Movies & Shows

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Movie & Book Comparison - Part II

Egalitarianism, Tolerance & Independence

in Little Women

novel by Louisa May Alcott, NY: Scholastic Inc, 2000

Elizabeth A. Lozowski

Continuing my review of Little Women, I will now analyze two of the most important side characters, Laurie and Marmee, who both contribute to very dangerous aspects of the story.

The boy next door encourages egalitarianism

In the book, Laurie, the next-door neighbor, is a good-spirited lad, well-bred and entertaining, but also lazy, moody and fond of pranks. His manners, usually excellent, take the American casual turn when he is with Jo, teasing and larking with her as if she were one of the boys.

Although he enjoys elegant society, he is also quite comfortable in informal settings. In fact, his favorite place to be is in the March home, where he is constantly joking and horsing with the March sisters. In this way, Alcott is trying to idealize the American casual and egalitarian home, without gravitas or formality.

Although he enjoys elegant society, he is also quite comfortable in informal settings. In fact, his favorite place to be is in the March home, where he is constantly joking and horsing with the March sisters. In this way, Alcott is trying to idealize the American casual and egalitarian home, without gravitas or formality.

Laurie represents the lazy American man who does not like to work or study, whose ambition is to enjoy life: to play, travel and flirt with ladies. This tendency towards sloth causes him to be slightly effeminate as he is willing to let the women take charge in order to avoid the trouble of doing so himself.

It is only after a woman tells him what to do that Laurie begins to work hard. It is Jo who compels him to improve, lecturing and scolding him until he finally graduates from college with honors. Later, in Europe, Amy replaces Jo in that role, admonishing him to make something of himself. Laurie’s only motivation – and even solace – is a woman’s guiding hand in both the book and the movie.

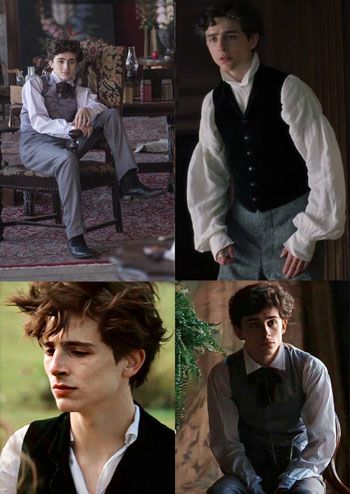

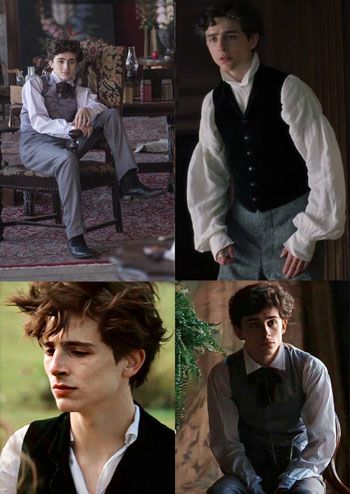

As would be expected, Gerwig chooses Timothée Chalamet, a thoroughly effeminate modern man, to play Laurie. Chalamet’s Laurie is a moon-eyed romantic who gazes at the girls with a dumb look, entirely devoted to swooning over them. There is not a spark of manliness in him. Although Laurie had a manly spirit in the book, his tendencies toward laziness and romanticism find their fruition in the 2019 movie, and I am sure that Alcott would have been pleased with this new pet for her little women.

Marmee preaches tolerance & independence

In the important character of Marmee, the book and movie coincide. Although each portrays her somewhat differently to suit the audience of the times, Marmee is consistent in her passion for independence and tolerance. Trusting in the innate goodness of man, she lets the girls do as they wish and learn for themselves what is right and wrong.

Marmee is never a strong presence in the girls’ everyday lives, staying either in “Marmee’s corner” where she quietly reads and does womanly crafts, or going outside of the home to perform charitable acts for others. To illustrate more clearly Marmee’s feminist stance towards women, the following quote from the movie, although not in the book, captures her spirit: “Girls have to go out into the world and make up their own minds about things.”

Marmee, as Alcott's own mother did, teaches her “little women” to consult their own consciences in making moral decisions and to be independent of society's institutions, including organized religion. Man is only truly himself when he thinks and acts independently, relying on his own natural goodness to guide his path in life. This is her creed, and all her little "sermons" and "words of wisdom" preach the values of the Transcendentalism in which the Alcott family was deeply immersed.

Marmee, as Alcott's own mother did, teaches her “little women” to consult their own consciences in making moral decisions and to be independent of society's institutions, including organized religion. Man is only truly himself when he thinks and acts independently, relying on his own natural goodness to guide his path in life. This is her creed, and all her little "sermons" and "words of wisdom" preach the values of the Transcendentalism in which the Alcott family was deeply immersed.

Indeed, in the book, there is not one mention of the March family going to church or saying formal prayers of any sort. There is only one interesting incident involving religion in which Amy meets a French Catholic maid when staying at Aunt March’s house. The pious maid makes a little chapel with a picture of the Madonna and Christ Child for Amy, telling her to take some time out of the day to pray before it, which Amy does and becomes better for it. (As would be expected, this incident is absent from the new film.)

Although Amy never becomes Catholic, she loves the picture of Mary and takes home a copy, which she dutifully shows to Marmee. Contrary to what might be expected from someone nominally Protestant, Marmee does not reject the picture but only smiles and says, “It is an excellent plan to have some place where we can go to be quiet, when things vex or grieve us. There are a good many hard times in this life of ours, but we can always bear them if we ask help in the right way” (Little Women, chap. 20, p. 230).

Thus, the tolerant Marmee presents the perfect 21st century ecumenical mother: self-reliant, liberal and tolerant, encouraging good not for the love of God but for the love of humanity. To her, the old ways of educating and forming children that followed set laws and enforced decorum and civility are empty formulas. What is important for Marmee is to be sincere and true to oneself.

That is what the hippy revolution of the 1960s preached. In a strange and unexpected way, Little Women prepared girls to embrace that Revolution, with its feminist call for equality and demand to do away with all conventions and restraints.

The dangers of book & movie

What are the main dangers of both the book and the movie? Let me name just a few reasons why I would not encourage Catholic parents to let their daughters enter the world of Little Women:

1) The March girls have too close a familiarity with men; conventions, modesty and discretion are set aside as superfluous as the girls go off without chaperones to dances, theaters and outings with youth. Their friendship with Laurie, in particular, is too familiar, leaving out the notion of original sin and leading to modern dating. In Catholic society, young women and men are instructed to avoid familiarity with the other sex. Stories like these confuse this good custom.

1) The March girls have too close a familiarity with men; conventions, modesty and discretion are set aside as superfluous as the girls go off without chaperones to dances, theaters and outings with youth. Their friendship with Laurie, in particular, is too familiar, leaving out the notion of original sin and leading to modern dating. In Catholic society, young women and men are instructed to avoid familiarity with the other sex. Stories like these confuse this good custom.

Yet, as can be seen in Little Women, it is impossible for young men and young women to simply “be friends” and work together familiarly. No matter how much the girls deny it, a romantic relationship begins to bud – either in fact or in the imagination as with Laurie and Jo.

2) All the characters present a false notion of virtue. What they pursue is a naturalist “virtue” – being true to one's conscience (not the Law of God), doing good for humanity (not for the greater glory of God and Our Lady), etc. It is the world order promoted by the United Nations, not the Reign of Christ on earth, for which the Marsh family strives.

No real supernatural presence exists, and, so, no one is really good, not even Beth. Above all, none of the characters are idealistic: they simply strive to work hard and be “useful” in society. They are not good role models for girls or boys.

3) The seeds of feminism are planted and fertilized in works like this. How many Catholic girls have sympathized with the lively nonconformist Jo who wants “more than home and family,” who cries for equality with men in the home and work place? And even without a sympathy for Jo, the glorification of independence, held up as a virtue throughout the story, is a deadly poison to true femininity.

Little Women is not a story for Catholic homes. The book is all the more dangerous in that it has an attraction for young girls. When reading the book, I actually found myself enjoying it, despite all of the revolutionary tendencies, because it is well written and has some memorable scenes. The depiction of home life and sisterly love has a charm that can catch Catholics unawares. However, the 2019 film, that lacked this charm, exposes the true nature of the story.

I will conclude with a brief description of the ending of the movie, which is, I hope, sufficient to convince Catholics that it is not worth watching.

I will conclude with a brief description of the ending of the movie, which is, I hope, sufficient to convince Catholics that it is not worth watching.

Whereas in her book Alcott had to resign herself to making Jo conform, at least in practice, to the “constraints” placed on women, Gerwig completely liberates Jo to act like a man. Jo’s feminist longings are fulfilled in the modern Jo who does whatever she likes: publishes a book, runs a school, teaches boys and girls to be equal. She even marries a man to keep her from being lonely, and it is she who catches him, chasing after him with her sisters when he is on his way to the train station to leave.

By the end of the movie, the women are all in charge, contentedly giving the orders in the little families they “chose” to have. While their husbands hold the babies, the “Little Women” gather together making the decisions about how Jo’s co-ed school – a modern, egalitarian utopia – should be run. The boys and girls play, study, fence and cavort together, unfettered and disordered.

It is a fairytale ending for the little feminist women and one of which, I am certain, Louisa May Alcott would highly approve.

The boy next door encourages egalitarianism

In the book, Laurie, the next-door neighbor, is a good-spirited lad, well-bred and entertaining, but also lazy, moody and fond of pranks. His manners, usually excellent, take the American casual turn when he is with Jo, teasing and larking with her as if she were one of the boys.

A moon-eyed effeminate Laurie

Laurie represents the lazy American man who does not like to work or study, whose ambition is to enjoy life: to play, travel and flirt with ladies. This tendency towards sloth causes him to be slightly effeminate as he is willing to let the women take charge in order to avoid the trouble of doing so himself.

It is only after a woman tells him what to do that Laurie begins to work hard. It is Jo who compels him to improve, lecturing and scolding him until he finally graduates from college with honors. Later, in Europe, Amy replaces Jo in that role, admonishing him to make something of himself. Laurie’s only motivation – and even solace – is a woman’s guiding hand in both the book and the movie.

As would be expected, Gerwig chooses Timothée Chalamet, a thoroughly effeminate modern man, to play Laurie. Chalamet’s Laurie is a moon-eyed romantic who gazes at the girls with a dumb look, entirely devoted to swooning over them. There is not a spark of manliness in him. Although Laurie had a manly spirit in the book, his tendencies toward laziness and romanticism find their fruition in the 2019 movie, and I am sure that Alcott would have been pleased with this new pet for her little women.

Marmee preaches tolerance & independence

In the important character of Marmee, the book and movie coincide. Although each portrays her somewhat differently to suit the audience of the times, Marmee is consistent in her passion for independence and tolerance. Trusting in the innate goodness of man, she lets the girls do as they wish and learn for themselves what is right and wrong.

Marmee is never a strong presence in the girls’ everyday lives, staying either in “Marmee’s corner” where she quietly reads and does womanly crafts, or going outside of the home to perform charitable acts for others. To illustrate more clearly Marmee’s feminist stance towards women, the following quote from the movie, although not in the book, captures her spirit: “Girls have to go out into the world and make up their own minds about things.”

Marmee, encouraging Jo's independence & feminism; never present on boy/girl outings

Indeed, in the book, there is not one mention of the March family going to church or saying formal prayers of any sort. There is only one interesting incident involving religion in which Amy meets a French Catholic maid when staying at Aunt March’s house. The pious maid makes a little chapel with a picture of the Madonna and Christ Child for Amy, telling her to take some time out of the day to pray before it, which Amy does and becomes better for it. (As would be expected, this incident is absent from the new film.)

Although Amy never becomes Catholic, she loves the picture of Mary and takes home a copy, which she dutifully shows to Marmee. Contrary to what might be expected from someone nominally Protestant, Marmee does not reject the picture but only smiles and says, “It is an excellent plan to have some place where we can go to be quiet, when things vex or grieve us. There are a good many hard times in this life of ours, but we can always bear them if we ask help in the right way” (Little Women, chap. 20, p. 230).

Thus, the tolerant Marmee presents the perfect 21st century ecumenical mother: self-reliant, liberal and tolerant, encouraging good not for the love of God but for the love of humanity. To her, the old ways of educating and forming children that followed set laws and enforced decorum and civility are empty formulas. What is important for Marmee is to be sincere and true to oneself.

That is what the hippy revolution of the 1960s preached. In a strange and unexpected way, Little Women prepared girls to embrace that Revolution, with its feminist call for equality and demand to do away with all conventions and restraints.

The dangers of book & movie

What are the main dangers of both the book and the movie? Let me name just a few reasons why I would not encourage Catholic parents to let their daughters enter the world of Little Women:

An easy familiarity that leads to romance

Yet, as can be seen in Little Women, it is impossible for young men and young women to simply “be friends” and work together familiarly. No matter how much the girls deny it, a romantic relationship begins to bud – either in fact or in the imagination as with Laurie and Jo.

2) All the characters present a false notion of virtue. What they pursue is a naturalist “virtue” – being true to one's conscience (not the Law of God), doing good for humanity (not for the greater glory of God and Our Lady), etc. It is the world order promoted by the United Nations, not the Reign of Christ on earth, for which the Marsh family strives.

No real supernatural presence exists, and, so, no one is really good, not even Beth. Above all, none of the characters are idealistic: they simply strive to work hard and be “useful” in society. They are not good role models for girls or boys.

3) The seeds of feminism are planted and fertilized in works like this. How many Catholic girls have sympathized with the lively nonconformist Jo who wants “more than home and family,” who cries for equality with men in the home and work place? And even without a sympathy for Jo, the glorification of independence, held up as a virtue throughout the story, is a deadly poison to true femininity.

Little Women is not a story for Catholic homes. The book is all the more dangerous in that it has an attraction for young girls. When reading the book, I actually found myself enjoying it, despite all of the revolutionary tendencies, because it is well written and has some memorable scenes. The depiction of home life and sisterly love has a charm that can catch Catholics unawares. However, the 2019 film, that lacked this charm, exposes the true nature of the story.

The women in the forefront, the men behind; below, a scene from the egalitarian utopian school

Whereas in her book Alcott had to resign herself to making Jo conform, at least in practice, to the “constraints” placed on women, Gerwig completely liberates Jo to act like a man. Jo’s feminist longings are fulfilled in the modern Jo who does whatever she likes: publishes a book, runs a school, teaches boys and girls to be equal. She even marries a man to keep her from being lonely, and it is she who catches him, chasing after him with her sisters when he is on his way to the train station to leave.

By the end of the movie, the women are all in charge, contentedly giving the orders in the little families they “chose” to have. While their husbands hold the babies, the “Little Women” gather together making the decisions about how Jo’s co-ed school – a modern, egalitarian utopia – should be run. The boys and girls play, study, fence and cavort together, unfettered and disordered.

It is a fairytale ending for the little feminist women and one of which, I am certain, Louisa May Alcott would highly approve.

Charming depictions of sisterly affection

make the book all the more dangerous

Posted July 10, 2020

______________________

______________________