Lent & Holy Week

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Penitential Psalms - VI

De Profundis: The Prayer of the Afflicted Soul

Let us turn now to one of the most famous psalms De Profundis.

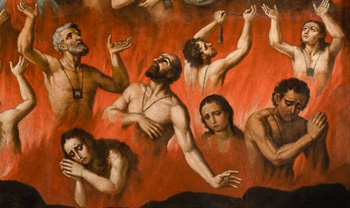

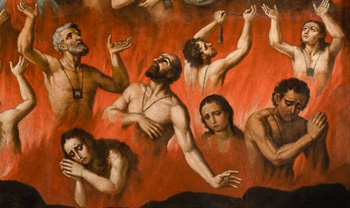

It is interesting that the De Profundis is applied to the Souls of Purgatory by the Church because the Poor Souls there are also in the situation of great affliction. It is much the same to sing the Requiem or the De Profundis, very appropriate and very beautiful.

It is interesting that the De Profundis is applied to the Souls of Purgatory by the Church because the Poor Souls there are also in the situation of great affliction. It is much the same to sing the Requiem or the De Profundis, very appropriate and very beautiful.

It is a prayer for the afflicted on this earth, the afflicted innocent man as well as the afflicted guilty man on this earth, but also for the guilty afflicted souls in the other world, who are the Souls in Purgatory.

All of the Penitential Psalms can be applied to the Souls in Purgatory, but the psalm De Profundis has something special for this purpose.

'Out of the depths have I cried to Thee, O Lord'

The text begins: “Out of the depths I have cried to Thee, O Lord, Lord, hear my voice. Let Thy ears be attentive to the voice of my supplication.”

These two verses make a single whole. The De Profundis well translated is plural and properly means “from the depths,” that is, from various depths. That is to say, from the greatest depths of the depths, from the blackest of afflictions, from the depths of the worst of sins, I have cried to You, O Lord.

It happens that God is in the highest of the Heavens, at the extreme opposite end of the deepest of the depths. Thus is He the Holy One in relation to the sinner, for He is the extreme opposite.

It happens that God is in the highest of the Heavens, at the extreme opposite end of the deepest of the depths. Thus is He the Holy One in relation to the sinner, for He is the extreme opposite.

From this realization comes a fear. Will He hear my voice? Then the plea, “Lord, hear my voice.”

This is the first request, which begins the holy circle of pleas and acts of confidence in His mercy. Since I know that my voice cannot be heard because I am so miserable, I begin by first asking that my voice be heard.

This is an act of confidence. I can at least ask to be heard, which is just a tiny bit of mercy that is always within the reach of everyone, even the most miserable, even the most afflicted in unimaginable lost conditions, even the most condemned soul in Purgatory. From these depths one can ask for something: “Lord, hear my voice.”

'Let thy ears be attentive to the voice of my supplication'

Then, he insists on the request: "Let Thy ears be attentive to the voice of my supplication."

Here we have notion of a distracted God who does not want to pay attention, who pretends not to hear, and of a believer, a poor man who knows that God is pretending He does not hear or seems not to hear. But in fact He does. If we insist with Him, He ends up listening. If we humbly ask and ask again and again, He will answer us.

At the crux of his idea of a prodigious separation between God and the sinner – which really does exist – there is also the idea of an infrangible mercy. There is an ear that at least hears when people beg: “Please listen."

This play of light and shadows, expressed here in a touching way, is very beautiful, showing the sinner who knows the malice of his sin and humbly recognizes it. And he presents himself before God by confessing the sin he has committed.

This play of light and shadows, expressed here in a touching way, is very beautiful, showing the sinner who knows the malice of his sin and humbly recognizes it. And he presents himself before God by confessing the sin he has committed.

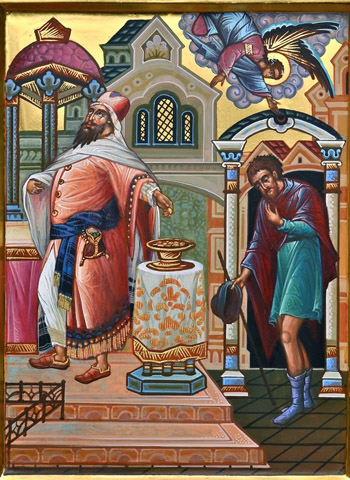

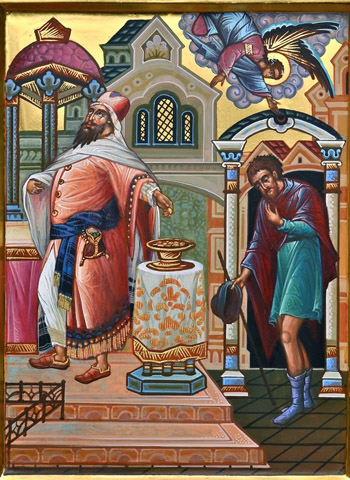

The publican's prayer has this characteristic: He beats his chest and dares not approach the altar, but he has confidence in God – and goes away justified.

On the other hand, the Pharisee does not want to acknowledge his sin, he draws near the altar and it is not with the De Profundis that he addresses God. He approaches the altar and says: I thank you because I am good, that I give alms, etc. In other words, the parable of the Pharisee and the publican (Lk 18:9-14) is an illustration of the presupposition that is in this psalm – in all the penitential psalms, but especially in this one – regarding the matter of being heard by God.

It continues with an argument. It is interesting that this is a prayer that is very well argued. Everything is set out, like the the arguments of a lawyer.

'If Thou, O Lord, wilt mark iniquities: Lord, who shall stand?'

He argues that he understands that God does not want to hear him because of his iniquities. As an aside, I would like to note that I think the word iniquity – by the sound of the word – expresses well the evil that man does. In the word is an onomatopoeia that expresses the malice of sin.

So, let us return to the argument: Lord, I know that You do not want to hear me because of my iniquities, but I have an argument to move You which is this: "’Lord, if you examine iniquities, who will stand?”

So, let us return to the argument: Lord, I know that You do not want to hear me because of my iniquities, but I have an argument to move You which is this: "’Lord, if you examine iniquities, who will stand?”

That is to say, I know that you will not examine everyone because You do not want all to be lost. And if You listen to everyone, You will also listen to the least of all, the most miserable one, myself, for I am still part of that whole, a part of all those whom you want to save. And since you are the Savior, hear me also.

The principle is this. Since You do no longer demand an eye for an eye or a tooth for a tooth, bend this point beyond justice in my favor and hear also me, who acknowledge my great misery.

One can see the admirable beauty of a soul who takes this position, his great humility to recognize God as a Father! And how this way of praying has a stronger reality in the New Testament than in the Old. And in the era of the Reign of Mary, even more than before, will this not be true? For as History progresses, as time goes on, as the Revolution reaches its end and the Counter-Revolution is born, God increasingly shows Himself like this to more and more souls.

The invocation “Lord, Lord” said twice is beautiful. The sinner calls Him Lord, but at the same time this Lord is transformed into something that basically means Father: my Father, my Father.

The invocation “Lord, Lord” said twice is beautiful. The sinner calls Him Lord, but at the same time this Lord is transformed into something that basically means Father: my Father, my Father.

He continues, “For with Thee there is merciful forgiveness: and by reason of Thy law, I have waited for Thee, O Lord.”

That is to say: Lord, You are the seat of clemency, clemency par excellence, You are clemency personified. Knowing this, I turn to You and place my trust in You, because You yourself have commanded me to trust on every occasion.

There is something touching here. Do not call it audacity, because what may seem to be audacity is in fact obedience: Your law commanded me to trust in You at all times, it is a command for everyone, even me, even this most miserable of wretches. No one escapes the empire of Your law, no matter how miserable he is, and this includes me, who obey Your law trusting in You. Here I am.

The logic is such that it seems to me that a lawyer could not devise more beautiful arguments. Coming from the most miserable of men addressed to a splendid, untouchably perfect God, one could not imagine a more magnificent argument than this.

'My soul hath relied on His word: My soul hath hoped in the Lord'

Here he become a little more daring. He says: It is not just Your law, Your honor at stake here. Your word is Your word, You guaranteed it. I trust in Your word, do not deny me. These words have a holy audacity, a beautiful audacity, which is basically an act of trust in the truthfulness of God. He never denies what He Himself has said.

Note the powerful synthesis of the way this is expressed. In a few short words, a whole thinking is present. In fact we are seeing a great soul here, a powerful and immense soul. Although he is miserable, he raises himself up to God in an attitude that, amidst the terrible mess he is in, has something gigantesque. It is the great soul who makes itself small and humbles itself to the final point.

Note the powerful synthesis of the way this is expressed. In a few short words, a whole thinking is present. In fact we are seeing a great soul here, a powerful and immense soul. Although he is miserable, he raises himself up to God in an attitude that, amidst the terrible mess he is in, has something gigantesque. It is the great soul who makes itself small and humbles itself to the final point.

This follows: “From the morning watch even until night, let Israel hope in the Lord.”

What he says is this: The life of the entire chosen nation – all of the Jews, including myself – from morning when we arise to night when we fall asleep, is a continuous act of hope in God. God will answer us, God will help us, God will draw us out of our difficulties. It is the continuous hope and filial trust in the God of the Chosen People, his hope as a member of the Chosen People. Even when the Chosen People have committed such terrible sins, they too must hope in God. When we think that this People have the promise of conversion, we understand the prophetic dimension of the Psalm.

'For with the Lord there is mercy, & with Him plentiful redemption'

He is merciful and the ransom He gives is plentiful. It is so copious that it reaches to the very depths of misery, it reaches me in my mediocrity, my filth, my betrayal, my squalor, in the evil that I placed myself in, mea culpa, mea culpa, mea maxima culpa. Well then, there is that great mercy and it is also for me. No door is closed to anyone and He Himself will redeem Israel from all its iniquities.

That is to say, I will not find in myself the way to redeem myself, but it is God who will rescue me. He will take me away from this dunghill where I am and, despite this, no matter how bad I am, He will raise me up. This is God.

You can see that this final part is very prophetic. There is bountiful redemption and, then, this mercy. The statement that Israel will be redeemed from all iniquities.Very appropriately the Church concludes afterwards: "Glory to the Father, to the Son and to the Holy Spirit." It is the final natural words to close such a magnificent Psalm.

Psalm 129 Vulgate

De profundis clamavi ad te, Domine; Domine, exaudi vocem meam.

Fiant aures tuae intendentes in vocem deprecationis meae.

Si iniquitates observaveris, Domine, Domine, quis sustinebit?

Quia apud te propitiatio est, et propter legem tuam sustinui te, Domine.

Sustinuit anima mea in verbo ejus; speravit anima mea in Domino.

A custodia matutina usque ad noctem, speret Israël in Domino.

Quia apud Dominum misericordia, et copiosa apud eum redemptio.

Et ipse redimet Israel ex omnibus iniquitatibus ejus.

Gloria Patri, et Filio et Spiritui Sancto…

The De Profundis, often prayed for the Souls in Purgatory

It is a prayer for the afflicted on this earth, the afflicted innocent man as well as the afflicted guilty man on this earth, but also for the guilty afflicted souls in the other world, who are the Souls in Purgatory.

All of the Penitential Psalms can be applied to the Souls in Purgatory, but the psalm De Profundis has something special for this purpose.

'Out of the depths have I cried to Thee, O Lord'

The text begins: “Out of the depths I have cried to Thee, O Lord, Lord, hear my voice. Let Thy ears be attentive to the voice of my supplication.”

These two verses make a single whole. The De Profundis well translated is plural and properly means “from the depths,” that is, from various depths. That is to say, from the greatest depths of the depths, from the blackest of afflictions, from the depths of the worst of sins, I have cried to You, O Lord.

From the depths of the greatest infidelity, I have cried to Thee, O Lord

From this realization comes a fear. Will He hear my voice? Then the plea, “Lord, hear my voice.”

This is the first request, which begins the holy circle of pleas and acts of confidence in His mercy. Since I know that my voice cannot be heard because I am so miserable, I begin by first asking that my voice be heard.

This is an act of confidence. I can at least ask to be heard, which is just a tiny bit of mercy that is always within the reach of everyone, even the most miserable, even the most afflicted in unimaginable lost conditions, even the most condemned soul in Purgatory. From these depths one can ask for something: “Lord, hear my voice.”

'Let thy ears be attentive to the voice of my supplication'

Then, he insists on the request: "Let Thy ears be attentive to the voice of my supplication."

Here we have notion of a distracted God who does not want to pay attention, who pretends not to hear, and of a believer, a poor man who knows that God is pretending He does not hear or seems not to hear. But in fact He does. If we insist with Him, He ends up listening. If we humbly ask and ask again and again, He will answer us.

At the crux of his idea of a prodigious separation between God and the sinner – which really does exist – there is also the idea of an infrangible mercy. There is an ear that at least hears when people beg: “Please listen."

The publican is humble & confident & goes away justified

The publican's prayer has this characteristic: He beats his chest and dares not approach the altar, but he has confidence in God – and goes away justified.

On the other hand, the Pharisee does not want to acknowledge his sin, he draws near the altar and it is not with the De Profundis that he addresses God. He approaches the altar and says: I thank you because I am good, that I give alms, etc. In other words, the parable of the Pharisee and the publican (Lk 18:9-14) is an illustration of the presupposition that is in this psalm – in all the penitential psalms, but especially in this one – regarding the matter of being heard by God.

It continues with an argument. It is interesting that this is a prayer that is very well argued. Everything is set out, like the the arguments of a lawyer.

'If Thou, O Lord, wilt mark iniquities: Lord, who shall stand?'

He argues that he understands that God does not want to hear him because of his iniquities. As an aside, I would like to note that I think the word iniquity – by the sound of the word – expresses well the evil that man does. In the word is an onomatopoeia that expresses the malice of sin.

'For with thee there is merciful forgiveness'

That is to say, I know that you will not examine everyone because You do not want all to be lost. And if You listen to everyone, You will also listen to the least of all, the most miserable one, myself, for I am still part of that whole, a part of all those whom you want to save. And since you are the Savior, hear me also.

The principle is this. Since You do no longer demand an eye for an eye or a tooth for a tooth, bend this point beyond justice in my favor and hear also me, who acknowledge my great misery.

One can see the admirable beauty of a soul who takes this position, his great humility to recognize God as a Father! And how this way of praying has a stronger reality in the New Testament than in the Old. And in the era of the Reign of Mary, even more than before, will this not be true? For as History progresses, as time goes on, as the Revolution reaches its end and the Counter-Revolution is born, God increasingly shows Himself like this to more and more souls.

King David address God with confidence, "Lord, Lord'

He continues, “For with Thee there is merciful forgiveness: and by reason of Thy law, I have waited for Thee, O Lord.”

That is to say: Lord, You are the seat of clemency, clemency par excellence, You are clemency personified. Knowing this, I turn to You and place my trust in You, because You yourself have commanded me to trust on every occasion.

There is something touching here. Do not call it audacity, because what may seem to be audacity is in fact obedience: Your law commanded me to trust in You at all times, it is a command for everyone, even me, even this most miserable of wretches. No one escapes the empire of Your law, no matter how miserable he is, and this includes me, who obey Your law trusting in You. Here I am.

The logic is such that it seems to me that a lawyer could not devise more beautiful arguments. Coming from the most miserable of men addressed to a splendid, untouchably perfect God, one could not imagine a more magnificent argument than this.

'My soul hath relied on His word: My soul hath hoped in the Lord'

Here he become a little more daring. He says: It is not just Your law, Your honor at stake here. Your word is Your word, You guaranteed it. I trust in Your word, do not deny me. These words have a holy audacity, a beautiful audacity, which is basically an act of trust in the truthfulness of God. He never denies what He Himself has said.

'I rely on Thy power and Thy Word'

This follows: “From the morning watch even until night, let Israel hope in the Lord.”

What he says is this: The life of the entire chosen nation – all of the Jews, including myself – from morning when we arise to night when we fall asleep, is a continuous act of hope in God. God will answer us, God will help us, God will draw us out of our difficulties. It is the continuous hope and filial trust in the God of the Chosen People, his hope as a member of the Chosen People. Even when the Chosen People have committed such terrible sins, they too must hope in God. When we think that this People have the promise of conversion, we understand the prophetic dimension of the Psalm.

'For with the Lord there is mercy, & with Him plentiful redemption'

He is merciful and the ransom He gives is plentiful. It is so copious that it reaches to the very depths of misery, it reaches me in my mediocrity, my filth, my betrayal, my squalor, in the evil that I placed myself in, mea culpa, mea culpa, mea maxima culpa. Well then, there is that great mercy and it is also for me. No door is closed to anyone and He Himself will redeem Israel from all its iniquities.

That is to say, I will not find in myself the way to redeem myself, but it is God who will rescue me. He will take me away from this dunghill where I am and, despite this, no matter how bad I am, He will raise me up. This is God.

You can see that this final part is very prophetic. There is bountiful redemption and, then, this mercy. The statement that Israel will be redeemed from all iniquities.Very appropriately the Church concludes afterwards: "Glory to the Father, to the Son and to the Holy Spirit." It is the final natural words to close such a magnificent Psalm.

De profundis clamavi ad te, Domine; Domine, exaudi vocem meam.

Fiant aures tuae intendentes in vocem deprecationis meae.

Si iniquitates observaveris, Domine, Domine, quis sustinebit?

Quia apud te propitiatio est, et propter legem tuam sustinui te, Domine.

Sustinuit anima mea in verbo ejus; speravit anima mea in Domino.

A custodia matutina usque ad noctem, speret Israël in Domino.

Quia apud Dominum misericordia, et copiosa apud eum redemptio.

Et ipse redimet Israel ex omnibus iniquitatibus ejus.

Gloria Patri, et Filio et Spiritui Sancto…

A call for mercy & plea for forgiveness

Posted March 22, 2024