|

The Saint of the Day

St. Leopold III of Austria – November 15

Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira

Biographical selection:

Leopold was born at Melk, Austria, in 1073. At the age of 23 he succeeded his father as Margrave of Austria. In 1106, Leopold married Agnes, the daughter of Emperor Henry IV, who bore him 18 children, 11 of whom survived childhood and became known for their virtues or great deeds.

At age 23 St. Leopold became Duke and ruled wisely for 40 years |

Amid that numerous family and the civil wars that divided Germany at that time, the pious Margrave of Austria maintained his States in peace during the 40 years he ruled them, being an example of all the virtues to his people. His wife closely followed him in his good works.

He added to the Catholic virtues a great courage and valor. On the two occasions that the Hungarians attacked his lands, he won brilliant victories. For these triumphs he received the cognomen Leopold the Brave.

Otto, his fifth son, entered the Cistercian Order, attracted by the virtues of St. Bernard. His father, filled with joy, ordered the construction of the Abbey of Heilligenkreuz (Holy Cross) close to Vienna and gave it to the Order.

After a life celebrated for its sanctity and wisdom throughout Germany, he died in one of the three monasteries he founded on November 15, 1136. He was canonized by Pope Innocent VIII in 1486.

Comments of Prof. Plinio:

There are several interesting notes in this brief summary of the life of St. Leopold.

St. Leopold III leading his troops at the siege of Regensburg |

First, this is, like so many others, a practically unknown life. You see that he was a sovereign, a head of the Austrian State. He was a sovereign who was a duke, but the Dukes of Austria at that time had a status similar to a king. There is a long-standing tendency to downplay and hide from Catholics the saints who practiced virtues that sentimental piety cannot deform, such as the virtue of wisdom.

This sentimental piety does not appreciate the virtue of wisdom and tends to begrudge its value. It insinuates that Catholic virtue forms men who are very simple and a little dim-witted. The result is that St. Thomas Aquinas is a saint who is seldom venerated as a saint. It is rare to find a church or a cathedral with his name or processions honoring him because St. Thomas is an expression of wisdom.

This piety also projects the idea that a Catholic is not only a bit simple, but also fearful. Based on that premise, this school of sentimental piety tries to put into the shadows all the saints who were courageous. Can you imagine how magnificent it would be to have a church or a cathedral dedicated to St. Leopold the Brave with everyone praying to him? To have people saying: “St. Leopold the Brave, give us your valor to face our enemies.”

You can imagine an altar with a statue of St. Leopold in full armor and a sword in hand, advancing and shouting against his enemies during his fight with the Hungarians. But it is difficult to find such a portrayal. You see altars with saints who were not sentimental persons, but who are nonetheless distorted by that school of sentimental piety to hide the virtues it does not like.

Another point is that this kind of sentimental piety is very egalitarian; it is friend of Christian Democracy. But it has a horror of the saints who were great in the temporal sphere. It will glorify a saint who was king and abandoned his crown to enter the religious life, but ignores one who kept his crown and fought his enemies.

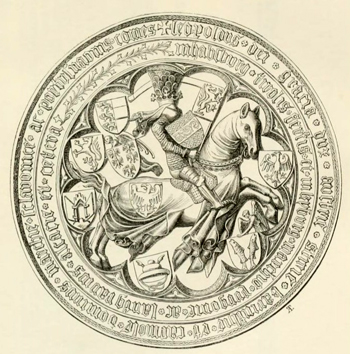

The seal of Leopold III displays him as a knight entering battle |

Doing this, it implies that it is not admirable to govern a State, it is not dignified to enter politics, it is not Catholic to go to a war. The only activities presented as laudable are to pray and to flee the world. In the world it admits only two categories: to be a scoundrel or to be a sacristan. This is the general view of this school of sentimental piety.

A man who reigned for 40 years and was a saint, who truly governed his people with wisdom, is too great a shock for such sentimental piety. He is relegated to the gallery of retired saints. Paul VI created the category of banned saints, but before that we had the retired saints who were put on the sidelines by those imbued with sentimental piety.

In his studies on the Middle Ages, Prof. Fernando Furquim points out the large number of feudal lords who were saints and were also disregarded. These are the ones whom we tend to adopt for our own calendar of saints, ones who represent the forgotten truths of the current calendar of saints. It is the necessary complement to the current calendar.

Another point of interest that the great figure of St. Leopold offers us is that he was married to the Duchess Agnes. This Duchess was the daughter of one of the worst persecutors of the Church, Emperor Henry IV of the Sacred Roman German Empire.

Henry IV was that sacrilegious and blasphemous Emperor who was forced to humiliate himself before Pope St. Gregory VII in Canossa. He spent three days and three nights in the snow awaiting the pardon of the Pope. Finally, the Pope forgave him, but afterwards Henry abused that papal pardon.

You can see how things were in the Middle Ages. It was possible for a saintly man to marry the daughter of a reprobate like Henry IV, a woman who was nonetheless a very good and worthy spouse. The explanation is that at that time sin had much less energy, much less capacity of expansion. Even when sin dominated a person to his depths, as in the case of Henry IV – one of the most infamous men in History – the irradiation of his sinfulness touched those around him much less, or even not at all. For this reason, even in the closest circles of this reprobate, it was possible to find a princess who was exemplary.

You also see the patriarchal figure of the good Margrave and his good wife who wisely governed their people for 40 years. Whoever is familiar with European literature can understand the good faith of the European peasant of that time: He was innocent, joyful, tranquil, confident, rosy and, when he smiled, there were two little dimples in his cheeks; above all I am referring to the Austrian and Bavarian peasant of the area where St. Leopold ruled.

Those peasants were the children of a long tradition of innocence. And the good Duke and the good Duchess ruled according to the good laws of the Holy Roman Church with a patriarchal wisdom. Of this ensemble of goodness today’s man has almost no notion because we live in a bad world.

The Abbey of Heilligenkreuz built by St. Leopold III,

below, the cloisters there today

|

Today, at the least the good are aware that we live in a very bad world. In this era of the triumph of the Revolution we have to have a suspicious mindset. But in an era when the Counter-Revolution was triumphant, there was a kind of mutual confidence and solidarity that made it normal for one to do good for others out of love of God. The youth of today cannot even imagine such a world, but things were this way then.

A bit of this good can be found in the scenario of the good Duke married to the good Duchess governing his people, who live in a country with snow covered peaks in the winter and intense green grass in the summer and little field flowers blooming among the cattle, with the peasants living in small cheerful chalets. All this charming goodness gives us an idea of an earthly paradise.

This man had a son who, following St. Bernard, became a Cistercian monk. St. Leopold was so pleased that he built an abbey to thank God for the vocation of his son. But he also understood that his vocation was different. He did not want to be Cistercian; he wanted to serve God by virtuously governing the people, and at this he excelled his whole life.

These are the more remarkable traits of the life of St. Leopold the Brave.

Let us close by expressing our desire that, in the Reign of Mary, parallel to the churches built in honor of many known saints, there will be also churches in honor of St. Leopold the Brave and other forgotten saints with similar lives. These churches would make all Catholics understand and love the ensemble of Catholic virtues. In this way we would have more luminous aspects of the Catholic spirit shining before the eyes of all peoples.

|

|

Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira | |

The Saint of the Day features highlights from the lives of saints based on comments made by the late Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira. Following the example of St. John Bosco who used to make similar talks for the boys of his College, each evening it was Prof. Plinio’s custom to make a short commentary on the lives of the next day’s saint in a meeting for youth in order to encourage them in the practice of virtue and love for the Catholic Church. TIA thought that its readers could profit from these valuable commentaries.

The texts of both the biographical data and the comments come from personal notes taken by Atila S. Guimarães from 1964 to 1995. Given the fact that the source is a personal notebook, it is possible that at times the biographic notes transcribed here will not rigorously follow the original text read by Prof. Plinio. The commentaries have also been adapted and translated for TIA’s site.

|

Saint of the Day | Home | Books | CDs | Search | Contact Us | Donate

© 2002- Tradition in Action, Inc. All Rights Reserved

|

|

|