|

The Saint of the Day

St. Dositheus – February 23

Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira

Biographical selection:

This saint lived in the early part of the Middle Ages (c. 530). He lived a worldly, carefree life paying no attention to anything of the Catholic Faith. After hearing many stories of Jerusalem, he became curious to visit it, and traveled there with friends.

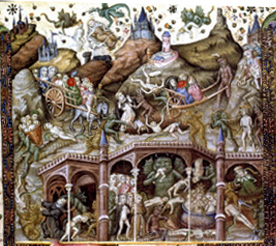

An image of souls suffering the torments of Hell from a French Book of Hours

|

In Gethsemane he saw a painting of condemned souls being tormented in Hell, which struck him with great force, but he did not understand its full meaning. A lady of extraordinary beauty and majesty approached him and explained to him the significance of the Last Judgment, Heaven and Hell. Impressed, he asked the lady what to do not to be condemned. She answered: You must flee sin and pray. And she disappeared.

Her counsel changed Dositheus’ life. Although mocked by his friends, he followed her advice, and sought out a monastery in the desert directed by St. Seridon and asked to be admitted. The Abbot put him under the care of St. Dorotheus, who became his master. Given that Dositheus was not a robust man, St. Dorotheus dispensed the new novice from the austerities of the monastery, and trained him instead to sacrifice his will. Gradually, he taught Dositheus how to fast and control his lively temper and oscillating moods.

After some time, he assigned Dositheus to the infirmary. Often he would become irritated with his patients, and then fall into deep scruples, but his master would teach him patience and confidence, and he would take up his work once again.

A new monk receives the tonsure upon entering the monastery

|

Once at the hospice, he proclaimed exuberantly to his master, “Look how well I have made the beds!” St. Dorotheus told him: “You are an excellent bed-maker, no doubt, but I fear not much of a monk.” When Dositheus needed new clothing, Dorotheus ordered him to sew them; then when they were ready, he was told to give them to other monks and to make a new set for himself.

St. Dositheus liked to read the Scripture and analyze the obscure meaning of its words, and at times he would make an interpretation that even the best experts had missed. Whenever he had a doubt, he would go to his superior to ask the solution. St. Dorotheus would reprimand him for his curiosity and leave his questions unanswered. One day, instead of receiving him, he sent him to the Abbot, St. Seridon. The Abbot, forewarned that he was coming, looked severely at the disciple and told him: “It is not for you, ignorant as you are, to speak about such elevated things. Instead, reflect upon your sins and the worldly life that you lived.” Then he sent him away, after slapping him on the face. St. Dositheus tranquilly returned to his cell.

A monk in contemplation on his deathbed

Historia Anglorum, 1250

|

After five years of the novitiate, the saint became gravely sick with a sickness of the lungs. Because of his weakness, he was confined to his bed, where he suffered greatly. During a visit of St. Dorotheus, he asked, “My father, give me the order to die, because I can no longer bear the pain.”

“Have a little more patience, my son,” his master answered.

Some days later, he asked again: “My father, I can bear to live no longer.”

This time his superior said: “Then, go in peace, my dear son, and present yourself before the throne of the Holy Trinity.”

According to the Lives of the Fathers of the Desert [Vita Patrum], this blessed son of obedience slept the sleep of the just, wrapped in the bosom of this virtue, which was like a mother for him on his path of perfection.

Comments of Prof. Plinio:

Reading this excerpt a young person could well think that this man, Dositheus, was a soft and fearful man. Indeed, he had all the appearances of being a fearful man. He was intimidated by that painting of Hell that he was looking at. Then, after a beautiful lady explained its meaning to him, he ran off to a monastery; he literally fled to it. In the monastery, he found a little cocoon where he would take care of the sick monks. This job seems to be a soft job. One can imagine him entering the infirmary with all sick people in their beds, saying: “Good morning, my sick friends!” They answer: “Good morning, Dositheus!” Everything goes smoothly and easily: he gives a little medicine to this one, talks a bit to that one, comments on the soup that is coming for them, etc.

It is true that those superiors seem somewhat rude, especially in that episode where the Abbot slapped Dositheus in the face. But overall they were good men, who acted this way to break his will and prepare him to die well. Which is what he did; he even asked permission to die. So, he went to Heaven and the story is finished.

This is how I think many young persons today might interpret this selection. Are they wrong in thinking this? If so, why?

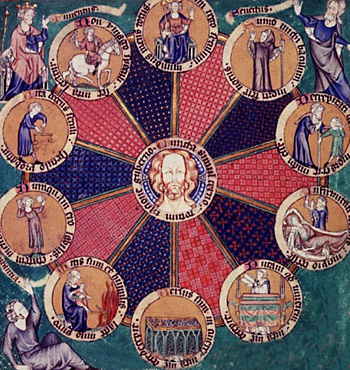

The key to understand the life of St. Dositheus is his contemplation of Scripture

|

In fact, they are wrong. This saint was not a coward, and his life was not easy, or he could not be considered a hero by the Church. It is the way the lives of many saints are written that generate this kind of thinking. There is nothing overtly wrong with this selection, for example, except that the grandeur and the heroism of the saint are downplayed in such a way that everything seems quite commonplace. So, unless the person can read between the lines and find them, he will get the wrong idea about the saint.

For example, in this selection it is said in passing that St. Dositheus liked to read Holy Scriptures, and would at times make an interpretation that was unique. In my opinion, here is the key to understand the soul of St. Dositheus: here is the key to his religious life. Everything else can be explained in relation to this point. How does this point illuminate everything else?

For a person to interpret Holy Scriptures well, finding a meaning that does not even occur to the exegetes who are experienced masters in Scriptures, he needs a special grace, which is a particular charisma. To have this charisma, the person must have reached a high degree in the virtue of contemplation. This is to say that the person must be very profound, very reflective, always turned toward the highest considerations of the cause of God. So, this person is turned principally to think about the great eternal truths, and not the little things he does in his daily life.

Applying this to St. Dositheus, we see that even before converting, he already had some of this spirit when he was trying to interpret that painting of Hell, but could not understand everything. Probably his soul was already seeking something of the deepest meaning of that painting. Then, Our Lady appeared to him, and explained what he did not understand, and placed in his soul a desire to enter a new life where he could better know and comprehend the Catholic truths. She also put in his soul a healthy fear of God to encourage him not to sin.

So, with these two sentiments, a first taste of this special grace of interpreting hidden truths and a fear of Hell, he was able to face the mockery of his friends, abandon all his earthly goods, and enter a life of contemplation. This is why he went to the monastery: to be a man of contemplation. With this background, we can understand how he would treat the sick, contemplating the deepest meaning of those illnesses for the body and for the soul. In the same way he would see the symbolism of the medicines. He would consider the penitential merit of the illness and, the pedagogical manner those sufferings were meant to form the characters of the sick monks to help them sanctify themselves, making each one more similar to God.

Therefore, St. Dosithesus would carry out the humblest chores in the infirmary, such as giving a medicine or changing the pillow on a sick bed, in an excellent way, always with a profundity of thinking that would unite him more to Our Lord Jesus Christ.

A medieval painting points to Christ as the center of a man's life through its Ten Ages, from birth to the coffin

|

Thus, the moral profile of this saint is not that of the foolish and cowardly young man that he appeared to be at first sight, but of a highly contemplative monk with the most elevated thoughts. His grandeur, his nobility, and the perfection of his life appear clearly under this light. His presence in the room of the hospice would be like a burning thurible spreading its incense everywhere and perfuming all those souls so that they would have a higher degree of love of God, and giving them desire to suffer, be generous and conform to the will of God.

This also explains his obedience. His superiors, who were also saints, understood their mission to form this monk and took everything from him that could remove him from God. This is why they would order him to do the opposite of what he was planning, often the opposite of what they themselves had previously ordered. When one is accustomed to give up his own will, he will instinctively ask what is the will of God.

A man with such a spirit of contemplation and such a spirit of obedience is a hero who can execute any kind of grand feat: he can take Jerusalem from the Moors, build a gothic cathedral, or die in the battlefield. St. Dositheus had the very essence of heroism, which is self-renunciation and an elevated degree of love of God.

Let us ask St. Dositheus to give us the grace of contemplation so that in all that we see or do, we can discern everything of the good God placed in it, and everything evil in it placed there by the Devil and the Revolution. Then, after discerning the evil, we should reject it to make the cause of Our Lady triumph.

| |

Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira |

|

The Saint of the Day features highlights from the lives of saints based on comments made by the late Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira. Following the example of St. John Bosco who used to make similar talks for the boys of his College, each evening it was Prof. Plinio’s custom to make a short commentary on the lives of the next day’s saint in a meeting for youth in order to encourage them in the practice of virtue and love for the Catholic Church. TIA thought that its readers could profit from these valuable commentaries.

The texts of both the biographical data and the comments come from personal notes taken by Atila S. Guimarães from 1964 to 1995. Given the fact that the source is a personal notebook, it is possible that at times the biographic notes transcribed here will not rigorously follow the original text read by Prof. Plinio. The commentaries have also been adapted and translated for TIA’s site.

|

Saint of the Day | Home | Books | CDs | Search | Contact Us | Donate

© 2002- Tradition in Action, Inc. All Rights Reserved

|

|

|