Movie Review

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

How Hollywood Prepared for the ‘60s

The great strides of the Revolution of the ‘60s need no introduction. They ended in the thunderous upheaval of the Hippie Revolution. Contrary to what public opinion believes in general, the ‘60s were not the antithesis of the ’50s. The ‘50s were, albeit subtle, a cultural preparation that set the stage for the ‘60s Revolution, a decade that helped to intensify and unleash its power.

In his penetrating analysis, Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira explains the Revolution has two paces: “One is fast and is generally destined to fail in the short term. The other has usually been crowned with success and is much slower." (1)

In his penetrating analysis, Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira explains the Revolution has two paces: “One is fast and is generally destined to fail in the short term. The other has usually been crowned with success and is much slower." (1)

A little-known book about movies by Peter Biskind, Seeing Is Believing: How Hollywood Taught Us to Stop Worrying and Love the Fifties, offers a wealth of information about how Hollywood was supporting the revolutionary process at a slow pace.

In general, the book questions the story of the ‘50s as being a happy, harmonic decade, different from the divided and radicalized society of the ‘60s. The movies played a role in this fiction, helping to make “a particular set of values seem universal.” It was the Hollywood world with the good life and the good ending that Americans were eager to feast on because they proved that the American ‘system’ was good, the best in the world, so that is what Hollywood produced. (2)

Even the ”dissident” movies that criticized the left and the right, parrying by the left and the right against the center, i.e. the military, the government, big corporations and the like, seemed to be in some kind of dialogue with it. These "decoded” or “encoded" messages are what the books aims to divulge.

In the ‘50s Communism never had any “purchase power” on movie screens because American public was generally anti-communist. So, every movie that was produced (in the ’50s), no matter how trivial or escapist, Biskind tells us, was made in the shadow of the anti-communist witch-hunt, subject to the strictures of the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC). (3) So, most films generally reflected that anti-communism and stressed the virtues of conformity and domesticity.

But Hollywood found ways to circumvent these structures by stealth, and create a climate for revolt. The most popular movies that made the greatest impact, the ones with the biggest budgets - movies like Giant, The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit and Rebel Without a Cause - sent their anti-establishment message subtly.

This is the value of Biskind’s analysis: he demonstrates the Revolution working effectively in Hollywood at slow pace.

The Wild One and High Noon

In the movie The Wild One (1954) for example, starring Marlon Brando as the leader of a pack of motorcycle outlaws, the defiance of the middle class and the political center is evident. It is this defiance that would crystallize a decade later in the anti-war movement as well as in the atmosphere of Vatican II.

One immediate consequence of The Wild One among teenage boys was a new hip look that emerged. The “cool” boys took to wearing black leather jackets and motorcycle boots; a song by that title, written by Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, was on the top-10 songs list in less than a year. If there is one word that incarnates the spirit of the ’60s, it is the word defiance, which was being promoted in this film in the ‘50s.

One immediate consequence of The Wild One among teenage boys was a new hip look that emerged. The “cool” boys took to wearing black leather jackets and motorcycle boots; a song by that title, written by Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, was on the top-10 songs list in less than a year. If there is one word that incarnates the spirit of the ’60s, it is the word defiance, which was being promoted in this film in the ‘50s.

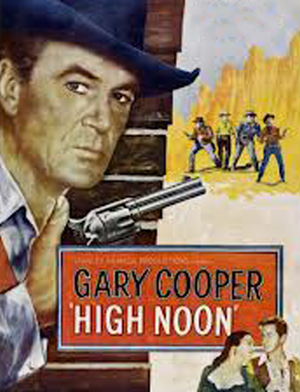

An even better example to illustrate the subliminal tactics of conditioning an audience to revolution is the movie High Noon (1952).

For those who have viewed High Noon, it is a good bet that the vast majority will categorize it as a right-wing film, which, indeed, it appears to be. On the contrary, it was leftist through and through.

As Biskind notes in his chapter on that film, "The film was made by leftists on the receiving end of the blacklist, who felt betrayed and embattled for the same reasons conservatives felt secure and comfortable.” (4)

The story takes place in a town called Hadleyville in the 19th century, where Will Kane (Gary Cooper) is the Marshal. Kane had just married Amy (Grace Kelly) and was retiring from law enforcement. The new Marshall won't arrive until the next day, but Kane’s circle of friends joke that they can handle things for one day.

Then, we find out that a man Kane had arrested and convicted for murder five years earlier, Frank Miller, has just been paroled. He and “three gunnies” have vowed to kill Kane and are on their way to town.

Amy, a Quaker, against killing in principle, threatens to leave Kane unless he leaves town and avoids a fight. Kane explains to her that he must stay, because in the first place they will catch up with him as he flees through the prairie and, that aside, he must stay and do his duty.

Kane is sure he can enlist some help and recruit some deputies. But his permanent deputy quits, so Kane goes scouting for others. First he tries the bar, but the drunkards laugh him down. Then he goes to the church, which is in the middle of its services. Here we come to the encoded anti-centrist gist of the story.

Those at the church are the good citizens of the town, the successful businessmen and property owners. They represent the centrists of the town. These good citizens vote and ultimately decide that Kane should leave because a wild-west shoot out would be bad for business. Money comes first. Also a black cloud falls upon the politicians who paroled Miller, another censure of the U.S. government, a centrist entity. Kane is left to fight the four killers alone.

Those at the church are the good citizens of the town, the successful businessmen and property owners. They represent the centrists of the town. These good citizens vote and ultimately decide that Kane should leave because a wild-west shoot out would be bad for business. Money comes first. Also a black cloud falls upon the politicians who paroled Miller, another censure of the U.S. government, a centrist entity. Kane is left to fight the four killers alone.

So, how is this scenario of good-guy vs. bad guy changed into a politically charged leftist propaganda piece? Biskind gives the answer: "We know this is a left-wing film because it was made by leftists like producer Stanley Kramer and scriptwriter Carl Foreman [both members of the Communist Party, the latter later blacklisted] who later said it was. Once the Millers [the bad guys] were equated with HUAC or McCarthy, then the craven townies became ‘friendly witnesses,’ as those who had cooperated with the witch-hunt were called.” (5) Thus, the film’s purpose was accomplished.

What High Noon was about at that time, said Foreman afterward, was Hollywood, and no other place but Hollywood, and its aim was to create sympathy for the blacklisted communists…

The message Kramer and Foreman were sending in High Noon was this: The capitalists are rotten, hypocritical money-lovers whose souls have nothing of honor. Other movies he analyzes with underlying messages of challenging authority are 12 Angry Men, Panic in the Streets and My Darling Clementine.

The valuable lesson for counter-revolutionaries here is that, already in the “good ole ‘50s,” the revolutionary forces in Hollywood were subtly undermining society and giving honor and political clout to rebels. It is good for counter-revolutionaries to analyze movies under this light.

Of course, that legacy of defiance gave its full fruits in the ‘60s in both temporal and spiritual society. Today, it has reached the highest places in the Church and the world, with a Pope who preaches that the recitation of prayers is falling into ideology, and a president who flaunts the Constitution while denigrating everything Americans hold dear.

May Our Lady of Prompt Succor pray for all in the Catholic resistance and those who still honor our country's heritage.

Many of the ‘50s movies had subversive anti-establishment messages

A little-known book about movies by Peter Biskind, Seeing Is Believing: How Hollywood Taught Us to Stop Worrying and Love the Fifties, offers a wealth of information about how Hollywood was supporting the revolutionary process at a slow pace.

In general, the book questions the story of the ‘50s as being a happy, harmonic decade, different from the divided and radicalized society of the ‘60s. The movies played a role in this fiction, helping to make “a particular set of values seem universal.” It was the Hollywood world with the good life and the good ending that Americans were eager to feast on because they proved that the American ‘system’ was good, the best in the world, so that is what Hollywood produced. (2)

Even the ”dissident” movies that criticized the left and the right, parrying by the left and the right against the center, i.e. the military, the government, big corporations and the like, seemed to be in some kind of dialogue with it. These "decoded” or “encoded" messages are what the books aims to divulge.

In the ‘50s Communism never had any “purchase power” on movie screens because American public was generally anti-communist. So, every movie that was produced (in the ’50s), no matter how trivial or escapist, Biskind tells us, was made in the shadow of the anti-communist witch-hunt, subject to the strictures of the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC). (3) So, most films generally reflected that anti-communism and stressed the virtues of conformity and domesticity.

But Hollywood found ways to circumvent these structures by stealth, and create a climate for revolt. The most popular movies that made the greatest impact, the ones with the biggest budgets - movies like Giant, The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit and Rebel Without a Cause - sent their anti-establishment message subtly.

This is the value of Biskind’s analysis: he demonstrates the Revolution working effectively in Hollywood at slow pace.

The Wild One and High Noon

In the movie The Wild One (1954) for example, starring Marlon Brando as the leader of a pack of motorcycle outlaws, the defiance of the middle class and the political center is evident. It is this defiance that would crystallize a decade later in the anti-war movement as well as in the atmosphere of Vatican II.

In The Wild One Marlon Brando introduces the model of rebellion for the youth

An even better example to illustrate the subliminal tactics of conditioning an audience to revolution is the movie High Noon (1952).

For those who have viewed High Noon, it is a good bet that the vast majority will categorize it as a right-wing film, which, indeed, it appears to be. On the contrary, it was leftist through and through.

As Biskind notes in his chapter on that film, "The film was made by leftists on the receiving end of the blacklist, who felt betrayed and embattled for the same reasons conservatives felt secure and comfortable.” (4)

The story takes place in a town called Hadleyville in the 19th century, where Will Kane (Gary Cooper) is the Marshal. Kane had just married Amy (Grace Kelly) and was retiring from law enforcement. The new Marshall won't arrive until the next day, but Kane’s circle of friends joke that they can handle things for one day.

Then, we find out that a man Kane had arrested and convicted for murder five years earlier, Frank Miller, has just been paroled. He and “three gunnies” have vowed to kill Kane and are on their way to town.

Amy, a Quaker, against killing in principle, threatens to leave Kane unless he leaves town and avoids a fight. Kane explains to her that he must stay, because in the first place they will catch up with him as he flees through the prairie and, that aside, he must stay and do his duty.

Kane is sure he can enlist some help and recruit some deputies. But his permanent deputy quits, so Kane goes scouting for others. First he tries the bar, but the drunkards laugh him down. Then he goes to the church, which is in the middle of its services. Here we come to the encoded anti-centrist gist of the story.

The message - capitalists and the government are corrupt

So, how is this scenario of good-guy vs. bad guy changed into a politically charged leftist propaganda piece? Biskind gives the answer: "We know this is a left-wing film because it was made by leftists like producer Stanley Kramer and scriptwriter Carl Foreman [both members of the Communist Party, the latter later blacklisted] who later said it was. Once the Millers [the bad guys] were equated with HUAC or McCarthy, then the craven townies became ‘friendly witnesses,’ as those who had cooperated with the witch-hunt were called.” (5) Thus, the film’s purpose was accomplished.

What High Noon was about at that time, said Foreman afterward, was Hollywood, and no other place but Hollywood, and its aim was to create sympathy for the blacklisted communists…

The message Kramer and Foreman were sending in High Noon was this: The capitalists are rotten, hypocritical money-lovers whose souls have nothing of honor. Other movies he analyzes with underlying messages of challenging authority are 12 Angry Men, Panic in the Streets and My Darling Clementine.

The valuable lesson for counter-revolutionaries here is that, already in the “good ole ‘50s,” the revolutionary forces in Hollywood were subtly undermining society and giving honor and political clout to rebels. It is good for counter-revolutionaries to analyze movies under this light.

Of course, that legacy of defiance gave its full fruits in the ‘60s in both temporal and spiritual society. Today, it has reached the highest places in the Church and the world, with a Pope who preaches that the recitation of prayers is falling into ideology, and a president who flaunts the Constitution while denigrating everything Americans hold dear.

May Our Lady of Prompt Succor pray for all in the Catholic resistance and those who still honor our country's heritage.

- Plinio Correa de Oliveira, Revolution and Counter-Revolution, The Foundation for a Christian civilization, p. 47

- Peter Biskind, Seeing is Believing – How Hollywood Taught us to Stop Worrying and Love the Fifties, NY: Pantheon Bks, 1983, passim.

- Ibid., p. 4

- Ibid., p. 47

- Ibid., p. 48

Posted December 18, 2013

______________________

______________________