Traditionalist Issues

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dialogue Mass - LXXXI

The Change in the 1962 Canon

Presaged the Novus Ordo Mass

The issue at the core of this innovation [of adding St. Joseph to the Canon] is whether the Pope was acting licitly in this regard, against the backdrop of a consensus among his Predecessors, upheld by a tradition of more than a millennium, that nothing should be added to or subtracted from the Canon of the Mass.

In the certain absence of a desire on the part of most Bishops at the Council to even consider any change in so venerable an institution, Pope John XXIII acted on his own initiative in placing St. Joseph in the Canon.

Consternation among the Council Fathers

One witness described the announcement as a “bombshell.” (1) Another stated that “Cardinal Montini later described this unexpected move as ‘a surprise for the Council from the Pope.’ ” (2)

Indeed, no one could have failed to notice that the Canon was instantly deprived of its essential characteristic: immutability.

Even the Anglican Observer, Bernard Pawley, hearing the speech by Bishop Albert Cousineau, (3) who requested this reform at the Council, (4) grasped its inherent message, namely, that “there must be no unchangeable sanctity about the form of words [in the Canon].” (5) He correctly understood its game-changing potential to destroy reverence for the integrity of the Canon of the Mass – a coup for the heirs of the Protestant Reformation.

Nor did most Bishops expect to witness a renunciation by the Pope of the scruple felt by his Predecessors at making the least alteration to it. In fact, support for the innovation among the Council Fathers was conspicuously low key. Although Bishop Cousineau mentioned a recent petition signed by many Church leaders, (6) only 3 Bishops were reported to have actually spoken in favor of it. (7) The Canon, however, cannot be subject to group interests, or altered for subjective reasons or by plebiscite.

Nor did most Bishops expect to witness a renunciation by the Pope of the scruple felt by his Predecessors at making the least alteration to it. In fact, support for the innovation among the Council Fathers was conspicuously low key. Although Bishop Cousineau mentioned a recent petition signed by many Church leaders, (6) only 3 Bishops were reported to have actually spoken in favor of it. (7) The Canon, however, cannot be subject to group interests, or altered for subjective reasons or by plebiscite.

In retrospect, Montini (as Paul VI) made this illuminating comment on 22 January 1968, in one of his many tête-à-têtes with Bugnini:

“You saw, didn’t you, what happened when St. Joseph’s name was introduced into the Canon? First, everyone was against it. Then, one fine morning Pope John decided to insert it and made this known; then, everyone applauded, even those who said they were opposed to it.” (8)

He had calculated shrewdly, as had John XXIII, that once an innovation was approved ‒ or a progressivist document was signed ‒ by the Pope, virtually all of the Bishops who previously opposed it would, as history has shown, become its staunchest defenders. What Pope Paul VI’s remark illuminates is the willingness of most conservative Bishops at the Council to prefer expediency to Tradition, purely for the sake of promoting a contrived show of unity with the Pope of the day, even when he stood in contradiction to it.

Where does the petition come in?

There were many liturgists in the Liturgical Movement who had long been itching to destroy the immutability of the Canon because it represented continuity and permanence, and threatened their plans for liturgical reform. Bugnini, in particular, objected to the lack of “rubrical flexibility” and to the “monolithic” nature of the Canon, (9) while others, as we have seen, had been calling for its reform in various Liturgical Congresses held prior to Vatican II.

John XXIII’s innovation was an endorsement of the most radical reformers whose agenda was to alter the Canon so as to end its unchangeable nature. Under the camouflage of the petition, John XXIII could satisfy their demands without being seen to do so.

John XXIII’s innovation was an endorsement of the most radical reformers whose agenda was to alter the Canon so as to end its unchangeable nature. Under the camouflage of the petition, John XXIII could satisfy their demands without being seen to do so.

We will now consider a few further points which call into question the value and legitimacy of the entire project.

Some say that a single addition to the Canon is trivial, and that objectors must be small-minded, “Pharisaical” people with a penchant for keeping to the strict letter of the law. In fact, it matters crucially because the Canon is a fixed formula of prayer that flows directly from the lex orandi of the early Christian centuries. Its value consists in a liturgical restatement of the unchanging doctrine of the Mass as understood in the Church since the beginning of Christianity. Thus, it guarantees the truth of all the other prayers of the Mass.

Change the Canon, then nothing in the Mass would ever be firmly established or free from further interference.

A changed Canon is no Canon

The word Canon came from the Greek kanon, which meant a reed or cane used as a measuring tool; figuratively it came to mean a norm, rule or standard of excellence which was both authoritative and binding. So, by its very name and nature, the Canon was set in metaphorical stone as the unchanging rule of prayer surrounding the confection of the Eucharist.

Fr. Nikolaus Gihr explained the reason for its immutability:

“As the Sacrifice, which the eternal High Priest offers on the altar to the end of ages, is and ever remains the same, so, in like manner the Canon, the ecclesiastical sacrificial prayer, in its sublime simplicity and venerable majesty, is and ever remains invariably the same.” (10)

“As the Sacrifice, which the eternal High Priest offers on the altar to the end of ages, is and ever remains the same, so, in like manner the Canon, the ecclesiastical sacrificial prayer, in its sublime simplicity and venerable majesty, is and ever remains invariably the same.” (10)

That was the simple truth understood and defended by orthodox Catholics down the centuries. It would be simply unconscionable to change something that was considered to be “through its origin, antiquity and use, venerable and inviolable and sacred.” (11)

But, it was precisely this non-negotiable inflexibility that 20th century progressivist reformers wanted to remove as an obstacle to their plans. However, the Canon is not an instrument for supporting agendas or promoting personal wishes even if favored by a particular Pope.

Crossing the red line

Before John XXIII’s innovation, no Pope had ever ventured to introduce into the Canon an extraneous element, i.e., one that was not already in use in the early centuries of liturgical development. Not even Pope Gregory I (who, we are told, “added” extra words to the Hanc igitur of the Canon (12) in the 6th century) altered this tradition.

As Fr. Fortescue pointed out, the Hanc igitur was originally a variable prayer and Pope Gregory gave it a fixed formula, using prayers taken from the Mass itself. (13) Thus, there was no question of inserting a novelty into the

Hanc igitur, for Pope Gregory I’s words were but a partial reduplication of prayers for the living and the dead found in other parts of the Mass. (14) These words, then, were not so much an addition as a replacement in one succinct phrase for all the individual intentions of the faithful that the priest formerly mentioned at this point in the Canon. (15)

As Fr. Fortescue pointed out, the Hanc igitur was originally a variable prayer and Pope Gregory gave it a fixed formula, using prayers taken from the Mass itself. (13) Thus, there was no question of inserting a novelty into the

Hanc igitur, for Pope Gregory I’s words were but a partial reduplication of prayers for the living and the dead found in other parts of the Mass. (14) These words, then, were not so much an addition as a replacement in one succinct phrase for all the individual intentions of the faithful that the priest formerly mentioned at this point in the Canon. (15)

Unlike John XXIII and the Vatican II Popes, Gregory I was an organizer, not an innovator.

We will now examine some of the weighty reasons – philosophical, theological and liturgical – for considering John XXIII’s innovation to be unjustified.

According to St. Thomas Aquinas, for an act to be right or reasonable it must not be inherently flawed, i.e., contain anything contrary to its nature. The Canon is unchangeable because it can in no way become other than it is without ceasing to be true to itself and becoming potentially subject to further change.

Once the principle of immutability had been breached by John XXIII in the Canon, everything else in the Mass becomes changeable, with the result that change is the only thing that becomes fixed. The 1962 Canon was, thus, the major impetus for the ever-evolving liturgies of the Novus Ordo.

Nor is it enough for an act to be good in one point only; it must be good in every respect. It would be wrong, for example, to destroy a basic good (the immutability of the Canon) for the purpose of bringing about another instance of a basic good (veneration of St. Joseph). Aquinas would have considered that “repugnant to right reason.”

The scourge of legal positivism

Implicit in Pope John XXIII’s innovation is the notion that there was nothing intrinsically valuable about immutability as far as the Canon was concerned. The key fact remains that the immutable rule of prayer has been breached by a personal intervention of a Pope who refused to accept the constraints of all his Predecessors, preferring to be guided by his own predilections.

As in all cases of legal positivism, of which this is a classic example, it is simply assumed that any papal legislation is licit, not because it is rooted in reason or natural law, but because it is enacted by legitimate authority.

We have St. Thomas’s assurance that a just law must be reasonable or based in reason, and not merely in the will of the legislator. Therefore, the exercise of discretionary powers has to be reasoned, otherwise it is arbitrary.

When we consider that John XXIII was influenced by extraneous and irrelevant factors that were given in support of his decision – such as his own personal devotion to St. Joseph and the demands of pressure groups presented in the form of a petition – it is reasonable to assume that he was acting ultra vires and that his action was illicit.

A better way to honor St. Joseph would have been to restore his Octave abolished in 1956.

Continued

In the certain absence of a desire on the part of most Bishops at the Council to even consider any change in so venerable an institution, Pope John XXIII acted on his own initiative in placing St. Joseph in the Canon.

Consternation among the Council Fathers

One witness described the announcement as a “bombshell.” (1) Another stated that “Cardinal Montini later described this unexpected move as ‘a surprise for the Council from the Pope.’ ” (2)

Indeed, no one could have failed to notice that the Canon was instantly deprived of its essential characteristic: immutability.

Even the Anglican Observer, Bernard Pawley, hearing the speech by Bishop Albert Cousineau, (3) who requested this reform at the Council, (4) grasped its inherent message, namely, that “there must be no unchangeable sanctity about the form of words [in the Canon].” (5) He correctly understood its game-changing potential to destroy reverence for the integrity of the Canon of the Mass – a coup for the heirs of the Protestant Reformation.

Card. Roncalli and Card. Montini were allies,

and ordered Bugnini to reform the Mass

In retrospect, Montini (as Paul VI) made this illuminating comment on 22 January 1968, in one of his many tête-à-têtes with Bugnini:

“You saw, didn’t you, what happened when St. Joseph’s name was introduced into the Canon? First, everyone was against it. Then, one fine morning Pope John decided to insert it and made this known; then, everyone applauded, even those who said they were opposed to it.” (8)

He had calculated shrewdly, as had John XXIII, that once an innovation was approved ‒ or a progressivist document was signed ‒ by the Pope, virtually all of the Bishops who previously opposed it would, as history has shown, become its staunchest defenders. What Pope Paul VI’s remark illuminates is the willingness of most conservative Bishops at the Council to prefer expediency to Tradition, purely for the sake of promoting a contrived show of unity with the Pope of the day, even when he stood in contradiction to it.

Where does the petition come in?

There were many liturgists in the Liturgical Movement who had long been itching to destroy the immutability of the Canon because it represented continuity and permanence, and threatened their plans for liturgical reform. Bugnini, in particular, objected to the lack of “rubrical flexibility” and to the “monolithic” nature of the Canon, (9) while others, as we have seen, had been calling for its reform in various Liturgical Congresses held prior to Vatican II.

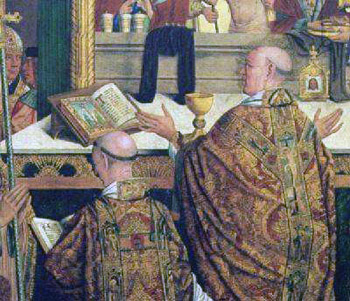

The Canon, a centuries-old fixed formula of prayer

We will now consider a few further points which call into question the value and legitimacy of the entire project.

Some say that a single addition to the Canon is trivial, and that objectors must be small-minded, “Pharisaical” people with a penchant for keeping to the strict letter of the law. In fact, it matters crucially because the Canon is a fixed formula of prayer that flows directly from the lex orandi of the early Christian centuries. Its value consists in a liturgical restatement of the unchanging doctrine of the Mass as understood in the Church since the beginning of Christianity. Thus, it guarantees the truth of all the other prayers of the Mass.

Change the Canon, then nothing in the Mass would ever be firmly established or free from further interference.

A changed Canon is no Canon

The word Canon came from the Greek kanon, which meant a reed or cane used as a measuring tool; figuratively it came to mean a norm, rule or standard of excellence which was both authoritative and binding. So, by its very name and nature, the Canon was set in metaphorical stone as the unchanging rule of prayer surrounding the confection of the Eucharist.

Fr. Nikolaus Gihr explained the reason for its immutability:

The Canon: 'ever remains invariably the same'

That was the simple truth understood and defended by orthodox Catholics down the centuries. It would be simply unconscionable to change something that was considered to be “through its origin, antiquity and use, venerable and inviolable and sacred.” (11)

But, it was precisely this non-negotiable inflexibility that 20th century progressivist reformers wanted to remove as an obstacle to their plans. However, the Canon is not an instrument for supporting agendas or promoting personal wishes even if favored by a particular Pope.

Crossing the red line

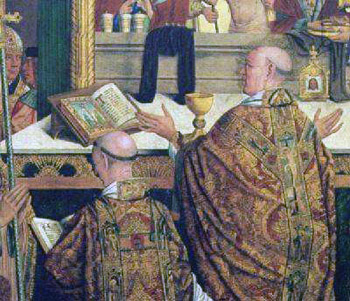

Before John XXIII’s innovation, no Pope had ever ventured to introduce into the Canon an extraneous element, i.e., one that was not already in use in the early centuries of liturgical development. Not even Pope Gregory I (who, we are told, “added” extra words to the Hanc igitur of the Canon (12) in the 6th century) altered this tradition.

Our Lord appears to St. Gregory the Great while saying the Canon of the Mass

Unlike John XXIII and the Vatican II Popes, Gregory I was an organizer, not an innovator.

We will now examine some of the weighty reasons – philosophical, theological and liturgical – for considering John XXIII’s innovation to be unjustified.

According to St. Thomas Aquinas, for an act to be right or reasonable it must not be inherently flawed, i.e., contain anything contrary to its nature. The Canon is unchangeable because it can in no way become other than it is without ceasing to be true to itself and becoming potentially subject to further change.

Once the principle of immutability had been breached by John XXIII in the Canon, everything else in the Mass becomes changeable, with the result that change is the only thing that becomes fixed. The 1962 Canon was, thus, the major impetus for the ever-evolving liturgies of the Novus Ordo.

Nor is it enough for an act to be good in one point only; it must be good in every respect. It would be wrong, for example, to destroy a basic good (the immutability of the Canon) for the purpose of bringing about another instance of a basic good (veneration of St. Joseph). Aquinas would have considered that “repugnant to right reason.”

The scourge of legal positivism

Implicit in Pope John XXIII’s innovation is the notion that there was nothing intrinsically valuable about immutability as far as the Canon was concerned. The key fact remains that the immutable rule of prayer has been breached by a personal intervention of a Pope who refused to accept the constraints of all his Predecessors, preferring to be guided by his own predilections.

As in all cases of legal positivism, of which this is a classic example, it is simply assumed that any papal legislation is licit, not because it is rooted in reason or natural law, but because it is enacted by legitimate authority.

We have St. Thomas’s assurance that a just law must be reasonable or based in reason, and not merely in the will of the legislator. Therefore, the exercise of discretionary powers has to be reasoned, otherwise it is arbitrary.

When we consider that John XXIII was influenced by extraneous and irrelevant factors that were given in support of his decision – such as his own personal devotion to St. Joseph and the demands of pressure groups presented in the form of a petition – it is reasonable to assume that he was acting ultra vires and that his action was illicit.

A better way to honor St. Joseph would have been to restore his Octave abolished in 1956.

Continued

- Henri Fesquet, the religious affairs correspondent for the Paris newspaper, Le Monde, and its special envoy in Rome, wrote: “A bombshell fell on the general congregation Tuesday. Cardinal Cicognani, Secretary of State, announced that the Pope has decided to insert the name of Saint Joseph after that of the Virgin Mary in the Canon of the Mass.” The Drama of Vatican II: The Ecumenical Council June 1962- December 1965, Random House, 1967, p. 69.

- Ralph Wiltgen, The Rhine Flows Into the Tiber, Hawthorn Books, 1967, p. 45.

- Canadian Bishop Albert Cousineau C.S.C. was Bishop of Cap Haitien, Haiti, and a former Rector of St Joseph’s Oratory, Montreal, which was one of several centres campaigning to have St Joseph’s name in the Canon of the Mass.

- For a record of his speech (in Latin), see Synodalia, vol. 1, First Period, Part 2, 5 November 1962, Typis Polyglottis Vaticanis, 1970, Congregatio Generalis XII, pp. 119-120.

- Bernard C. Pawley, Observing Vatican II : The Confidential Reports of the Archbishop of Canterbury’s Representative, Bernard Pawley, 1961-1964, Cambridge University Press, 2013, p. 153.

- Their identities were not revealed. As part of an organized campaign, the petition was presented to Pope John XXIII in March 1962, which included signatures of Bishops and Archbishops, asking for the name of St. Joseph to be inserted into the Mass wherever the name of the Blessed Virgin is mentioned. Fr Ralph Wiltgen reported that “While examining these signatures, Pope John XXIII said, ‘Something will be done for St. Joseph.’” (The Rhine Flows into the Tiber, p. 46)

- These were Auxiliary Bishop Ildefonso Sansierra of San Juan de Cuyo, Argentina, Bishop Albert Cousineau, C.S.C. of Cap Haitien, Haiti, and Bishop Petar Cule, of Mostar, Yugoslavia.

- A. Bugnini, The Reform of the Liturgy 1948-1975, p. 369, note 30.

- Ibid., p. 448.

- Nikolaus Gihr, The Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, St Louis: Herder, 1902, p. 581. Fr. Gihr added that “only on the greatest feasts are a few additions made in order to harmonize with the spirit and change of the ecclesiastical year.”

- Ibid., p. 579.

- These words were diesque nostros in tua pace disponas (and order our days in Thy peace).

- Fortescue, The Mass, p. 155.

- E.g., the Commemoration of the Dead; also the Libera nos and the Nobis quoque, which speak of peace in this life and salvation in the next.

- In earlier times, it was customary for the priest or deacon to read aloud the names and intentions of some of the faithful.

Posted January 21, 2019

______________________

______________________

Volume I |

Volume II |

Volume III |

Volume IV |

Volume V |

Volume VI |

Volume VII |

Volume VIII |

Volume IX |

Volume X |

Volume XI |

Special Edition |