Catholic Customs

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Grand Medieval Christmas Feast

After the profound mysteries of Midnight Mass, people returned to their homes to enjoy hearty meals with no semblance of fasting. In regions where the main meal was eaten before Mass, the pastries and sweets were often reserved for afterwards. To honor Our Lord and the Twelve Apostles, thirteen desserts sat on the post-Midnight Mass Christmas table in Provence, France. (1)

The large Christmas meal, served either during the hours following Midnight Mass or in the afternoon on Christmas Day would consist of multiple courses, featuring the choicest staples of the harvest, meats, breads and cakes adorned with symbols of Christmas.

Toasting the Christmas feast

To begin so joyous a feast, toasts with spiced ale or wine were made asking for the blessings of Christ upon all and giving a salute to Christmas.

In England Christmas was toasted with “Wassail.” Wassheil is derived from the Old English word waes haell meaning “be healthy” or “good health.” (2) The mulled ale or wine that was used in the toast also became known as Wassail.

In England Christmas was toasted with “Wassail.” Wassheil is derived from the Old English word waes haell meaning “be healthy” or “good health.” (2) The mulled ale or wine that was used in the toast also became known as Wassail.

The English referred to the white roasted apple flesh that floated in the ale as "lamb’s wool" and in some areas, such as Ireland where milk was added to the drink, the drink itself was called “lamb’s wool.” The French, Germans and Scandinavians too had their own versions of spiced mulled wine into which various dried fruit and nuts were added.

An ancient ritual called “doppa I grytan” (“dipping in the kettle”) began the meal in Sweden and Norway. Each family member took a piece of vörtbröd (brown bread) and dipped it in the kettle of broth in which the Christmas meat had been cooked to honor their ancestors who enjoyed this dish as their Christmas feast hundreds of year ago. After the last person dipped his bread, the father began the feast by giving a toast in honor of Christmas. (3)

The festive Christmas meat: The boar, pig or goose

Thus, Christmas being duly saluted, the fasting people looked expectedly for the meat from which they had abstained for several weeks. Regardless of which prize meat was enjoyed, it was not feasted on until after Midnight Mass. An old Norwegian custom dictates that the first bite of the Christmas pig must be taken between midnight and daybreak. (4)

Throughout Christendom from the Northern villages of Scandinavia to the Mediterranean towns of Greece, the pig or boar was an important part of the Christmas meal. The peasants often butchered their fattest pig a few days before Christmas so as to present the freshest meat on the Christmas table and to have an abundance that would last all Twelve Days.

Throughout Christendom from the Northern villages of Scandinavia to the Mediterranean towns of Greece, the pig or boar was an important part of the Christmas meal. The peasants often butchered their fattest pig a few days before Christmas so as to present the freshest meat on the Christmas table and to have an abundance that would last all Twelve Days.

Nobles and Monarchs procured their meat through daring feats that suited the ideals of their class. During September and October in Northern lands, hunters and their boar hounds journeyed to the forest to search for the boars and bring down the largest animal they could find. The prized head was specially prepared, and when it was carried into the hall, the valor of the hunters was admired by all, for boar hunting was a dangerous sport that could end in the death of a valiant hunter.

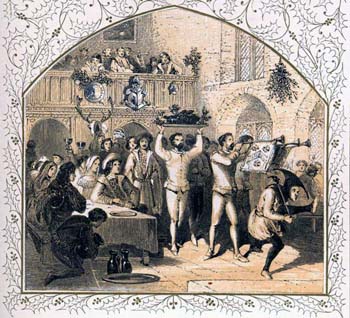

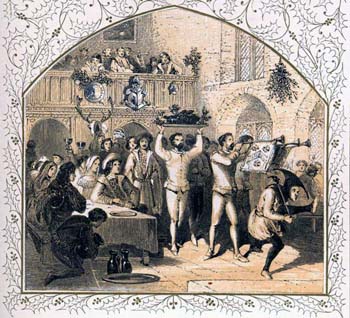

In the ceremonial bringing in of the boar’s head of Medieval England, the boar’s head was carried into the hall on a large platter surrounded by rosemary and bay, preceded by trumpeters and followed by mummers. The bearer of the head sang:

Caput apri defero,

Reddens Laudes Domino.

Quid estis in convivio. (5)

The boar’s head in hand bring I,

With garlands gay and rosemary;

I pray you all sing merrily.

Before the head was carved, the chief of the household laid his hand on the dish and swore to be a man of honor faithful to his family and to the obligations arising from his position. Every man at the hall followed the lord in taking their oaths.

The symbolism of the boar was important in Norse mythology in which the god Frey is given a boar. This golden-bristled boar, which darkness could never overtake, represented the sun for its bristles shone like the sun’s rays. In Norse folklore, the boar was also said to have first taught man the art of plowing and thus also became symbolic of the golden grain. (6)

Having shed its pagan past, the boar still makes a fitting symbol for Christmas since it represents light and wheat, which are fulfilled in the Babe of Bethlehem Who is the Sun of Justice and the Bread of Life.

Christmas fowl

Fowl was also traditionally served in many places, because in the Middle Ages Christmas gifts and payments were made in the form of live fowl that would be fattened on raisins and milk. (7)

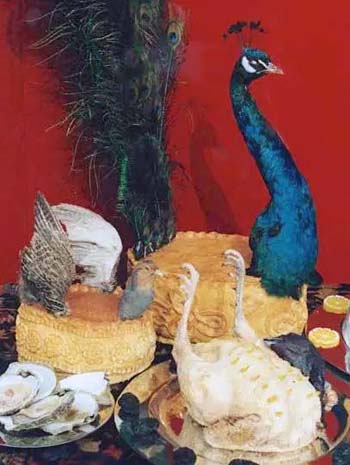

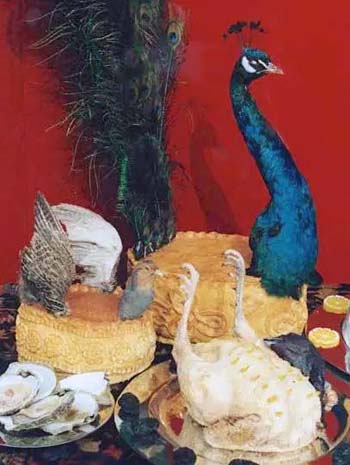

In Medieval English halls, peacock was the second dish of honor and it was the only dish given the privilege of being carried into the hall by a noble lady distinguished by birth or beauty. A group of other reputable ladies followed her as she processed to the seat of the master of the house to lay the bird before him.

In Medieval English halls, peacock was the second dish of honor and it was the only dish given the privilege of being carried into the hall by a noble lady distinguished by birth or beauty. A group of other reputable ladies followed her as she processed to the seat of the master of the house to lay the bird before him.

The beautifully arranged peacock was first skinned, stuffed with sweet spices and roasted, and then duly decorated so that the marvelous green, blue and purple feathers splayed out in colorful fanfare. (8)

So cherished were peacock feathers that they were even used to adorn churches in Christmas. Thus this glorious bird that symbolized the Resurrection and immortality was made to pay homage to the Infant King whose birth brought hope for eternal life.

In Sweden and Denmark, a fat goose was served in every home from the King’s palace to the peasant’s cottage. Many Austrians and Germans also served goose, and Provençal families ate goose in honor of the goose that was said to have greeted the Three Wise Men with his quacking when they approached the Christ Child. (9)

Ever since the discovery of America in the 16th century and the introduction of the turkey to the Old World, turkey has become a popular feature of the Christmas meal in many areas of Europe, including Spain and France.

So prized was this fowl from the New World that it was called the “monarch of the Christmas table” in the 18thcentury. The Spaniards traditionally stuffed their turkeys with sausage, bacon or ham, olive oil, garlic, onions, mushrooms, chestnuts or pine nuts and dried or fresh fruit, the stuffing varying from region to region. (10)

The Spaniards repaid the New World for this kingly addition to their feast by transmitting to it the grandeur of their Christmas feasts. Mexicans feasted on a richly spiced stuffed roast turkey along with tamales. In South America, Christmas falls at Summer so there the Christmas meals were often eaten outside in gardens filled with beautiful flowers. (11)

The Spaniards repaid the New World for this kingly addition to their feast by transmitting to it the grandeur of their Christmas feasts. Mexicans feasted on a richly spiced stuffed roast turkey along with tamales. In South America, Christmas falls at Summer so there the Christmas meals were often eaten outside in gardens filled with beautiful flowers. (11)

Other special meat dishes graced the table in different lands. In many British homes, roast beef was served instead of goose. In Galicia, Spain, the center of the meal was a suckling pig or a meat pie, while in the rural parts of Aragon a dish of lamb and chicken held the place of honor at the table.

Suckling pig also crowned the feast in Argentina and Serbia. Hare, venison or other game meat was popular amongst the Dutch and Belgians.

In Luxembourg, Austria and other Germanic lands, families feasted on sausages, while the French Canadians enjoyed a richly spiced meat pie called Tourtière.

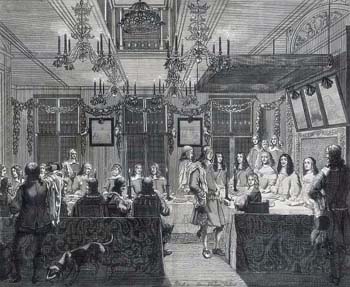

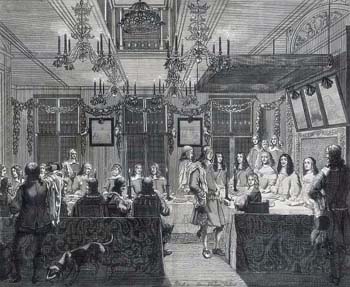

Perhaps nowhere, even to this day, is the Christmas feast more lavish than in France where the meal following the Midnight Mass is called the Réveillon, which can consist of a dozen or more small courses spread throughout three hours or more.

Perhaps nowhere, even to this day, is the Christmas feast more lavish than in France where the meal following the Midnight Mass is called the Réveillon, which can consist of a dozen or more small courses spread throughout three hours or more.

Country homes enjoy more simple repasts, but in the homes of the wealthy and bourgeoise families in cities, there are always multiple courses often including pâté, seafood, truffles and large birds garnished splendidly with symbols of Christmas. (12)

The Christmas meals of the past were very solemn and sacral, even in peasant homes. Our Christmas meals can also be graced with the sacrality of the past if we follow the old ways of ceremony and seriousness, and leave behind the banal and worldly ways of modern Christmas celebrations. Then, our earthly feast will fill our souls with a spiritual joy reminiscent of the joy of the Saints in Heaven.

Continued

Posted December 20, 2024

The large Christmas meal, served either during the hours following Midnight Mass or in the afternoon on Christmas Day would consist of multiple courses, featuring the choicest staples of the harvest, meats, breads and cakes adorned with symbols of Christmas.

Toasting the Christmas feast

To begin so joyous a feast, toasts with spiced ale or wine were made asking for the blessings of Christ upon all and giving a salute to Christmas.

A medieval servant holding the Wassail bowl

The English referred to the white roasted apple flesh that floated in the ale as "lamb’s wool" and in some areas, such as Ireland where milk was added to the drink, the drink itself was called “lamb’s wool.” The French, Germans and Scandinavians too had their own versions of spiced mulled wine into which various dried fruit and nuts were added.

An ancient ritual called “doppa I grytan” (“dipping in the kettle”) began the meal in Sweden and Norway. Each family member took a piece of vörtbröd (brown bread) and dipped it in the kettle of broth in which the Christmas meat had been cooked to honor their ancestors who enjoyed this dish as their Christmas feast hundreds of year ago. After the last person dipped his bread, the father began the feast by giving a toast in honor of Christmas. (3)

The festive Christmas meat: The boar, pig or goose

Thus, Christmas being duly saluted, the fasting people looked expectedly for the meat from which they had abstained for several weeks. Regardless of which prize meat was enjoyed, it was not feasted on until after Midnight Mass. An old Norwegian custom dictates that the first bite of the Christmas pig must be taken between midnight and daybreak. (4)

Peasants butchering the Christmas pig;

below, nobles hunting the wild boar

Nobles and Monarchs procured their meat through daring feats that suited the ideals of their class. During September and October in Northern lands, hunters and their boar hounds journeyed to the forest to search for the boars and bring down the largest animal they could find. The prized head was specially prepared, and when it was carried into the hall, the valor of the hunters was admired by all, for boar hunting was a dangerous sport that could end in the death of a valiant hunter.

In the ceremonial bringing in of the boar’s head of Medieval England, the boar’s head was carried into the hall on a large platter surrounded by rosemary and bay, preceded by trumpeters and followed by mummers. The bearer of the head sang:

Reddens Laudes Domino.

Quid estis in convivio. (5)

The boar’s head in hand bring I,

With garlands gay and rosemary;

I pray you all sing merrily.

Before the head was carved, the chief of the household laid his hand on the dish and swore to be a man of honor faithful to his family and to the obligations arising from his position. Every man at the hall followed the lord in taking their oaths.

The symbolism of the boar was important in Norse mythology in which the god Frey is given a boar. This golden-bristled boar, which darkness could never overtake, represented the sun for its bristles shone like the sun’s rays. In Norse folklore, the boar was also said to have first taught man the art of plowing and thus also became symbolic of the golden grain. (6)

Having shed its pagan past, the boar still makes a fitting symbol for Christmas since it represents light and wheat, which are fulfilled in the Babe of Bethlehem Who is the Sun of Justice and the Bread of Life.

Christmas fowl

Fowl was also traditionally served in many places, because in the Middle Ages Christmas gifts and payments were made in the form of live fowl that would be fattened on raisins and milk. (7)

A distinguished lady carries in the peacock;

below, an assorment of festive Christmas meats

The beautifully arranged peacock was first skinned, stuffed with sweet spices and roasted, and then duly decorated so that the marvelous green, blue and purple feathers splayed out in colorful fanfare. (8)

So cherished were peacock feathers that they were even used to adorn churches in Christmas. Thus this glorious bird that symbolized the Resurrection and immortality was made to pay homage to the Infant King whose birth brought hope for eternal life.

In Sweden and Denmark, a fat goose was served in every home from the King’s palace to the peasant’s cottage. Many Austrians and Germans also served goose, and Provençal families ate goose in honor of the goose that was said to have greeted the Three Wise Men with his quacking when they approached the Christ Child. (9)

Ever since the discovery of America in the 16th century and the introduction of the turkey to the Old World, turkey has become a popular feature of the Christmas meal in many areas of Europe, including Spain and France.

So prized was this fowl from the New World that it was called the “monarch of the Christmas table” in the 18thcentury. The Spaniards traditionally stuffed their turkeys with sausage, bacon or ham, olive oil, garlic, onions, mushrooms, chestnuts or pine nuts and dried or fresh fruit, the stuffing varying from region to region. (10)

The traditional Mexican Christmas includes buñuelos (fritters), roast turkey & tamales; a doll figure in the Rosca de Reyes bread symbolized Christ

Other special meat dishes graced the table in different lands. In many British homes, roast beef was served instead of goose. In Galicia, Spain, the center of the meal was a suckling pig or a meat pie, while in the rural parts of Aragon a dish of lamb and chicken held the place of honor at the table.

Suckling pig also crowned the feast in Argentina and Serbia. Hare, venison or other game meat was popular amongst the Dutch and Belgians.

In Luxembourg, Austria and other Germanic lands, families feasted on sausages, while the French Canadians enjoyed a richly spiced meat pie called Tourtière.

A ceremonial royal French Christmas banquet

Country homes enjoy more simple repasts, but in the homes of the wealthy and bourgeoise families in cities, there are always multiple courses often including pâté, seafood, truffles and large birds garnished splendidly with symbols of Christmas. (12)

The Christmas meals of the past were very solemn and sacral, even in peasant homes. Our Christmas meals can also be graced with the sacrality of the past if we follow the old ways of ceremony and seriousness, and leave behind the banal and worldly ways of modern Christmas celebrations. Then, our earthly feast will fill our souls with a spiritual joy reminiscent of the joy of the Saints in Heaven.

Continued

Entrance of the Christmas Boar’s Head

- https://www.marvellous-provence.com/arts-and-traditions/traditions/christmas-in-provence/christmas-foods

- Steve Roud, The English Year (Penguin Books: 2006), p. 402.

- Lee Wyndham, Holidays in Scandinavia (Champaign, Illinois: Garrard Publishing Company, 1975), p. 78.

- Sigrid Unset, Happy Times in Norway (London: Wyman & Sons Ltd., 1943), p. 23.

- https://www.thebookofdays.com/months/dec/25a.htm

- Mary P. Pringle and Clara A. Urann, Yule-tide in Many Lands (Boston: Lothrop Lee and Shepard Co., 1916), pp. 18-39.

- Ann Ball, Catholic Traditions in Cooking (Huntington, Indiana: Our Sunday Visitor, 1993), p. 14.

- Mary P. Pringle and Clara A. Urann, Yule-tide in Many Lands (Boston: Lothrop Lee and Shepard Co., 1916), pp. 40-41.

- Dorothy Gladys Spicer, Festivals of Western Europe (New York: The H. W. Wilson Company, 1958), p. 62.

- Christmas in Spain (Chicago, Illinois: World Book-Childcraft International, 1983), p. 11.

- Ball, Catholic Traditions in Cooking, p. 17.

- Christmas in France (Chicago: World-Book-Childcraft International, 1980), pp. 22-27.

Posted December 20, 2024

______________________

______________________

|

|

|

|

|

|