Movie Review

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Problems with Disney's Coco - Part 2

The Catholic Origins of Día de los Muertos

After considering the paganized version of Día de los Muertos presented in the film Coco, what is the real story behind Día de los Muertos (All Souls Day, November 2)? First, let us consider the history of the evangelization of Mexico, the purification of its customs, and the backdrop of events in Europe.

As a prize for its 800-year-long Reconquista against Islam, God allowed Spain and Portugal to expand their empires and extend Christendom across the vast expanse of water that separates Europe and the Americas, in order to conquer souls for the Church and to spread Catholic Civilization.

As a prize for its 800-year-long Reconquista against Islam, God allowed Spain and Portugal to expand their empires and extend Christendom across the vast expanse of water that separates Europe and the Americas, in order to conquer souls for the Church and to spread Catholic Civilization.

In the year 1519, Hernán Cortés and his Spanish conquistadores arrived at the shores of what is now Mexico. This, along with the important apparition of Our Lady of Guadalupe only 11 years later in 1531, would be the beginning of the conversion of the various indigenous peoples of Mexico and the Americas, and this conversion would necessarily bring a purification of the people’s customs.

This conversion and purification of customs is not something that happens overnight. The Church in her wisdom always respects the local customs of those recently-converted peoples, and finds ways to give them Catholic meaning while removing their pagan elements. If we consider the history of the European peoples and their initiation into the Faith, we see that it took many centuries to purify the pagan elements of their customs in order to produce the Catholic Civilization of Europe, whose high point was the Middle Ages.

While most of Europe became infected with the Revolution at the end of the Middle Ages, which sought to dethrone God and place man in His stead, Spain and Portugal were busy fighting the Muslims, and were not as infected with this Revolutionary virus. This is why God allowed these two great nations to expand their empires to the New World.

Thus, the Revolution had already been born when Mexico received the Catholic Faith.

It was the influence of the Masonic principles of the French Revolution that caused Mexico to proclaim independence from Spain, preventing Mexico from reaching the civilization it could have reached without this bad influence.

It was the influence of the Masonic principles of the French Revolution that caused Mexico to proclaim independence from Spain, preventing Mexico from reaching the civilization it could have reached without this bad influence.

These Masons who have infiltrated the Latin peoples are working very hard to encourage Tribalism, the Fourth Revolution, and since Vatican II, with the cooperation of the clergy the corruption of customs is descending to deep abysses This influence of Tribalism is why many pagan customs are seeing a revival.

Thus, despite the admirable, colorful and rich customs of Catholic Mexico, it can be affirmed that some of the customs of the Mexican people were never fully purified of all their pagan elements. Even worse, these past remnants of paganism are being revived and re-stoked. We have the hope that this may be remedied in the Reign of Mary, and that the Mexican people may give the full glory to God that is His due in society.

The Catholic customs of Día de los Muertos

With this historical background in mind, let us consider the customs of the real Día de los Muertos, and then see how a Catholic should respond to the current re-paganization of this feast.

With this historical background in mind, let us consider the customs of the real Día de los Muertos, and then see how a Catholic should respond to the current re-paganization of this feast.

The Mexicans took the Days of the Dead (November 1 and 2) very seriously, setting up special altars (ofrendas) in their homes to remember the Saints and the deceased members of their families. November 1 (All Saints Day), known as “Día de los Inocentes,” was seen as a day to commemorate deceased children and infants. All Souls Day (November 2) was the day to honor the deceased adults in the family.

It was an old belief in many countries that the souls of the dead children and adults would visit earth on their designated day (See “Ringing the Bells for All Saints Day”). The Catholic Church did not condemn this belief.1

Altars for the dead or ofrendas

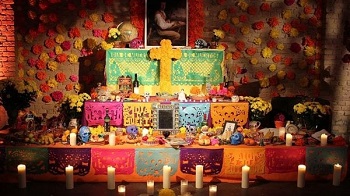

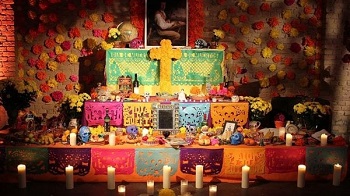

The ofrendas2 would often have at least three tiers with images of Saints and deceased family members, skulls, calaveras (handmade skeleton figures), bread, salt, water, harvest fruits, sugar skulls, sweets and breads, marigolds and other flowers symbolizing the brevity of life, colorful paper banners, and one candle for every dead family member.

The ofrendas2 would often have at least three tiers with images of Saints and deceased family members, skulls, calaveras (handmade skeleton figures), bread, salt, water, harvest fruits, sugar skulls, sweets and breads, marigolds and other flowers symbolizing the brevity of life, colorful paper banners, and one candle for every dead family member.

The candles represent faith and hope, burning through the night to give hope to the souls. One extra candle is also lit for any forgotten dead. Lighting candles for the dead or in honor of Saints has always been a Catholic custom,, as in Poland where cemeteries became seas of light.

Many Mexicans believed that on October 31, the souls of dead children would return to their former homes. To welcome these children called angelitos, families would lay one lighted candle and gourd filled with favorite foods and flowers for every angelito. Often little altars were set up to hold the food and an image of the child’s patron saint was placed on the altar.

The Church began the first steps of purification with this originally animist custom of setting aside food for the dead by encouraging the people to distribute the food set aside for the dead to the poor.3 Thus this act of charity became an efficacious means to help the souls in Purgatory, rather than to appease them or sustain them in the after-life.

When the peoples converted, they still maintained the belief that the souls came back, but they understood that these souls were from Purgatory asking for prayers. The belief that some souls in Purgatory did some of their penance on earth was held by many Church doctors such as St. Augustine.4

When the peoples converted, they still maintained the belief that the souls came back, but they understood that these souls were from Purgatory asking for prayers. The belief that some souls in Purgatory did some of their penance on earth was held by many Church doctors such as St. Augustine.4

The Church took an active part in directing this attention away from the pagan aspects of this festival. In parts of Mexico, women spent all night praying for the poor souls in the cemetery on All Hallows Eve; priests said Masses in the cemetery chapel in the early morning. Coffins were set up in the church and filled with offerings of pumpkins, corn, squash, fruit, candles and other food that would later be distributed to the poor. After Mass, the priest walked by the coffins sprinkling them with incense and holy water. (Fiesta in Mexico, p. 213)

On Día de los Muertos, Mexicans went early before dawn to the cemeteries carrying flowers and candles to adorn the graves, and skull-shaped brightly colored breads, cakes, candied pumpkin and sweets for a picnic by the family grave. One traditional bread is Pan de Muerto [Bread of the Dead Man] which often has a tiny skeleton inside that is said to bring blessings to the finder. The priest would often walk through the cemetery sprinkling graves with holy water. Many Mexican families kept an all-night vigil by the candlelit graves of their loved ones, praying, feasting, singing, and retelling stories of their dead family members.

Catholicizing pagan elements

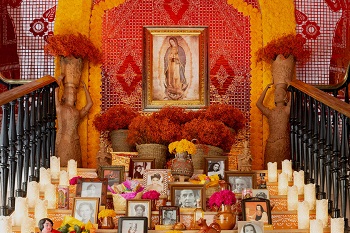

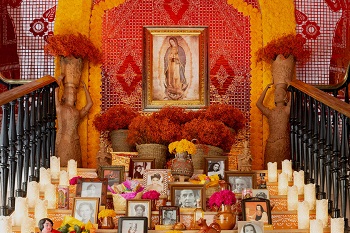

Although many Mexicans have retained remnants of pagan customs, it seems that these could be Catholicized: primary images and statues on the altars could be Our Lord, Our Lady, and the Patron Saints of the deceased with small images of family members, rosaries and blessed candles burning in the holy souls' honor. Food placed on the altars could be given as alms to the poor to relieve the holy souls. The primary focus of all of these customs ought to be to remember the poor souls, specifically by praying and offering alms for them.

Although many Mexicans have retained remnants of pagan customs, it seems that these could be Catholicized: primary images and statues on the altars could be Our Lord, Our Lady, and the Patron Saints of the deceased with small images of family members, rosaries and blessed candles burning in the holy souls' honor. Food placed on the altars could be given as alms to the poor to relieve the holy souls. The primary focus of all of these customs ought to be to remember the poor souls, specifically by praying and offering alms for them.

The custom of Mexican men “souling” is an excellent way the Church Catholicized a popular practice. In parts of Mexico, groups of men and boys would go from house to house, ringing bells from the local parish church and chanting, “Here come the blessed souls” to beg for food left on the altars of the dead. They were warmly received and given gifts of food. Thus, the food given in honor of the deceased would give true relief to the holy souls as alms.

We close this article with the words of one of the charming souling songs (Fiesta in Mexico, p. 215):

“Give me freedom, Lord, of this village to adore Thee,

And a true love, to go to heaven to enjoy Thee.”

Continued

Continued

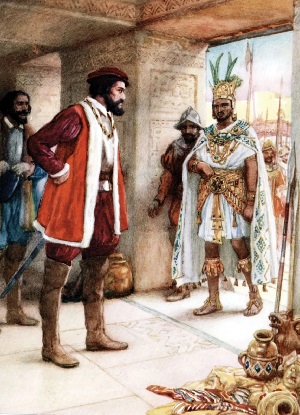

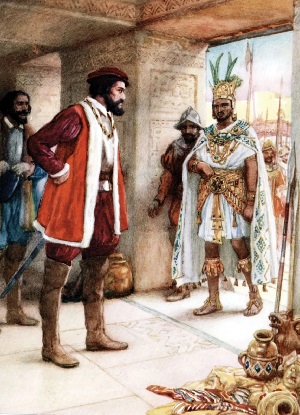

Above, Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar gives Cortés command of the expedition to Mexico; below: Hernan Cortes meets Montezuma II. Source here & here

In the year 1519, Hernán Cortés and his Spanish conquistadores arrived at the shores of what is now Mexico. This, along with the important apparition of Our Lady of Guadalupe only 11 years later in 1531, would be the beginning of the conversion of the various indigenous peoples of Mexico and the Americas, and this conversion would necessarily bring a purification of the people’s customs.

This conversion and purification of customs is not something that happens overnight. The Church in her wisdom always respects the local customs of those recently-converted peoples, and finds ways to give them Catholic meaning while removing their pagan elements. If we consider the history of the European peoples and their initiation into the Faith, we see that it took many centuries to purify the pagan elements of their customs in order to produce the Catholic Civilization of Europe, whose high point was the Middle Ages.

While most of Europe became infected with the Revolution at the end of the Middle Ages, which sought to dethrone God and place man in His stead, Spain and Portugal were busy fighting the Muslims, and were not as infected with this Revolutionary virus. This is why God allowed these two great nations to expand their empires to the New World.

Thus, the Revolution had already been born when Mexico received the Catholic Faith.

The majestic Palace of Hernán Cortés, built between 1523-1528, Cuernavaca, Mexico

These Masons who have infiltrated the Latin peoples are working very hard to encourage Tribalism, the Fourth Revolution, and since Vatican II, with the cooperation of the clergy the corruption of customs is descending to deep abysses This influence of Tribalism is why many pagan customs are seeing a revival.

Thus, despite the admirable, colorful and rich customs of Catholic Mexico, it can be affirmed that some of the customs of the Mexican people were never fully purified of all their pagan elements. Even worse, these past remnants of paganism are being revived and re-stoked. We have the hope that this may be remedied in the Reign of Mary, and that the Mexican people may give the full glory to God that is His due in society.

The Catholic customs of Día de los Muertos

Juan Diego unfolds his tilma to the Bishop, the image of Our Lady of Guadalupe appears miraculously

The Mexicans took the Days of the Dead (November 1 and 2) very seriously, setting up special altars (ofrendas) in their homes to remember the Saints and the deceased members of their families. November 1 (All Saints Day), known as “Día de los Inocentes,” was seen as a day to commemorate deceased children and infants. All Souls Day (November 2) was the day to honor the deceased adults in the family.

It was an old belief in many countries that the souls of the dead children and adults would visit earth on their designated day (See “Ringing the Bells for All Saints Day”). The Catholic Church did not condemn this belief.1

Altars for the dead or ofrendas

The candles represent faith and hope, burning through the night to give hope to the souls. One extra candle is also lit for any forgotten dead. Lighting candles for the dead or in honor of Saints has always been a Catholic custom,, as in Poland where cemeteries became seas of light.

Many Mexicans believed that on October 31, the souls of dead children would return to their former homes. To welcome these children called angelitos, families would lay one lighted candle and gourd filled with favorite foods and flowers for every angelito. Often little altars were set up to hold the food and an image of the child’s patron saint was placed on the altar.

The Church began the first steps of purification with this originally animist custom of setting aside food for the dead by encouraging the people to distribute the food set aside for the dead to the poor.3 Thus this act of charity became an efficacious means to help the souls in Purgatory, rather than to appease them or sustain them in the after-life.

Typical ofrendas made for deceased family members

The Church took an active part in directing this attention away from the pagan aspects of this festival. In parts of Mexico, women spent all night praying for the poor souls in the cemetery on All Hallows Eve; priests said Masses in the cemetery chapel in the early morning. Coffins were set up in the church and filled with offerings of pumpkins, corn, squash, fruit, candles and other food that would later be distributed to the poor. After Mass, the priest walked by the coffins sprinkling them with incense and holy water. (Fiesta in Mexico, p. 213)

On Día de los Muertos, Mexicans went early before dawn to the cemeteries carrying flowers and candles to adorn the graves, and skull-shaped brightly colored breads, cakes, candied pumpkin and sweets for a picnic by the family grave. One traditional bread is Pan de Muerto [Bread of the Dead Man] which often has a tiny skeleton inside that is said to bring blessings to the finder. The priest would often walk through the cemetery sprinkling graves with holy water. Many Mexican families kept an all-night vigil by the candlelit graves of their loved ones, praying, feasting, singing, and retelling stories of their dead family members.

Catholicizing pagan elements

Another elaborate many-tiered ofrenda

The custom of Mexican men “souling” is an excellent way the Church Catholicized a popular practice. In parts of Mexico, groups of men and boys would go from house to house, ringing bells from the local parish church and chanting, “Here come the blessed souls” to beg for food left on the altars of the dead. They were warmly received and given gifts of food. Thus, the food given in honor of the deceased would give true relief to the holy souls as alms.

We close this article with the words of one of the charming souling songs (Fiesta in Mexico, p. 215):

And a true love, to go to heaven to enjoy Thee.”

-

Main source: Erna Fergusson, Fiesta in Mexico (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1934)

- In his Summa Theologiae, Question 69, Article 3, St. Thomas affirms: “According to the disposition of

Divine Pprovidence, separated souls at times come forth from their abode and appear to

men, as Augustine, in the book quoted above, relates how

martyr Felix appeared visibly to the people of Nola when they were besieged by the barbarians. It is also credible that the damned might also be allowed to appear for

man's instruction and intimidation; or again some might be permitted to appear in order to seek our suffrages, as to those who are detained in purgatory, as evidenced by many instances related in the fourth book of the Dialogues.”

Regarding the above quote of St. Thomas Aquinas, the Catholic website Fisheaters explains: “The Church teaches that God may well allow a departed human soul to pay a visit to the living. Some of these spirits may be Saints (those in Heaven, canonized or not). Some may be purgatorial spirits. God may let purgatorial souls - the souls of those who need to be purified before they enter into Heaven - appear so that we will be warned, or reminded to pray for them. And some may be damned. She teaches, too, however, that demons can and do mimic departed human spirits, and that it is sinful to initiate contact with the departed.” - "Throughout the first two days of November, all the doors of the house remain open to encourage visitors from all over town to participate in the celebration and to visit the family shrine." ( Gaceta Consular. Number 25, Year IV, Austin, Texas. 1996)

- “The next day all the food is presented to friends and neighbors or given to beggars; it is always eaten, but never by the family that prepared it. It is customary to invite friends to ‘pass by.’ The callers bring food and are offered part of what the family has.” (Fiesta in Mexico, p. 201).

- “As S. Augustine said: Sometimes souls are punished in the places where they have sinned, as appears in an example that St. Gregory recited in the fourth book of his Dialogues. He said that there was a priest who used gladly a bath, and when he came into the bath he found a man whom he knew was always ready to serve him. And it happed that for his diligent service and his reward, the priest gave to him a holy loaf. And he weeping, answered: Father, wherefore givest thou me this thing? I may not eat it for it is holy. I was once lord of this place, but after my death, I was deputed to serve here for my sins, but I pray thee that thou wilt offer this bread unto Almighty God for my sins, and know thou for certain that thy prayer shall be heard, and when then thou shalt come to wash thee, thou shalt not find me. And then this priest offered a week's entire sacrifice to God for him, and when he came again he found him not.” (The Golden Legend)

Posted October 30, 2024

______________________

______________________