimes were also honest. But how can this be proved since most of the documents have disappeared? And how can their disappearance be explained?

In various parts of his book, Toaff reports cases of wealthy Jews using their money to bribe Catholic authorities in order to achieve their aims. If the use of this method is an accepted fact, how can we exclude that the missing documents of other Catholic tribunals were destroyed by means of the same system of subornment?

3. Although it is known that Judaism has numerous factions - I would say as many as Protestantism – in the face of the Catholic Church they always unite and Judaism appears as a monolithic block. We have seen Jews from the most opposed tendencies join together and assist one another when one or another of their currents are attacked by Catholics for some reason.

It seems to me that this book by Ariel Toaff breaks this monolithic “equilibrium.” Here a current inside Judaism appears and says: “The Catholics acted justly at Trent because you – the Ashkenazi Jews – did actually kill Simon; here are the proofs. Further, you habitually killed Catholic boys to carry out your fanatical rites.”

What is happening inside Judaism for one of its important representatives to strike this mortal blow against a whole current, the Ashkenazy observance? What is the cause of this unheard-of rupture?

These are questions that I invite my reader to keep in mind to see if an answer will appear in the days to come.

1. On Holy Thursday of the year 1475, the child Simon, son of a gardener, was missed by his parents. On the evening of Easter Sunday his mutilated body was found in a ditch. Several Jews were accused of ritual murder. The case was prosecuted by the Tribunal of Inquisition and the Jews were sentenced to death. It was retried twice, the last time before the court of Pope Sixtus IV, and both times the sentence was confirmed.

2. Literally, segullah or its plural segullot, means secret, secrets. It refers to the secret usage of many remedies composed of human blood that are transmitted orally among the cabalist Ashkenazy Jews. One of them referred to in the text is the practice of swallowing the foreskin of the sexual organ of a circumcised boy. Later, this secret became known and many written texts testify to its usage, like the ones quoted in Toaff’s book on page 86.

3. Ariel Toaff does not consider these last two statements as trustworthy. I believe he had to take this position for prudential reasons; otherwise his accusation against the Ashkenazy Jews could be extended to include all of Judaism. Although on page 154 Toaff expresses his doubts about these statements, on pages 158-159 he quotes a text that confirms what these two witnesses affirmed. It is a curious example of the dialectical method employed by the author.

Posted February 13, 2012

Related Topics of Interest

Bloody Passovers Reported by a Jewish Scholar Bloody Passovers Reported by a Jewish Scholar

Is the Catholic Church Becoming a Branch of the Synagogue? Is the Catholic Church Becoming a Branch of the Synagogue?

John Paul II Blessed by the Rabbis John Paul II Blessed by the Rabbis

Benedict XVI inside the Synagogue of Cologne Benedict XVI inside the Synagogue of Cologne

The Rational of Judgment The Rational of Judgment

The Deicide and the Council The Deicide and the Council

Related Works of Interest

|

|

Book Reviews | Home | Books | CDs | Search | Contact Us | Donate

© 2002-

Tradition in Action, Inc. All Rights Reserved

|

|

|