Most of the teachings of Catholic Morals refer to the mentioned first and second phases. St. Augustine and other Church Fathers, as well as St. Thomas Aquinas and medieval Church Doctors, only knew the wars of the first phase.

Main principle for just war

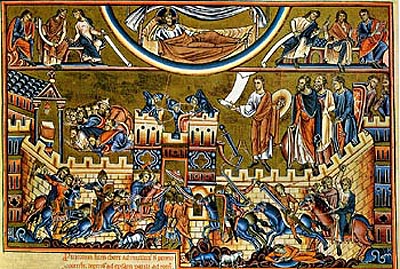

Doctors of the Church (middle right) setting out moral laws to govern the war (below), with God (top center) majestically watching over all |

St. Robert Bellarmine, Fr. Francisco Suarez, S.J., and St. Alphonsus of Ligouri were acquainted with the second phase. Their doctrine on war remained essentially the same as that which governed the previous phase. Here is a resume of St. Robert Bellarmine’s teaching:

“Just as natural law permits an individual to return, even by violent means, an unjust aggression against his life, his fortune, or his honor, for a stronger reason the same is permitted to a nation, which constitutes a political body, and forms a moral and public person. The head of this nation not only has the right but also the duty to use this means for the interest of the common good, for which he is responsible. This right and duty extends not only to the strictly defensive war, but also to the offensive war, when it is necessary …. [in face of] a real danger.” (1)

War and charity

Even if the war does not violate the virtue of justice, doesn’t it go against the virtue of charity? St. Robert Bellarmine also answered this question:

“One cannot suppose that God, Who is the supreme Author and Legislator of nature, would have granted to societies and individuals the right of self-defense – i.e., for societies the right to wage war – and by another law, such as the law of charity, would have always forbidden the waging of war. If this were the case, the right to wage war would be an useless and ridiculous right repugnant to Divine Wisdom. It would have been, as well, a flagrant contradiction between two Commandments of the Decalogue, one permitting and another forbidding the same thing, which also would contradict the wisdom of the Divine Legislator. Therefore, one can affirm as an a priori and secure truth that war, when it is just – that is, legitimate by natural law – cannot at the same time and by its own nature (ex natura sua) be illegitimate with regard to the law of charity. If in some cases the law of charity is opposed to the exercise of this right [to wage war], this is so only in some particular aspects (per accidens), and not in a general way.” (2)

War and social evils

What about the different social and economic evils that result from a war? T. Ortolan, a renowned pre-Vatican II moral theologian, summarized the teachings of many Saints and Doctors:

“Those who have the sovereign power in a nation are not obliged to abstain from a legitimate war, except when the pre-estimated resultant evils to the neighbor are without just proportion to the cause of the legitimate war. One should apply to the war the considerations that theologians have set forth about the foreseen side effect. When an action, legitimate per se, can have a double effect – one good and one bad – to carry it out, the reason for the action must be graver than the evil that can result from it, even if such evil is not voluntarily intended. This is why good princes …. only decide to go to war when they are obliged by an imperative necessity, and after the other means have been attempted and found futile.” (3)

Reasons for the just war

Theologians have elaborated moral reasons that legitimate a war:

“The reasons that can legitimize an offensive war generally relate to a grave insult received. Those that the authors point out are the following: to oblige the obedience of revolted subjects, to recover a lost province or city, to avenge a grave insult made to the head of the country, to punish another nation for the aid it gave to an unjust enemy, to chastise those who violated treatises, etc. It is easy to realize that wars of this genre, apparently offensive, are actually defensive.” (4)

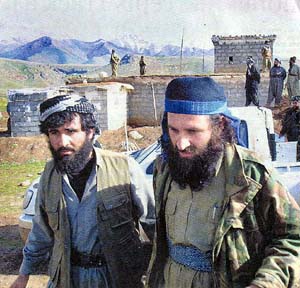

Terrorists at the training center of Ansar al Islam in North Iraq are taken away - L.A. Times, April 28, 2003 |

Another motive to justify a war is “to punish the actions of enemies who would have remained audacious and unrestrained in their bad purposes if they were not punished.” (5)

Both of these reasons, in my opinion, apply to the recent war with Iraq. As I explained in another article, this war was objectively a war against terrorism, the same international Islamic terrorism that attacked the United States and is supported and promoted by many Muslim countries, including Iraq. Was Iraq really supporting international terrorism? Yes, it supported it in the far past; likewise it supported it in the near past, as became evident when US and Kurd "forces have attacked and destroyed a massive terrorist facility," the international terrorist training center of Ansar al Islam in North Iraq on March 28, 2003. (6)

Why was the decision made to attack Iraq first, since Iran and Syria are known to give greater support to terrorism? Since the three countries all support terrorism, the order of attack against the enemy would not be so important. Such a preference probably depended on strategic military goals that were not revealed to the public.

Ecclesiastical law on war

Gratian’s Decretum is the most complete collection of Canon Law and Catholic legislative principles until the 12th Century, and has remained an important source for many commentaries on Canon Law. I present a summary based on Ortolan regarding different questions of Part 2, Cause 23, which deals with war:

“Question 1: Is the military profession sinful? The answer is negative, and the negation is supported by numerous arguments. It is demonstrated that the military life …. can be most praiseworthy: ‘Men can please God in the military profession. For example, God great testimony of this to David, who was sanctioned in the exercise of arms …..’

“Question 2 deals with the causes of the just war. The war has to be authorized by legitimately established public authority …. Ruses and ambushes are permitted in war. This is proved by examples in the Old Testament, in which God Himself counseled or ordered ruses in warfare.

“Question 3 examines whether the insult or damage caused to allies is sufficient cause for war. St. Ambrose answered this question with an energetic argument: ‘If the allies of a offended party do not repel the injury given when they are able to do so, they become like the one who made it.” And further: ‘Whosoever should stop the impious behavior and does not do so, in fact nourishes it ….” (7)

“Question 4 deals with public punishment. While at times, for the sake of peace one should tolerate evil persons, at other times one must correct them, and even exclude them from society if there is no hope of their amendment. This way of acting does not violate charity or peace, but is for the good of the entire society. Charity orders us to place the common good before that of the individual…. ‘The medicine of severity is what forces the evil to be good. Mercy can be charitable, but it can also be unjust. The established powers have the obligation to stop a disturbance to the public order ….

“Following the example of Christ, one can use violence to move evil men toward the good. This is not cruelty, but love. Far from being a fault, it is a way to soothe the just wrath of Almighty God. The faith of the combatants prepares for the victory; while delay in punishing evil attracts the ire of God.

“Question 5 teaches when homicide is permitted. In a just war those who kill the enemies do not break the Fifth Commandment: ‘The soldier who kills an enemy in obeying the legitimate authority is not guilty of homicide.’ …. Kings [the authorities] are obliged to make it impossible for evil persons to harm the good.” (8)

These are some of the superb anti-liberal precepts that inspired Canon Law during the centuries before and after Gratian’s compilation.

How do these principles apply to the present situation? The application is more or less intuitive. For example, let me take only the extraordinary norm taught by St. Ambrose “Whosoever should stop the impious behavior and does not do so, in fact nourishes it.” Who cannot see that international Islamic terrorism is being supported by the principles of Jihad preached by an influential and growing wing of the Muslim confession? Also, who does not realize that these same principles are followed by many countries that consequently finance and host terrorism? If, therefore, the West does not stop this “impious behavior” when it is able to do so, it becomes an accomplice to the crime.

The moral duty of the soldier and the commander in war

French soldiers leaving for war in the late 19th century |

After Vatican II, when the so-called objection of conscience was introduced to sabotage military service and participation in war (Gaudium et spes, 79c), it became frequent for progressivist religious authorities to present war as a problem of conscience for the soldier.

According to this thinking, if the solder is not completely convinced of the justice of the war, he should be dispensed from combat. This counsel is not consistent with Catholic traditional teaching on the topic. St. Alphonsus of Ligouri, who is considered one of the most reputable Church moralists of all times, taught this principle regarding the obedience due from soldiers and commanders:

“One can ask if a soldier can fight when he has doubts about the justice of the war. In reply, I should distinguish: if he is a subordinate [i.e., if he is a soldier or a subordinate officer] he not only can, but he must fight, according to the sentence commonly admitted by commentators on the inspired text of St. Augustine In can. Quid culpatur, dist. 23, q. 1. In it he affirms that the soldier can fight if he is uncertain whether the war is unjust: ‘If it is not certain, [that the war is against the precept of God]’, are the words of the Fathers. The reason is that the subject is obliged to obey when he does not have the certainty of sin, as I taught in my Treatise I, n. 18.

“If he is not a subordinate [i.e., if he is a general commander], however, he cannot wage war unless he is certain of its justice. Because no one can collaborate with depriving another of what belongs to him, unless it is certain that he possesses it unjustly.” (9)

Therefore, it is an obligation for any Catholic soldier in these conditions to fight for his country in a war; a fortiori, a citizen is obliged to enlist in military service, which provides the necessary training for war.

Objections to war taken from the Holy Scriptures

Theologians also have answered many of the objections to war taken from Holy Scriptures. I summarize the most important:

Statues on Reims Cathedral: Melchisedech offers the Host to Abraham, dressed as 13th-century knight |

First objection – God reserved to Solomon, son of David, the glory of building the Temple, and excluded his father from this work because he was a man of war, having shed blood (1 Par 17: 4; 28:3).

First response – There is no condemnation of war in that episode, but only a special measure taken against David because of his unjust homicide of Urias and the respect due to the Temple of God. (10)

Second objection – The text of the Gospel “But I say to you, not to resist evil: but if any one strikes thee on thy right cheek, turn to him the other also” (Matt 5: 39) invites us to avoid war.

Second response – This text should be understood as regarding personal revenge. It does not apply either to the just war for the defense of a State or to the safeguarding of its interests threatened by the malice of someone else. (11)

Third objection – When Our Lord ordered St. Peter to return his sword to the sheath, since the ones who take up the sword shall perish with it (Matt 26: 52; Jo 18: 11), He was indicating that war is bad.

Third response – In this case Our Lord was not referring to war in general, but to a particular action of St. Peter, who was raising an obstacle for His divine mission to be accomplished. (12)

Fourth objection – The text of St. Paul, “Revenge not yourselves, my dearly beloved: but give place to wrath, for it is written: Revenge is mine, I will repay, saith the Lord” (Matt 12: 19,) and also the text, “Render to no man evil for evil: providing things good, not only in the sight of God, but also in the sight of all men” (Matt 12: 17), prove that we should not wage war.

Fourth response – In these texts and in other similar ones, St. Paul was not speaking about the legitimate public authority, which has the right and the duty to cut off enemies that harm the whole society. (13) This right and duty is admitted by St. Paul himself when he spoke about the public authority: “For he is the minister of God to thee for good. But if thou do that which is evil, fear: for he beareth not the sword in vain. For he is the minister of God: and avenger to execute wrath upon him that doth evil” (Matt 12: 4). This power, which the head of State can and must exercise against evil, refers to not only internal but also external enemies of the State, as commentators on this passage have noted.

The next article will show the consistency of the position of Pius XII with the traditional teaching of the Church when he dealt with atomic weapons. It will also demonstrate how John XXIII and Paul VI changed this doctrine to introduce a pacisfist utopia.

Posted June 1, 2003

1. St. Robert Bellarmine, II Controversia generalis. De membris Ecclesiae militantis, 1. III, De laicis, chap. 14, Opera omnia, 8, Naples, 1872, vol. 2, p. 327, apud T. Ortolan, Dictionnaire de Théologie Catholique, entry “Guerre,” vol. 6, col. 1908. To confirm this sentence, see St. Augustine, Epistola 5 ad Marcellinum, c. 2, n. 15, PL 33, col. 531-2, Sermo 82 de verba Domini, 19, PL 39, col. 1904, In Pentateuch, 1. VI, q. 10, PL 34, col. 181; Epistola 189 ad Bonifacium, n. 6, PL 33, col. 856, Contra Faustum, 1, 22, chap. 75, 78, PL 42, col. 448, 450-1; St. John Chrysostom, Homilia in Joannem, PG 59, col. 35; St. Athanasius, Epistola ad Amunem, PG 26, col. 1173; St. Gregory Nazianzen, Oratio 3 de pace, PG 35, col. 924; St. Gregory the Great, Epistolae 1 and 84-85 ad Gennadium, PL 77, col. 528-9; St. Gregory of Tours, Historia, 1, 5, chap. 1, PL 71, col. 515; St. Leo IV, Epistola. ad exercitum Francorum, PL 115, col. 656-7; St. Bernard, Sermo ad milites, chap. 3, PL 182, col. 924; St. Leo IX, PL 215, col. 107, apud Ortolan ibid., col. 1912-4.

2. St. Robert Bellarmine, De laicis, chap 14, Opera omnia, vol. 2, p. 330, apud T. Ortolan, “Guerre,” col. 1909.

3. St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, II, II, q. 40, a.1; Francisco Suarez, De charitate, disp. 13, sec. 1, nn. 1, 4, 5; sec. 4, 6, Opera omnia, vol. 12, pp. 737, 743-5, 749-51; St. Robert Bellarmine, 1, III, De laicis, chap. 15, Opera omnia, vol. 2, p. 331; Schmalzgrueber, Jus ecclesiasticum universum, secundum quinque libros Decretalium, 1, I, tit. 34, § 1, De bello, nn. 2-4, 12 (Rome, 1843-1845), vol. 1b, p. 276-8; Zigliara, Ethica et jus naturae, 1, III, chap. 2, a.1, § 2, nn. 735-7 (Fribourg-in-Brisgau, 1900), vol. 2, pp. 788-90, apud Ortolan, ibid.

4. Laymann, Theologia moralis, 1. II, tr. 3, chap. 12, n. 6 (Venise, 1769); Schmalzgrueber, Jus ecclesiasticum universum, 1. I, tit. 34, § 1, n. 7, tit. 1b, p. 279, apud Ortolan, ibid.

5. Suarez, De charitate, disp. 13, sec. 4, n.5, Opera omnia, vol.12, p. 744; St. Alphonse de Ligouri, Theologia moralis, 1. III, chap. 1, dub. 5, a. 5, nn. 402-4 (Rome: Ed. Gaudé, 1905-1912), vol. 1, p. 659, apud Ortolan, ibid.

6. Tommy Franks, Press interview, Headquarters United States Central Command - Internet News Release, March 30, 2003; Los Angeles Times,"Guerillas Routed in U.S.-Kurd Assault," March 29, 2003; “Road to Ansar Began in Italy,", April 28, 2003.

7. St. Ambrose, De officiis, 1, I, chap. 36.

8. Gratian, The Treatise on Laws (or Decretum), apud Ortolan, ibid., col. 1917-8.

9. St. Alphonsus of Ligouri, Homo apostolicus, Tract. 8, De quinto praecepto, chap. 3, De bello, n. 31 (Paris: Facultatis Theologiae Bibliopolam, 1832), vol. 1, p. 293.

10. Suarez, De charitate, disp. 13, De bello, sec. 1, n. 3, Opera omnia, vol. 12, p. 738, apud Ortolan, ibid., cols. 1910-1.

11. St. Robert Bellarmine, II Controversia generalis, De membris Ecclesiae militantis, 1. III, De laicis, chap. 14, Opera omnia, vol. 2, p. 328, apud Ortolan, ibid., cols. 1911.

12. St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa theologiae, II, II, q. 40, a. 1, ad 1st; Suarez, De charitate, disp. 13, De bello, sec. 1, n. 3, Opera omnia, vol. 12, p. 738; St. Robert Bellarmine, II Controversia generalis, De membris Ecclesiae militantis, 1. III, De laicis, chap. 14, Opera omnia, vol. 2, p. 328, apud Ortolan, ibid..

13. Suarez, De charitate, disp. 13, sec. 4, n. 6, vol. 12, p. 744-6.

14. Ibid., p. 744.

|

This argument is developed in Guimarães’ book War, Just War

|