The Saint of the Day

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

St. Simon of Crépy - September 30

Biographical selection:

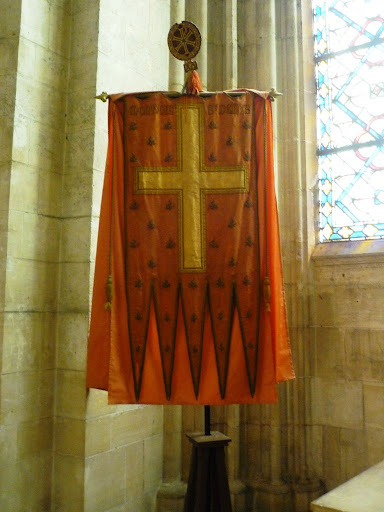

Simon was born in 1048, the son of the Count Raul of Vermandois, standard-bearer of the King of France. When the King declared a war, the Count of Vermandois, the military defender of the Abbey of St. Denis, would go there to kneel at the grave of the Patron Saint of France.

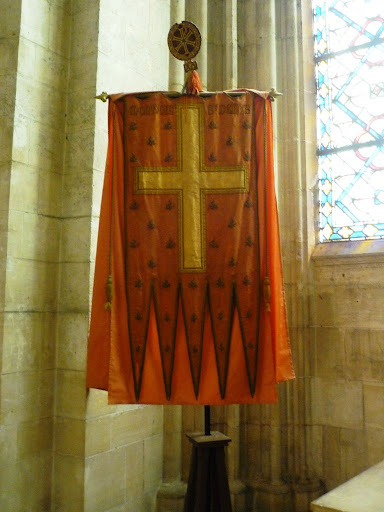

Then, according to a sacred ritual, he would receive the oriflamme, the King's battle standard. This high privilege passed from the family with St. Simon, who gave it along with his sizable domains to the Kings of France.

Simon was brought up in the court of William the Conqueror in Normandy, and at age 16 he was sent to the French Court to fulfill his function as standard-bearer.

Simon was brought up in the court of William the Conqueror in Normandy, and at age 16 he was sent to the French Court to fulfill his function as standard-bearer.

Simon was a close companion of the young King Phillip I, but this period was not good for him for he acquired an obsession for pleasure. One day, during a difficult hunt, he swore that thereafter he would love only evil and hate good.

At age 26 he entered into possession of the family domains and was obliged to wage a war against King Phillip I, who wanted to usurp his estates. Shaken by this action of the Sovereign, Simon was touched by grace and decided to change his life.

Taking advantage of a Truce of God, he went to Italy to visit the graves of the Holy Apostles and to ask Pope Gregory VII for a general absolution. He presented himself to the Pontiff in magnificent armor. From the Pope he heard these words: "Armor is not an attire of penance. If you want absolution, you must begin by stripping it off or the absolution will be worthless."

Then, after removing the symbols of his power and being scourged by the Pontiff and two religious men present at the audience, he received the papal pardon.

Afterwards, St. Gregory VII returned the armor to him, ordering him to go back to his domains to fight until he could achieve a durable peace.

Returning from Rome, Simon had to face another problem. Some nobles were trying to hasten his marriage to the daughter of the Count of Auvergne. But the young lady, who like Simon did not want to marry, escaped to the Convent of La Chaise Dieu.

Then, William, King of England, offered him the hand of his daughter, Adele. Simon, arguing his kinship to the young lady was too close, entered the Abbey of Saint Claude. His example influenced countless nobles of high rank to follow his example and become monks.

Then, William, King of England, offered him the hand of his daughter, Adele. Simon, arguing his kinship to the young lady was too close, entered the Abbey of Saint Claude. His example influenced countless nobles of high rank to follow his example and become monks.

There were so many feudal lords entering monasteries that St. Gregory VII became concerned. He wrote to St. Hugh, Abbot of Cluny, stating that all calamities come from the lack of good princes. But Divine Providence did not allow any places to be harmed because of those holy vocations.

As a religious, Simon acquired such an ascetic demeanor that he was able to convert the hardest heart. He rendered countless services to the Papacy, acting as the papal ambassador to Phillip I, who was oppressing the Church, as well as to William of England and his son Robert, who had taken up arms against his father; finally, he made negotiations with Robert Guiscard, Duke of Apulia. All of these missions were crowned with success.

He then wished to return to his hermitage, but St. Gregory VII advised him to go to the grave of St. Peter and ask for the Apostle to inspire him. Simon passed the night in prayer and at dawn he fell gravely ill. He asked the Pope to hear his confession – his last one. St. Gregory hastened to him and also administered the Last Rites and gave him the Viaticum. It was September 30, 1080. Simon was only 32-years-old.

Comments of Prof. Plinio:

This is a most beautiful selection that deserves some comments: First, regarding the general lines of the life of the Saint; second, regarding some of its details.

The general line is that he was a man of high lineage, one of those almost royal families that existed in the times of Feudalism. He was a childhood friend of the King of France and raised in the court of the future King of England. He was a young man known and linked by the royal blood of Europe who very early received an honorific office in France, where he had extensive lands in Vermandois.

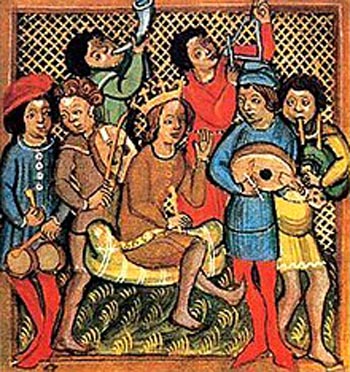

He received the honorific mission of being the standard bearer of the King of France when he would enter combat. It was a mission that required him to be in the Court of King Phillip I. But the Court of France was a place of pleasure, and when pleasures are splendid and alluring, they soften the soul: They give the soul a thirst for delights, drawing the soul away from the disposition to suffer. Immersed in this life of pleasure, so different from the austere life he had led in his province, Simon swerved from the good path and swore to love evil and hate good. That is, he practically consecrated himself to the Devil.

He received the honorific mission of being the standard bearer of the King of France when he would enter combat. It was a mission that required him to be in the Court of King Phillip I. But the Court of France was a place of pleasure, and when pleasures are splendid and alluring, they soften the soul: They give the soul a thirst for delights, drawing the soul away from the disposition to suffer. Immersed in this life of pleasure, so different from the austere life he had led in his province, Simon swerved from the good path and swore to love evil and hate good. That is, he practically consecrated himself to the Devil.

Then, a life of disappointments started: The King, who was the center of those pleasures, turned against him and wanted to confiscate his fief. The King initiated a harsh war against him, for, as King he was much more powerful than the Count. Simon had to bear that war and, as it progressed, he came to his senses.

In the Middle Ages the Church imposed some periods of peace in the wars between Catholics. These periods were called the Truce of God. So, a peace was imposed on various Holy Days, but also for long periods such as Lent, Advent and other times of the year. Simon took advantage of one of those long periods and went to visit the Pope. He went to do penance for the fact that he had, so to speak, delivered himself to the Devil. Since he was a feudal lord of high rank, he appeared before the Pope in magnificent armor, in part to honor the Sovereign Pontiff because the Kings and feudal lords would appear in their best apparel in the papal court.

St. Gregory VII was the personification of coherence, rectitude and strength. You remember the famous episode of him with Henry IV, Emperor of the Holy Roman German Empire. The latter had to remain three days in the snow outside of the Castle of Canossa dressed as a penitent and asking forgiveness of the Pope for the enormous sins he had committed. The Pope left him there and only opened the gates of the Castle to receive and pardon him because of strong pressure from those who were with him. Only for this reason did he receive Henry IV and reestablish him on the Imperial Throne.

Thus you can understand the words of St. Gregory to Simon of Crépy. He said: "Are you coming to make penance in this splendid armor? You must appear humbly in penitent garb; otherwise the absolution will be null." Why did he say this? Because humble external dress was a manifestation of repentance. No pardon is valid unless the man is repentant.

Thus you can understand the words of St. Gregory to Simon of Crépy. He said: "Are you coming to make penance in this splendid armor? You must appear humbly in penitent garb; otherwise the absolution will be null." Why did he say this? Because humble external dress was a manifestation of repentance. No pardon is valid unless the man is repentant.

Next, the Pope took a whip and chastised him. Again, it is perfectly logical: Had he not delivered himself to the Devil? Had he not renounced God? Therefore, it was good, noble and proper that this sinner should receive his penance from the hand of the Vicar of Christ to be restored to the state of grace. St. Gregory VII took the whip and inflicted a strong penance on him. It was not just a symbolic chastisement; in the Middle Ages the penances were for real. So, the Pope asked two strong monks to complete the job.

Here we see the seriousness of the Middle Ages, something so little known to men in our days. When a person would consecrate himself to Our Lady, that act was for life; when a person would consecrate himself to the Devil, it was also a serious act. It was not just a transient blasphemy to be lightly dismissed. The result is that, when it came time for the penance, he had to be truly beaten. So, the Pope did it.

Let us imagine a powerful man of our days – sadly, things have become so decadent that today's great men are in the industry. So, imagine a director of General Motors who goes to Rome to ask the Pope to give him a penance. How surprised he would have if Pius XII, let us say, were to take a whip and beat him as penance. The man would probably become indignant. He may even try to beat the Pope in return. Things have changed so much that today this scene with Pope Gregory VII and Simon of Crépy would be almost impossible to happen.

At that time, penance was taken seriously, and the Count returned to his lands a completely changed man.

Continued

The Saint of the Day features highlights from the lives of saints based on comments made by the late Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira. Following the example of St. John Bosco who used to make similar talks for the boys of his College, each evening it was Prof. Plinio’s custom to make a short commentary on the lives of the next day’s saint in a meeting for youth in order to encourage them in the practice of virtue and love for the Catholic Church. TIA thought that its readers could profit from these valuable commentaries.

The texts of both the biographical data and the comments come from personal notes taken by Atila S. Guimarães from 1964 to 1995. Given the fact that the source is a personal notebook, it is possible that at times the biographic notes transcribed here will not rigorously follow the original text read by Prof. Plinio. The commentaries have also been adapted and translated for TIA’s site.

Simon was born in 1048, the son of the Count Raul of Vermandois, standard-bearer of the King of France. When the King declared a war, the Count of Vermandois, the military defender of the Abbey of St. Denis, would go there to kneel at the grave of the Patron Saint of France.

Then, according to a sacred ritual, he would receive the oriflamme, the King's battle standard. This high privilege passed from the family with St. Simon, who gave it along with his sizable domains to the Kings of France.

The Count of Vermandois had the honor to be standard bearer of the Oriflamme

Simon was a close companion of the young King Phillip I, but this period was not good for him for he acquired an obsession for pleasure. One day, during a difficult hunt, he swore that thereafter he would love only evil and hate good.

At age 26 he entered into possession of the family domains and was obliged to wage a war against King Phillip I, who wanted to usurp his estates. Shaken by this action of the Sovereign, Simon was touched by grace and decided to change his life.

Taking advantage of a Truce of God, he went to Italy to visit the graves of the Holy Apostles and to ask Pope Gregory VII for a general absolution. He presented himself to the Pontiff in magnificent armor. From the Pope he heard these words: "Armor is not an attire of penance. If you want absolution, you must begin by stripping it off or the absolution will be worthless."

Then, after removing the symbols of his power and being scourged by the Pontiff and two religious men present at the audience, he received the papal pardon.

Afterwards, St. Gregory VII returned the armor to him, ordering him to go back to his domains to fight until he could achieve a durable peace.

Returning from Rome, Simon had to face another problem. Some nobles were trying to hasten his marriage to the daughter of the Count of Auvergne. But the young lady, who like Simon did not want to marry, escaped to the Convent of La Chaise Dieu.

A demeanor that could convert the hardet heart

There were so many feudal lords entering monasteries that St. Gregory VII became concerned. He wrote to St. Hugh, Abbot of Cluny, stating that all calamities come from the lack of good princes. But Divine Providence did not allow any places to be harmed because of those holy vocations.

As a religious, Simon acquired such an ascetic demeanor that he was able to convert the hardest heart. He rendered countless services to the Papacy, acting as the papal ambassador to Phillip I, who was oppressing the Church, as well as to William of England and his son Robert, who had taken up arms against his father; finally, he made negotiations with Robert Guiscard, Duke of Apulia. All of these missions were crowned with success.

He then wished to return to his hermitage, but St. Gregory VII advised him to go to the grave of St. Peter and ask for the Apostle to inspire him. Simon passed the night in prayer and at dawn he fell gravely ill. He asked the Pope to hear his confession – his last one. St. Gregory hastened to him and also administered the Last Rites and gave him the Viaticum. It was September 30, 1080. Simon was only 32-years-old.

Comments of Prof. Plinio:

This is a most beautiful selection that deserves some comments: First, regarding the general lines of the life of the Saint; second, regarding some of its details.

The general line is that he was a man of high lineage, one of those almost royal families that existed in the times of Feudalism. He was a childhood friend of the King of France and raised in the court of the future King of England. He was a young man known and linked by the royal blood of Europe who very early received an honorific office in France, where he had extensive lands in Vermandois.

The pleasures of court life diverted Simon

from the good path

Then, a life of disappointments started: The King, who was the center of those pleasures, turned against him and wanted to confiscate his fief. The King initiated a harsh war against him, for, as King he was much more powerful than the Count. Simon had to bear that war and, as it progressed, he came to his senses.

In the Middle Ages the Church imposed some periods of peace in the wars between Catholics. These periods were called the Truce of God. So, a peace was imposed on various Holy Days, but also for long periods such as Lent, Advent and other times of the year. Simon took advantage of one of those long periods and went to visit the Pope. He went to do penance for the fact that he had, so to speak, delivered himself to the Devil. Since he was a feudal lord of high rank, he appeared before the Pope in magnificent armor, in part to honor the Sovereign Pontiff because the Kings and feudal lords would appear in their best apparel in the papal court.

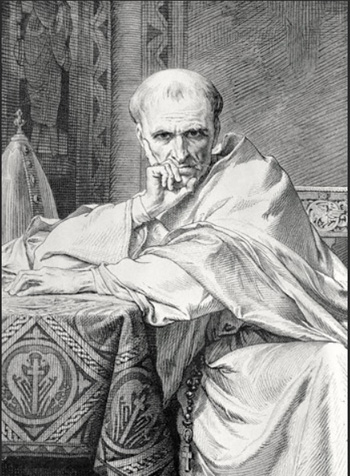

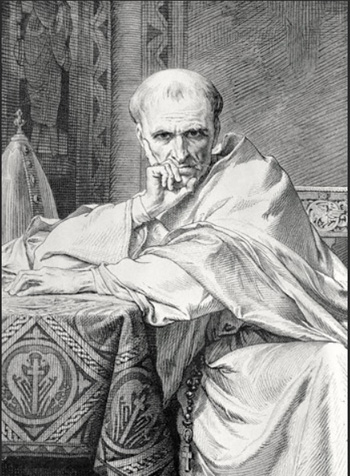

St. Gregory VII was the personification of coherence, rectitude and strength. You remember the famous episode of him with Henry IV, Emperor of the Holy Roman German Empire. The latter had to remain three days in the snow outside of the Castle of Canossa dressed as a penitent and asking forgiveness of the Pope for the enormous sins he had committed. The Pope left him there and only opened the gates of the Castle to receive and pardon him because of strong pressure from those who were with him. Only for this reason did he receive Henry IV and reestablish him on the Imperial Throne.

Pope St. Gregory VII: The personification of coherence, rectitude & strength

Next, the Pope took a whip and chastised him. Again, it is perfectly logical: Had he not delivered himself to the Devil? Had he not renounced God? Therefore, it was good, noble and proper that this sinner should receive his penance from the hand of the Vicar of Christ to be restored to the state of grace. St. Gregory VII took the whip and inflicted a strong penance on him. It was not just a symbolic chastisement; in the Middle Ages the penances were for real. So, the Pope asked two strong monks to complete the job.

Here we see the seriousness of the Middle Ages, something so little known to men in our days. When a person would consecrate himself to Our Lady, that act was for life; when a person would consecrate himself to the Devil, it was also a serious act. It was not just a transient blasphemy to be lightly dismissed. The result is that, when it came time for the penance, he had to be truly beaten. So, the Pope did it.

Let us imagine a powerful man of our days – sadly, things have become so decadent that today's great men are in the industry. So, imagine a director of General Motors who goes to Rome to ask the Pope to give him a penance. How surprised he would have if Pius XII, let us say, were to take a whip and beat him as penance. The man would probably become indignant. He may even try to beat the Pope in return. Things have changed so much that today this scene with Pope Gregory VII and Simon of Crépy would be almost impossible to happen.

At that time, penance was taken seriously, and the Count returned to his lands a completely changed man.

Continued

| |

|

|

The texts of both the biographical data and the comments come from personal notes taken by Atila S. Guimarães from 1964 to 1995. Given the fact that the source is a personal notebook, it is possible that at times the biographic notes transcribed here will not rigorously follow the original text read by Prof. Plinio. The commentaries have also been adapted and translated for TIA’s site.