|

Book Reviews

Catholic Dogmas Come from ‘Intense Feelings’

Margaret C. Galitzin

Summary of Orestes Brownson’s review of Essay on Development of Doctrine by John Henry Newman [Brownson’s Quarterly Review, July, 1846] - Full text here

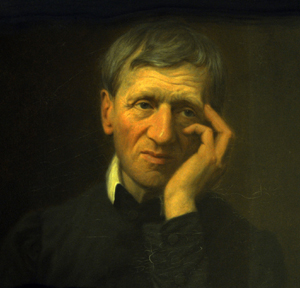

In 1846, Orestes Brownson wrote a stinging critique of John Henry Newman’s Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine. The famous American convert had been a Catholic for two years; his Anglican counterpart Newman had entered the Church one year earlier.

Orestes Brownson, a stauch defender of immutable doctrine and no salvation outside the Church |

The Essay, the last of Newman’s Oxford University works, was written in February 1843 in his effort to resolve what he viewed as changes made through history to Catholic doctrine. In it, he affirmed his conviction that in its dogmas Catholic doctrine does develop as the Holy Spirit assists the Church to grasp the truth implicit in the apostolic development. Using doctrines on papal supremacy, the cult of the Blessed Virgin, Purgatory and the invocation of saints, he claimed they had developed from the tradition of the early Church and were authentic continuations of the “process of dogmatization” at work in the early councils.

He left the Essay incomplete, stopping in the middle of a chapter, apparently having justified the step he had resolved to take. He and lifelong companion Ambrose St. John entered the Church and departed for Rome to study for the Catholic priesthood. It should be noted that in Rome Newman’s views in the Essay were received with sharp suspicion.

Even across the ocean in our more liberal America, Newman’s idea of an evolution of dogma was seen in many quarters as a threat to orthodoxy. The Bishops of New York, Louisville, Cincinnati and Pittsburg expressed their disagreements with that notion of development, upholding theologian Bossuet’s position that variation and change were in themselves characteristics of Protestantism and of error. It was, in fact, Bishop John Fitzpatrick of New York who encouraged Brownson to make his critique of Newman’s Essay, which earned him the gratitude of many American Prelates.

Developing Protestantism into Catholicity

Brownson began his critique noting that the proper thing for Newman to do with his Essay was to bury it. It was, he asserted, a great mistake to offer it to the public. Since now that Newman had converted and had eaten “the food of Angels,’” he should abandon his Protestant theory, which was both unnecessary and inadmissible. In Newman’s earnest effort “to develop Protestantism into Catholicity,” he had invented a theory that was “essentially anti-Catholic and Protestant.” (pp. 2-3)

Newman with his companion Ambrose St. John |

Newman’s major mistake, Brownson sustained, was that he did not distinguish between Christian dogma – which does not evolve – and Church theology and discipline, which do change. Newman’s premise, however, is that there is a perpetual growth, or continued increase and expansion of Christian doctrine, gains made from the investigations of faith and attacks of heresy.

This theory shakes the foundation of the Faith, Brownson asserted. Newman’s statement that the Church “went forth in haste, her dough unleavened, her creed incomplete, her understanding of the faith imperfect, ignorant” is false (p. 6).What the Church teaches is that Revelation was given complete, and there was no development or evolution of the original deposit.

How was the Church directed to make her additions and changes? Again, Newman tailored another strange theory saying the Church worked out dogmatic truth from implicit feelings. For example, on the doctrine of Purgatory, she “had a vague yet intense feeling of the truth,” which was later “digested into formal propositions or definite articles” (p. 8).

It is preposterous, Brownson accused, to base the deposit of the Faith on something as changeable as “intense feelings.” If this were the case, then today an article of faith can give rise to a new feeling, which later becomes opinion, and finally, in a later age yet, is imposed as dogmatic truth. Such a view, if followed out, “would suppress entirely the proper teaching authority of the Church, competent at any moment to declare infallible what is the precise truth revealed” (p. 8)

Christianity as ‘an idea’

Brownson futher objected to Newman’s view that Christianity came into the world as an “idea” rather than an institution. Christianity, Newman says, “came into the world as an idea rather than an institution, and has had to wrap itself in clothing, and fit itself with armor of its own providing, and form the instruments and methods of its own prosperity and warfare” (p. 9). According to Newman, Christianity was thrown upon the great concourse of men, to be developed and embodied by the action of their minds, stimulated and directed by the human mind.

Such view, Bronson countered, implied that the mind formed the dogmas, making them a product of human effort as the mind gradually developed a clearer understanding of the idea and created forms to concretize the idea. In such case, not only the dogmas she imposed but also the moral precepts she taught, the institutions she established and the rites she prescribed would all supposedly be products of the human mind. Thus, they ultimately can be governed, modified enlarged or contracted by it at its pleasure (pp. 9-10).

Not so! Brownson objected. Christianity was born from an original Revelation, full and complete in itself, and not merely an idea that needed to be realized or actualized by the human mind through the ages.

Heresies at the service of the Church

Brownson was highly offended at Newman’s attitude that heresies had provided an essential service to the Church by enabling her to develop and fully understand the sacred deposit of faith. “He sees no peculiar sin in them,” Brownson charged, but rather considers that they “anticipate the Church” and help her “to bring out and insist upon some particular aspect of the truth before her hour has come, before she has reached it in the regular course of development” (p. 13).

Newman never renounced the theories in his Essay |

He quoted Newman as praising Montanism as “a remarkable anticipation or presage of developments which soon began to show themselves in the Church.” Newman claimed that “the prophets of the Montanists prefigured the Church’s Doctors” and the heresiarch himself was the “anticipation of St. Francis.” The Novatian heresy anticipated the thinking of St. Benedict or St. Bruno (p. 13). In effect, Newman defended that orthodoxy is supposedly formed from the “raw material” supplied by the heretics.

Brownson sharply observed: “It is singular that it never occurred to Mr. Newman that possibly the heretical view which he seems to admire so much were simply corruptions of doctrines which the Church had taught before them, and that heresy is the corruption of orthodoxy, and not its raw material” (p. 14).

Brownson went on to critique Newman’s supposition that Revelation was first made exclusively through the written word, another Protestant notion he attempted to Catholicize. He also argued against the profoundly naturalistic vision of human and ecclesiastical history that characterize Newman’s Essay. Nor was Brownson impressed with Newman’s much-heralded seven criteria to prove the authenticity or falseness of developed doctrine. He ran through the lot, subjecting them to his own tests, finding them faulty and deficient (pp. 4-5).

Theories accepted as facts

Brownson’s critique of the Essay has received little attention from the Catholic public, especially in conservative and traditionalist circles usually so zealous in guarding orthodoxy. This is unfortunate, in my view, for several reasons.

First, Brownson criticism is masterly written and his logic irreproachable, clearly shows Newman’s positions that deviate from orthodox Catholicism. Anyone who reads his review – and it is well worth the effort – will also appreciate the politeness of Brownson, who repeatedly asserted that his criticism was based on Newman’s thesis, and not his person. Further, Brownson invited Newman to correct him should he be mistaken in his evaluation.

Benedict promotes Newman as a precursor of Progressivism |

But Newman never responded to the challenge. He viewed this criticism as a personal attack, making surly comments to friends about the “half-converted Yankee” and “auto-didaktoi (self-appointed) lay theologian.” (1) The latter criticism is inconsistent since he always supported the liberal position of increasing the role of the lay theologian in the Church. But Newman also had a well-documented tendency to hold bitter grudges against anyone who criticized his works.

Second, Brownson foresaw the future danger should Newman’s theory become accepted in the Church. Unless his theory was renounced, Brownson affirmed, it would either ultimately lead Newman himself out of communion with the Church or, much worse, be wrongly absorbed into the Catholic Church (p. 1).

In fact, the latter happened. His “pioneer” work established the idea of the development of dogma as a principle later held by the Modernists. Taken up by the Progressivists, it was consecrated at Vatican II, invoked in both the Declaration of Religion Freedom and the Constitution on Revelation. (2)

Newman alleged he was simply showing that the Catholic Church of his time was in continuity with that of the Apostles and the Fathers. But Vatican II did what Brownson feared could happen – it used this ‘theory’ to justify new advances and actual shifts in doctrine, such as its teaching on religious freedom. Jesuit Avery Dulles singled out Newman as anticipating the thought of Karl Rahner “to the effect that every dogmatic proclamation is not only an end, but also a beginning.” (3)

Someone could object that this work was written when Newman was a Protestant, and, therefore, should be disregarded as irrelevant after Newman’s conversion to Catholicism. The objection would be pertinent if he had rejected its theories or buried it, as Brownson suggested. On the contrary, he offered the work to the public and continued to defend its thesis until the end of his life. Thus, the objection is invalid.

Most American Catholics have not read Newman’s suspect theological works, such as the Essay on Development of Doctrine. His fame and popularity rest on his letters and sermons on piety and religious devotion. Let those well-meaning Catholic take the time to read at least Brownson’s criticism of Newman’s Essay, and they may begin to question the orthodoxy of the “oracle from Littlemore.” They may also begin to wonder if the beatification of Newman, rightly called the Father of Vatican II by the progressivists themselves, has the underlying purpose of giving needed impetus to the Council at a time when dissatisfaction with it is significantly increasing.

1. Patrick Carey, Orestes A. Brownson: American Religious Weathervane, Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Pub. Co., 2004, p. 176

2. Avery Dulles, John Henry Newman, London: Continuum, 2002, p. 154

3. Ibid., p. 102.

Posted September 13, 2010

Related Topics of Interest

Newman's Longings for Vatican II Newman's Longings for Vatican II

Rome to Newman: You Are the Head of the English Liberal Catholics Rome to Newman: You Are the Head of the English Liberal Catholics

Another Look at John Henry Cardinal Newman Another Look at John Henry Cardinal Newman

Newman's Admiration for Anglicanism Never Ceased Newman's Admiration for Anglicanism Never Ceased

Newman Is the Most Dangerous Man In England Newman Is the Most Dangerous Man In England

Drawing Rabbits from the Hat in England Drawing Rabbits from the Hat in England

A 'Gay' Newman? A 'Gay' Newman?

The Liberal Newman Americans Don’t Know The Liberal Newman Americans Don’t Know

Card. Newman Recognized as a Homosexual Card. Newman Recognized as a Homosexual

Related Works of Interest

|

|

Book Reviews | Home | Books | CDs | Search | Contact Us | Donate

© 2002-

Tradition in Action, Inc. All Rights Reserved

|

|

|