|

The Saint of the Day

St. Stephen, King of Hungary, September 2

Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira

Biographical selection:

The father of Stephen was the Magyar Duke Géza of Hungary. When Géza married Adelaide, sister of the Catholic Duke of Poland, he and many nobles received Baptism. None, however, but his son Stephen, who was age 10, took it seriously.

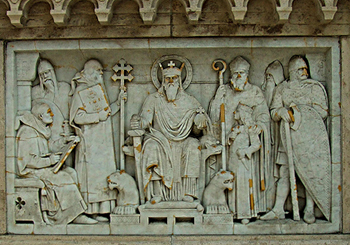

St. Stephen, the first King of Hungary

|

At age 20, Stephen married Giselle, sister of St. Henry II, the future Emperor of the Holy Roman-German Empire who became a great ally of St. Stephen in spreading the Catholic Faith. Two years later, in 997, he succeeded his father as the fourth Duke of the Magyars to be named since that fierce marauding people from the east had settled along the Danube borders.

To the piety and the zeal of an Apostle, St. Stephen added the courage of a warrior and a hero. In the instructions he wrote to his son, St. Amelric (Emeric, Americ or Americo), he noted that he had spent almost all his life in wars, extending his Catholic lands and repelling invasions of foreign nations.

Indeed, as soon as Stephen ascended to the throne, many nobles who both feared the rules of Stephen’s new Religion and wanted to keep the old pagan superstitions revolted against him. They burned the fields, killed Catholic nobles faithful to Stephen, and raised a siege around the city of Veszprem. Stephen gathered his troops and, with the help of his German allies, marched against them under the banners of St. Martin and St. George. Though inferior in number, he defeated the rebels and killed their leader Koppany. To thank God for the victory, he built a monastery in honor of St. Martin over the battlefield, called the Holy Hill.

Among many other benefits for the Church, he founded the archbishopric of Gran (Eztergom), with five dioceses under it, and later the archbishopric of Kalocsa, with three dioceses. He then sent his ambassador, the skilled St. Asteriscus, to Rome to ask the Pope to approve those foundations. He also requested the title of king. Pope Sylvester II wholeheartedly granted both wishes and sent Stephen the crown that became the Royal Crown of Hungary, known as the Crown of St. Stephen.

The same Prelate, St. Asteriscus, acting now as representative of the Pope, anointed Stephen and crowned him with great solemnity in the year 1001. Stephen established the see of his kingdom in the city of Alba Regalis.

The Monastery the King dedicated to St. Martin on the Holy Hill

|

In 1003 his pagan uncle Gyula, Prince of Transylvania, invaded his lands to depose him and take his lands. Stephen defeated him and incorporated his uncle’s territories under the Hungarian Crown. Soon afterwards, he crushed a revolt of one of his nobles who wanted to pay allegiance to the Emperor of Byzantium.

Next, he repelled an invasion of the Besso people from Bulgaria, defeating them and personally killing their leader. Many Bulgarian chieftains asked the King for permission to peacefully cross the borders into Hungary. St. Stephen granted their request. When they entered Hungary, however, Magyar bandits set about robbing and killing most of them. Stephen condemned the guilty outlaws and ordered them to be hung in pairs and exposed along the roads leading to Bulgaria, so that all would know that foreigners were welcome in Hungary.

St. Stephen always had a special devotion to Our Lady. In a personal vow, he placed his person and his kingdom under her protection. When the Hungarian people referred to the Mother of God, they did not call her Mary but the Great Lady. At the mere sound of these words, they would bend their heads and knees.

The King-Saint had always asked Our Lady the favor to die on August 15, the day of her Assumption into Heaven. His wish was granted. Before expiring, he raised his eyes to Heaven and said: “Queen of Heaven, Co-Redeemer of the world, it is to you as patroness that I deliver Holy Mother Church in Hungary with her Bishops and Clergy, and the Kingdom with its magnates and people. After receiving the Holy Eucharist and Extreme Unction, he delivered his soul to God on August 15, 1038

Comments of Prof. Plinio:

St. Stephen was a saint whose conversion brought the Hungarian nation to the Church. He was, therefore, the Clovis of Hungary, but with this difference: Clovis converted but was far from being a saint, while St. Stephen became a true saint. The direct descendants of Clovis were not saints, but the son of St. Stephen, Amelric, became a saint. We don’t realize that the name Americo in Latin languages honors St. Amelric, the son of St. Stephen. Our Continent America took its name from Americo Vespuccio, but Vespuccio was named Americo in honor of St. Amelric, given his great fame in that epoch.

The Holy Crown of St. Stephen

|

This selection on the life of St. Stephen shows us one of these marvels of the Catholic Church which can never be stressed enough. People talk against this or that aspect of the Catholic Church because they refuse to see the totality of her virtues. In the totality of her virtues she is more than in each one considered individually. In this regard, the Church is similar to Creation. Scripture tells us that God contemplated His works and saw that each was good, but that the ensemble was excellent.

In the life of St. Stephen, a modern Catholic with some effeminate sentiments would say that he was a cruel man, always engaged in fighting and destroying his enemies, taking possession of the lands of his uncle, killing a leader of the Bossi with his own hands, hanging the insubordinate Magyars who robbed people he had welcomed into his kingdom. Such a critic would like to have a St. Stephen who would only forgive, always offer the other cheek to be slapped, and flee any confrontation in defense of the Catholic Faith.

The Catholic Church practices all the virtues: she shows both goodness toward the enemy, as well as combativeness. She has mercy for the guilty, but also justice. In the harmony of apparently opposite virtues, we find the whole physiognomy of the Church. This ensemble is nobler and more excellent than each one of the virtues. Let us not forget that when the Church canonized St. Stephen, she presented all the actions of his life as exemplary and to be imitated by all Catholics.

So, with this presupposition, let me make an apologia for St. Stephen’s action regarding the revolt of nobles against him.

St. Stephen with his Bishops and Knights, Budapest Cathedral

|

First, he was dealing with pagan semi-barbarians, many of them incapable of understanding any language other than force. The selection does not mention this, but he brought to Hungary many missionaries who tried by every persuasive means to convince those people of the truth of the Catholic Faith. They rejected the preaching and inflicted martyrdom on many of those missionaries. Therefore, those nobles who revolted against St. Stephen were enemies of the eternal salvation of the Hungarian people.

Second, those revolted nobles took up arms to depose St. Stephen from the throne he had just received from his father. Doing so, they also showed themselves to be enemies of the sovereignty of the Hungarian people, who had made him the legitimate successor to the throne.

Third, creating a situation of contestation and chaos inside the nation, those rebellious nobles were preventing the Hungarian people from realizing any real progress. To progress, a people needs peace to build its own civilization. Catholic Faith is par excellence what brings the natural order to its apex and propels a people to progress.

Therefore, those nobles, to keep Hungary in a condemnable state of paganism, wanted successively to extinguish the Faith, depose the legitimate heir to the throne and prevent the real development of the nation. The very future of Hungary was being decided in that fight. There is no question that St. Stephen had every right to fight these rebellious nobles and destroy them. It was perfectly fair.

Regarding his fight against the invasion of the Besso people, we see that the Bessi were also pagan. They invaded Hungary with the aim of overtaking it. In those times, the soul of an army was the king. He was not only a symbolic figure, but he was the actual leader of the battles. Often he was the best or one the best warriors of his army. So, it was common in medieval battles for two kings to fight each other like two champions.

Warrior kings were common in medieval times

|

Anyone who reads the Chanson de Roland sees that the battles were fought by antagonists who enjoyed a similar rank of nobility on both the Catholic and the Muslim sides. Each Catholic champion fought an enemy champion of the same level. I am not saying that it was always like this in the battles. I simply affirm that this was the ideal. So, according to the mentality of those times, where honor and nobility played a decisive role, nothing was more comprehensible than for a Catholic King to fight and kill a Pagan King with his own weapons.

His pagan uncle came from Transylvania to attack him and conquer his land. He counter-attacked, took his uncle prisoner, and incorporated his lands under his crown. This is what in law we call the right of conquest. If a nation has the firm purpose of destroying another nation, the latter has the just right of defense. And in order to prevent continuous threats from the former, the conquering nation has the right to take the former and assimilate its lands to its own nation. This was especially true in those times when those fierce peoples were still emerging from barbarianism.

Why did he act so energetically against those who violated the safe-conduct he gave to foreigners who wanted to establish themselves in Hungary? He did so because the bandits who committed that crime violated one of the most elementary rules of international law - hospitality. St. Stephen had given his word that those Bossi could enter Hungary as friends and launch their

lives there as loyal subjects. They believed in his word; they set aside their weapons and brought their families, gold and goods to begin a new life. We see that those people most probably would have converted to the Catholic Faith in their new land. Then, the bandits violated the word of the King by killing many of those peaceful immigrants after stealing their gold and goods. It was an infamy that had to be punished with death.

King St. Stephen of Hungary

|

This energy and strength applied to serve the Catholic cause were approved when the Church canonized St. Stephen. On the other hand, he was known for his mercy toward the weak and the poor, always protecting widows and orphans. He was magnanimous with the Clergy. Above all, he had an ardent devotion to Our Lady. He consecrated his life and Hungary to the Great Lady, as he used to call her.

So every aspect of the life of St. Stephen is highly commendable.

I close by insisting on the harmony of the opposite virtues that characterizes the Catholic spirit. St. Francis de Sales who was known for his gentleness and suavity, did all he could to assist the efforts of the Duke of Savoy to lead a crusade against the Calvinists of Geneva. Unfortunately, his troops were defeated. Today one can visit the wall where Catholic blood was shed in the past, shed by soldiers who had been encouraged to fight by the Doctor of suavity. Again, the harmony of opposite virtues.

In the liturgy Our Lord is called the Lamb of God because He was the model of meekness in His Passion. But Scripture also calls Him the Lion of Judah because he will come at the end of the world in glory and majesty to destroy the Antichrist and his cohorts and to judge the living and the dead.

Let us ask St. Stephen to give us the grace to understand and love those apparently opposed but actually complementary virtues we find in his life and in the Catholic Church.

| | Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira | |

The Saint of the Day features highlights from the lives of saints based on comments made by the late Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira. Following the example of St. John Bosco who used to make similar talks for the boys of his College, each evening it was Prof. Plinio’s custom to make a short commentary on the lives of the next day’s saint in a meeting for youth in order to encourage them in the practice of virtue and love for the Catholic Church. TIA thought that its readers could profit from these valuable commentaries.

The texts of both the biographical data and the comments come from personal notes taken by Atila S. Guimarães from 1964 to 1995. Given the fact that the source is a personal notebook, it is possible that at times the biographic notes transcribed here will not rigorously follow the original text read by Prof. Plinio. The commentaries have also been adapted and translated for TIA’s site.

|

Saint of the Day | Home | Books | CDs | Search | Contact Us | Donate

© 2002- Tradition in Action, Inc. All Rights Reserved

|

|

|