|

The Saint of the Day

St. William of Gellone or

St. William of Aquitaine – May 28

Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira

Biographical selection:

The Emperor Charlemagne had summoned to his court the good Duke William of Aquitaine (768-814), grandson of Charles Martel and one of his paladins and Twelve Peers, who were considered almost as kings in his Empire. William had defeated the Saracens in 20 campaigns. Wealthy, magnificent, surrounded by glory, he reigned in Toulouse, honored by the people, esteemed by the Emperor and loved by God.

Charlemagne led by an abbot, symbolizing his spiritual submission; between them is St. William |

When he arrived, the Emperor covered him with attention and praise. And, since in Charlemagne’s household each loved the other, all felt great joy at the arrival of that relative of the Emperor. Duke William, however, was anguished of heart. One day, trembling, he said to the Emperor:

“Lord Charles, my father, listen to your soldier. You know, Lord, how much I love you and how I have served you. You are dearer to me than life and light. I was at your side in battles and everywhere I faced danger for your person. I made my body a shield for you…

"But now, the time for battles has passed and I ask permission that henceforth I might serve my Eternal King. Therefore, my friend and my father, allow me to leave because long ago I made a vow to leave this world and enclose myself in the monastery that I built in the desert for the love of you.”

The good Emperor, surprised, moved his body and remained some moments without speaking. But finally, heaving a great sigh, he said:

“Duke William, you are breaking my heart… Certainly, if you had preferred a king or emperor to me, I would consider it an injury, and I would move the universe against that emperor because he had stolen Duke William from me. But I cannot prevent you from leaving my army to become a soldier of the King of Angels. I cannot do this. I give you my permission, then, to go. I ask but one thing of you: to accept a gift as a memory of my friendship.”

Having said this, he embraced Duke William around the neck and cried bitterly. Seeing the Emperor weeping, the Duke also melted in tears. But reassembling his strength, he said to the Emperor:

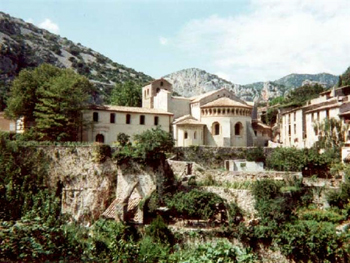

Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert, originally Gellone, the monastery William founded in 804 and entered in 806. |

“Your Highness should cease to weep, as should this servant of yours. If I had foreseen these tears, I confess that I would have run away without even greeting you. Now, my Lord, for the greater good of us both, send me to our common Lord, not with sadness, but with Christian joy. As for the treasures you have offered me, I thank you, but I wish to embrace the poverty of Our Lord Jesus Christ, and if I have chosen to leave all that belonged to me, how could I take what is yours?

“However, if you truly desire to offer to God something in my person, then I ask you for a part of the Holy Cross that you received in Jerusalem on that day that I accompanied you.”

And the good Emperor Charles, although he was very attached to that precious relic, immediately gave it to the good Duke William as a pledge of his perpetual friendship, more enduring than life and stronger than death.

Duke William entered the monastery in the year 806. Now a humble monk, the Duke, mounted on a donkey and clothed only in a simple tunic, would bring food to the workers in the fields of the Monastery of Gellone, which he had founded in 804.

He was canonized in 1066 and today is known as St. William of Gellone or St. William of Aquitaine (Louis Veuillot, Les Parfuns de Rome).

Comments of Prof. Plinio:

I suggest that we examine this magnificent excerpt in parts to take advantage of its details.

The Emperor Charlemagne had summoned to his court the good Duke William of Aquitaine, grandson of Charles Martel and one of his paladins and Twelve Peers, who were considered almost as kings in his Empire. William had defeated the Saracens in 20 campaigns. Wealthy, magnificent, surrounded by glory, he reigned in Toulouse, honored by the people, esteemed by the Emperor and loved by God.

St. William, shown with a helmet, armour and monk's habit, crushing the head of the Devil |

Duke William reigned in Toulouse, which has always been a great French city situated in a rich and important area. What were the circumstances of his reign in Toulouse? He was honored by the people; his was not the vulgar popularity of most of today’s politicians whom the people mock and make jokes about. He was honored, that is, treated with veneration and respect by the people.

So he was honored by the people and esteemed by the Emperor and loved by God. This is a perfect situation: respected by the people, esteemed by the Emperor and loved by God. It is a complete glory; there is nothing to add.

"Lord Charles, my father, listen to your soldier. You know, Lord, how much I love you and how I have served you. You are dearer to me than life and light. I was at your side in battles, and everywhere I faced danger for your person. I made my body a shield for you…"

He was, I believe, a cousin of Charlemagne and uses the expression Lord Charles, my father. It is very beautiful to see this simplicity along with such grandeur. The title of Lord when directed to Charlemagne assumes an extraordinary elevation, because he was the Emperor, Lord of the lords, the temporal Lord par excellence.

On the other hand, it is remarkable how Duke William speaks so affectionately – Lord Charles, my father, listen to your soldier. Nothing is more beautiful than at the moment he makes his plea than to say that he fought for him, risking his life for him: “I remind you now of all the dangers I suffered for you. Listen to me in the name of all sufferings I endured for you.” It is very beautiful and very balanced.

“You are dearer to me than life and light.” Why is it more appropriate to say this rather than simply, You are dearer to me than life? I believe it is because it gives the idea that the life he lived being close to Charlemagne was a luminous life, filled with the clarity of virtue and spiritual values.

“I was at your side in battles, and everywhere I faced danger for your person. I made my body a shield for you.” Here St. William presents his case to Charlemagne arguing with the eloquence of a great lawyer. He knew how to present his case superbly.

“But now, the time for battles has passed and I ask permission that henceforth I might serve my Eternal King. Therefore, my friend and my father, allow me to leave because long ago I made a vow to leave this world and enclose myself in the monastery that I built in the desert for the love of you.”

It seems that he built the Monastery of Gellone for the monks to pray for Charlemagne. Then, after having dedicated his life to Charlemagne, he will dedicate it to God in the Monastery he built through fidelity to the Emperor. You see that the whole description is brimming with noble sentiments that have practically disappeared today. It is something that has vanished.

The good Emperor, surprised, moved his body and remained some moments without speaking. But finally, heaving a great sigh, he said:

Charlemagne was voiceless because he was losing one of his best generals. Then, he gave his reply. You can imagine his voice filled with many inflections, like an organ when it is playing in full tone.

He is the hero of the Chanson de Guillaume, an early chanson de geste, and of several later sequels |

“Duke William, you are breaking my heart…” After the solemn speech of the Duke, Charlemagne begins with this simple comment. It is surprising, but very beautiful.

“Certainly, if you had preferred a king or emperor to me, I would consider it an injury, and I would move the universe against that emperor because he had stolen Duke William from me.”

This is an excellent way to praise Duke William: He was worth a world war.

“But I cannot prevent you from leaving my army to become a soldier of the King of Angels. I cannot do this.”

The Emperor fully understood what he was saying with the words the King of the Angels, because the Angels constitute the army of God. He cannot forbid the Duke to leave the army of men to enter the army of God. No one can do that. Not even Charlemagne.

“I give you my permission, then, to go. I ask but one thing of you: to accept a gift as a memory of my friendship.”

Having said this, he embraced Duke William around the neck and cried bitterly. Seeing the Emperor weeping, the Duke also melted in tears.

You see how noble this is. Charlemagne, a man who had conquered many peoples without fear or tears, wept at the hour of separating himself from a general who had helped him to conquer those peoples. The Duke also shed tears.

This scene is very manly and lacking any egoism. The egotist, seeing the Emperor cry, would be pleased. He would look at the others in the room and think: “Are you taking note of this? The Emperor is weeping for me. The Emperor recognizes my value, even though you do not.” The egotist would be incapable of shedding tears at this moment.

The medieval men used to weep a lot. Anyone who thinks that the medieval was a cold Calvinist is completely wrong. He had the courage to face sorrow and pain, but he was not ashamed of crying when tears were appropriate.

But reassembling his strength, he said to the Emperor: “Your Highness …” Here there is a small imprecision. At that time, the Emperor and Kings were not called Your Highness or Your Majesty because the title of majesty was reserved exclusively for God.

“Your Highness should cease to weep, as should this servant of yours. If I had foreseen these tears, I confess that I would have run away without even greeting you.”

He is not saying that he would not serve God to prevent Charlemagne from weeping. His position is different: “Whether this causes you suffering or not, I belong to God. But I would have avoided this scene that causes you such emotion in your old age. I would have simply fled to the monastery.”

“Now, my Lord, for the greater good of us both, send me to our common Lord, not with sadness, but with Christian joy.”

That is to say: “This is not a time to be sad. Send me to the One Who is as much your Lord as mine.”

St. William, now a monk, returning to the Monastery after bringing food and water to the workers |

“As for the treasures you have offered me, I thank you, but I wish to embrace the poverty of Our Lord Jesus Christ. And if I have chosen to leave all that belonged to me, how could I take what is yours? However, if you truly desire to offer to God something in my person, then I ask you for a part of the Holy Cross that you received in Jerusalem on that day that I accompanied you.”

Duke William only wants a piece of the Holy Cross as the payment for a whole life of battles and works. No treasures, just the Holy Cross.

And the good Emperor Charles, although he was very attached to that precious relic, immediately gave it to the good Duke William as a pledge of his perpetual friendship, more enduring than life and stronger than death.

The good Emperor and the good Duke William: What an atmosphere! What a situation! Then, the two separated and agreed that they would only meet again in Heaven. Human words no longer suffice; their goal is Heaven, God.

Now a humble monk, the Duke, mounted on a donkey and clothed only in a simple tunic, would bring food to the workers in the fields of the monastery of Gellone, which he had founded in 804.

I only note here that these workers were also mostly monks.

Today he is known as St. William of Gellone.

St. William of Gellone, pray for us. Make us like you. There is nothing else to say.

|

|

Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira | |

The Saint of the Day features highlights from the lives of saints based on comments made by the late Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira. Following the example of St. John Bosco who used to make similar talks for the boys of his College, each evening it was Prof. Plinio’s custom to make a short commentary on the lives of the next day’s saint in a meeting for youth in order to encourage them in the practice of virtue and love for the Catholic Church. TIA thought that its readers could profit from these valuable commentaries.

The texts of both the biographical data and the comments come from personal notes taken by Atila S. Guimarães from 1964 to 1995. Given the fact that the source is a personal notebook, it is possible that at times the biographic notes transcribed here will not rigorously follow the original text read by Prof. Plinio. The commentaries have also been adapted and translated for TIA’s site.

|

Saint of the Day | Home | Books | CDs | Search | Contact Us | Donate

© 2002- Tradition in Action, Inc. All Rights Reserved

|

|

|