Traditionalist Issues

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dialogue Mass - CXLIII

Ratzinger’s Lutheran Doctrine on the

Real Presence

“Nam et loquela tua manifestum te facit”: (Matt.26:73) (Even your speech gives you away)

Ratzinger’s objection to the “crystal clear” language of Scholasticism, coupled with his inveterate scorn for the “Manualist tradition,” suggests an intention (shared by all the neo-modernists) to detach himself not only from the form of Catholic theology, but also from its substance. That intention was deftly camouflaged in Pope John XXIII’s Opening Speech of the Council with his well-known platitude:

“The substance of the ancient doctrine of the deposit of faith is one thing, and the way in which it is presented, with the same meaning and judgment, is another.”

But if the substance of the Faith has no essential relation to the way it is presented, i.e., to the language in which it is expressed, as John XXIII’s aphorism seems to imply, we cannot even begin to talk about the “same meaning and judgment” because there would be no objective linguistic criteria with which to establish what is true or not true. We would simply lose the capacity to transmit with certainty the ontological truth about “being” (“what is”) – especially the Supreme Being (“I Am”, Exodus 3:14) – and its meaning.

This is precisely where Scholasticism comes in – to provide the Church with a universal standard of expression with which she can present the immutable Truth in a logical and coherent manner regardless of time or place. With the demise of Scholasticism, it is obvious that we have become the mere playthings of theologians and reformers who wish to impose their own meanings through the use of language calculated to manipulate our minds.

This is precisely where Scholasticism comes in – to provide the Church with a universal standard of expression with which she can present the immutable Truth in a logical and coherent manner regardless of time or place. With the demise of Scholasticism, it is obvious that we have become the mere playthings of theologians and reformers who wish to impose their own meanings through the use of language calculated to manipulate our minds.

It was common practice among progressivist theologians at the Council, including Fr. Ratzinger, to reject the original schemas which had been prepared by their conservative counterparts. In reformulating the language of the schema on the Constitution of the Church, for example, Ratzinger showed his determination not to keep to the same meaning as the original document:

“The new text describes the relationship between the Church and non-Catholic Christians without speaking of ‘membership.’ By shedding this terminological armour, the text acquired a much wider scope.” 1

As a theologian, Ratzinger shared much in common with his fellow neo-modernists of the Vatican II era in his aversion to the “fixed formulas” of Scholasticism on a whole range of substantial truths of Catholicism relating to the concept of “being.” These included the traditional teaching on the Real Presence, the nature of the Church as a monarchical institution, Revelation as definitively closed, the indissolubility of marriage and other defined dogmas which are unacceptable especially to Protestants. Ratzinger’s scepticism on all these issues is documented at various points throughout these articles.

Because of the seriousness of the subject, and the desire to be scrupulously accurate, we will take the original source of Ratzinger’s statements as written in the German versions, before they were somewhat laundered in later translations. The emphasis will be placed not on what he himself personally believed – this is difficult to ascertain because of the ambiguities and circumlocutions of his style – but on the content of his statements and how he presented them.

The Real Presence

Of all the areas of Catholic doctrine in which the absence of Scholastic thinking is most keenly felt, it must surely be the doctrine of the Real Presence. When Paul VI published his Encyclical Mysterium Fidei in 1965, he recognized that there was a crisis of belief in the Eucharist, especially in the Real Presence. He laid the blame in large part at the door of those who in spoken and written word “spread abroad opinions which disturb the faithful and fill their minds with no little confusion about matters of faith.” (§ 10)

he situation could not be more ironic: one of the theologians in question, a young academic named Fr. Joseph Ratzinger (who would eventually become one of Paul VI’s successors) was at that time busy spreading confusion about the Real Presence with subtle and convoluted theories. In 1966, Ratzinger wrote the following:

“Eucharistic adoration or the silent visit in a church cannot reasonably be just a conversation with the God who is thought [sic] to be locally present in a confined space. Statements like ‘God lives here’ and the conversation with the God who is thought [sic] to be locally present in this way express a misunderstanding of the Christological mystery such as the concept of God, which necessarily repels the thinking person who knows about God’s omnipresence.

“Eucharistic adoration or the silent visit in a church cannot reasonably be just a conversation with the God who is thought [sic] to be locally present in a confined space. Statements like ‘God lives here’ and the conversation with the God who is thought [sic] to be locally present in this way express a misunderstanding of the Christological mystery such as the concept of God, which necessarily repels the thinking person who knows about God’s omnipresence.

"If one wanted to justify going to church by saying that one had to visit the God who is only present there, then this would in fact be a reason that made no sense, and would be rightly rejected by modern people.” 2

The whole passage raises a question which should never occur to a true Catholic: Is Christ really present in the tabernacle, or just thought by some to be there? In other words, is the Real Presence just a figment of some people’s imagination? These remarks, first published in 1966, inevitably caused a certain amount of scandal amongst the faithful, and there was a backlash of outraged criticism of their author. Nowadays, they are more likely to be greeted with shrug of indifference.

In response, Ratzinger tried to justify himself in a later publication, God is near us, by saying that there had been “a misapprehension” by his critics, and that his remarks do not deny the Real Presence or oppose adoration.3 However, in the normal understanding of his words, they certainly seemed to imply both.

Furthermore, the passage ignores what the Church has taught about the unique status of Christ’s presence in the Eucharist. It has always been believed that, although God is everywhere (and had been so before the Incarnation), He is sacramentally present in the Eucharist in the fullness of His corporeal nature (Body and Blood) as well in His spiritual nature (Soul and Divinity).

Furthermore, the passage ignores what the Church has taught about the unique status of Christ’s presence in the Eucharist. It has always been believed that, although God is everywhere (and had been so before the Incarnation), He is sacramentally present in the Eucharist in the fullness of His corporeal nature (Body and Blood) as well in His spiritual nature (Soul and Divinity).

The 19th-century Oratorian priest, Fr. Frederick William Faber, for example, had no difficulty in accepting the presence of the “Eternal, Incomprehensible, Almighty Word who is everywhere and yet fixed there,” yet Who chooses to reside in “the quiet modesty of the Blessed Sacrament.” 4 It is not just modern man who rejects this teaching – the initial complaint (John 6:61) against it has been reiterated since Our Lord’s times: “This is intolerable language. Who could accept it?”

Transubstantiation is not a subject for ‘dialogue’

Pope Benedict XVI later reformulated the doctrine of transubstantiation in terms that not only eviscerated the Eucharist of its meaning but, on more than one occasion, strayed into the Protestant camp, if his words are to be judged according to the solemn definition of the Council of Trent.

During his tenure of the papal office, for instance, he wrote a trilogy on Jesus of Nazareth (reviewshere and here), making a point of publishing it under his own name; he explained the reason in the Preface to Volume 1: It was “in no way a magisterial act, but rather an expression of my personal search ‘for the face of the Lord.’ (Ps 27:8)” 5 (N.B. the numbering of the Psalm does not correspond to the traditional Douay-Rheims edition of the Bible, but adopts the Protestant version for “ecumenical” reasons).

He wanted it to be known that he was only speaking as a simple believer, Joseph Ratzinger, a Christian, to anyone who might wish to listen, adding that “everyone is free to disagree with me.” So, having eschewed the papal Tiara, he now laid aside his papal mitre. In this capacity, he dropped the following bombshell:

“The so-called institution account, that is, the words and gestures with which Jesus gave Himself to the disciples in bread and wine, forms the core of the tradition of the Lord’s Supper.” 6 [Emphasis added]

The formulation is undeniably Lutheran, being an expression of consubtantiation, which posits that Christ is substantially present with and in the bread and wine.7 In case of any doubt about the precise words that Ratzinger used, one can refer to the original German version which shows an exact correspondence with the correct English translation as given above.8

The formulation is undeniably Lutheran, being an expression of consubtantiation, which posits that Christ is substantially present with and in the bread and wine.7 In case of any doubt about the precise words that Ratzinger used, one can refer to the original German version which shows an exact correspondence with the correct English translation as given above.8

It is interesting to note that when the official translation was produced by the Vatican Secretariat of State, someone must have baulked at reproducing the heretical content of the original German version. So the italicized words were changed to “in the form of bread and wine.” This “improved” though still inadequate version may not sound as bad as the original, but, to do justice to Trent and Mysterium Fidei, the correct terminology is “under the appearances of bread and wine.”

Still, the theology behind the original version is of Lutheran inspiration, which has clearly influenced the creation of the Novus Ordo Mass. Some Catholic priests who have converted from Protestantism have been known to point out the similarities, to their dismay, as have many Lutherans, to their delight.

As for the ordinary faithful who attend the Novus Ordo Mass, the effects of discarding the correct terminology have been devastating for the continuity of the Faith. It has become second nature among so-called Eucharistic ministers charged with distributing Communion during Mass to discuss – and even squabble over – whose turn it is to “give out the bread” or “do the wine.” Some of the officially approved Communion hymns sung during the Novus Ordo Mass speak of “sharing bread and wine” and “Let us break bread together” and “drink wine together.”

Continued

Ratzinger’s objection to the “crystal clear” language of Scholasticism, coupled with his inveterate scorn for the “Manualist tradition,” suggests an intention (shared by all the neo-modernists) to detach himself not only from the form of Catholic theology, but also from its substance. That intention was deftly camouflaged in Pope John XXIII’s Opening Speech of the Council with his well-known platitude:

“The substance of the ancient doctrine of the deposit of faith is one thing, and the way in which it is presented, with the same meaning and judgment, is another.”

But if the substance of the Faith has no essential relation to the way it is presented, i.e., to the language in which it is expressed, as John XXIII’s aphorism seems to imply, we cannot even begin to talk about the “same meaning and judgment” because there would be no objective linguistic criteria with which to establish what is true or not true. We would simply lose the capacity to transmit with certainty the ontological truth about “being” (“what is”) – especially the Supreme Being (“I Am”, Exodus 3:14) – and its meaning.

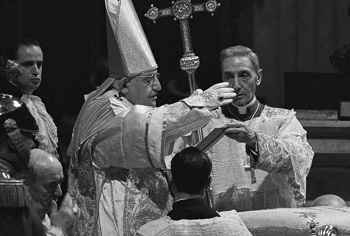

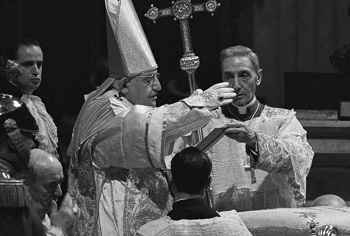

John XXIII opening Vatican II

It was common practice among progressivist theologians at the Council, including Fr. Ratzinger, to reject the original schemas which had been prepared by their conservative counterparts. In reformulating the language of the schema on the Constitution of the Church, for example, Ratzinger showed his determination not to keep to the same meaning as the original document:

“The new text describes the relationship between the Church and non-Catholic Christians without speaking of ‘membership.’ By shedding this terminological armour, the text acquired a much wider scope.” 1

As a theologian, Ratzinger shared much in common with his fellow neo-modernists of the Vatican II era in his aversion to the “fixed formulas” of Scholasticism on a whole range of substantial truths of Catholicism relating to the concept of “being.” These included the traditional teaching on the Real Presence, the nature of the Church as a monarchical institution, Revelation as definitively closed, the indissolubility of marriage and other defined dogmas which are unacceptable especially to Protestants. Ratzinger’s scepticism on all these issues is documented at various points throughout these articles.

Because of the seriousness of the subject, and the desire to be scrupulously accurate, we will take the original source of Ratzinger’s statements as written in the German versions, before they were somewhat laundered in later translations. The emphasis will be placed not on what he himself personally believed – this is difficult to ascertain because of the ambiguities and circumlocutions of his style – but on the content of his statements and how he presented them.

The Real Presence

Of all the areas of Catholic doctrine in which the absence of Scholastic thinking is most keenly felt, it must surely be the doctrine of the Real Presence. When Paul VI published his Encyclical Mysterium Fidei in 1965, he recognized that there was a crisis of belief in the Eucharist, especially in the Real Presence. He laid the blame in large part at the door of those who in spoken and written word “spread abroad opinions which disturb the faithful and fill their minds with no little confusion about matters of faith.” (§ 10)

he situation could not be more ironic: one of the theologians in question, a young academic named Fr. Joseph Ratzinger (who would eventually become one of Paul VI’s successors) was at that time busy spreading confusion about the Real Presence with subtle and convoluted theories. In 1966, Ratzinger wrote the following:

Paul VI made Ratzinger a Cardinal although he spread doubts on the Real Presence

"If one wanted to justify going to church by saying that one had to visit the God who is only present there, then this would in fact be a reason that made no sense, and would be rightly rejected by modern people.” 2

The whole passage raises a question which should never occur to a true Catholic: Is Christ really present in the tabernacle, or just thought by some to be there? In other words, is the Real Presence just a figment of some people’s imagination? These remarks, first published in 1966, inevitably caused a certain amount of scandal amongst the faithful, and there was a backlash of outraged criticism of their author. Nowadays, they are more likely to be greeted with shrug of indifference.

In response, Ratzinger tried to justify himself in a later publication, God is near us, by saying that there had been “a misapprehension” by his critics, and that his remarks do not deny the Real Presence or oppose adoration.3 However, in the normal understanding of his words, they certainly seemed to imply both.

Fr Faber, a champion & defender of the Real Presence

The 19th-century Oratorian priest, Fr. Frederick William Faber, for example, had no difficulty in accepting the presence of the “Eternal, Incomprehensible, Almighty Word who is everywhere and yet fixed there,” yet Who chooses to reside in “the quiet modesty of the Blessed Sacrament.” 4 It is not just modern man who rejects this teaching – the initial complaint (John 6:61) against it has been reiterated since Our Lord’s times: “This is intolerable language. Who could accept it?”

Transubstantiation is not a subject for ‘dialogue’

Pope Benedict XVI later reformulated the doctrine of transubstantiation in terms that not only eviscerated the Eucharist of its meaning but, on more than one occasion, strayed into the Protestant camp, if his words are to be judged according to the solemn definition of the Council of Trent.

During his tenure of the papal office, for instance, he wrote a trilogy on Jesus of Nazareth (reviewshere and here), making a point of publishing it under his own name; he explained the reason in the Preface to Volume 1: It was “in no way a magisterial act, but rather an expression of my personal search ‘for the face of the Lord.’ (Ps 27:8)” 5 (N.B. the numbering of the Psalm does not correspond to the traditional Douay-Rheims edition of the Bible, but adopts the Protestant version for “ecumenical” reasons).

He wanted it to be known that he was only speaking as a simple believer, Joseph Ratzinger, a Christian, to anyone who might wish to listen, adding that “everyone is free to disagree with me.” So, having eschewed the papal Tiara, he now laid aside his papal mitre. In this capacity, he dropped the following bombshell:

“The so-called institution account, that is, the words and gestures with which Jesus gave Himself to the disciples in bread and wine, forms the core of the tradition of the Lord’s Supper.” 6 [Emphasis added]

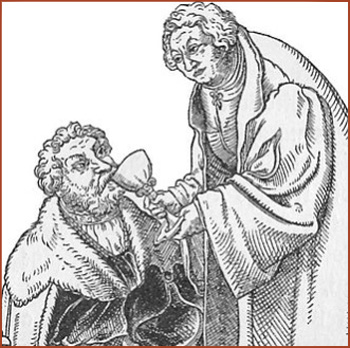

Ratzinger's notion of Eucharist is Lutheran - Above, Luther giving communion to John the Steadfast

It is interesting to note that when the official translation was produced by the Vatican Secretariat of State, someone must have baulked at reproducing the heretical content of the original German version. So the italicized words were changed to “in the form of bread and wine.” This “improved” though still inadequate version may not sound as bad as the original, but, to do justice to Trent and Mysterium Fidei, the correct terminology is “under the appearances of bread and wine.”

Still, the theology behind the original version is of Lutheran inspiration, which has clearly influenced the creation of the Novus Ordo Mass. Some Catholic priests who have converted from Protestantism have been known to point out the similarities, to their dismay, as have many Lutherans, to their delight.

As for the ordinary faithful who attend the Novus Ordo Mass, the effects of discarding the correct terminology have been devastating for the continuity of the Faith. It has become second nature among so-called Eucharistic ministers charged with distributing Communion during Mass to discuss – and even squabble over – whose turn it is to “give out the bread” or “do the wine.” Some of the officially approved Communion hymns sung during the Novus Ordo Mass speak of “sharing bread and wine” and “Let us break bread together” and “drink wine together.”

Continued

- Joseph Ratzinger, Theological Highlights of Vatican II, New York: Paulist Press, p. 66.

- J. Ratzinger, Die Sakramentale Begründung Christlicher Existenz (The Sacramental Foundation of Christian Existence), Kyrios: Freising-Meitingen, 1966, pp. 26-27.

- J. Ratzinger, God is Near Us: the Eucharist, the Heart of Life, San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2003, p. 91, Footnote 11.

- Frederick William Faber, The Blessed Sacrament, or, the works and ways of God, Baltimore: John Murphy Co., 1855, p. 125.

- J. Ratzinger/Benedict XVI, Jesus of Nazareth Part 1, From the Baptism in the Jordan to the Transfiguration, trans. Adrian Walker, New York and London: Doubleday, 2007, p. xxiii.

- J. Ratzinger, Jesus of Nazareth, Part 2, Holy Week: From the Entrance into Jerusalem to the Resurrection, trans. Philip Whitmore, San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2011, p. 115.

- According to the Lutheran Formula of Concord § 38, their concept of the real presence is understood to be “in pane, sub pane, cum pane”, (in the bread, under the bread, with the bread).

- J. Ratzinger, Jesus von Nazareth: Beiträge zur Christologie (Contributions to Christology), Part 2, Freiburg: Herder, 2008, p. 135: “Der sogenannte Einsetzungsbericht, das heißt die Worte und die Gesten, mit denen Jesus in Brot und Wein sich selbst den Jüngern gab, bildet den Kern der Abendmahls-Überlieferung.”

Posted October 16, 2024

______________________

______________________

Volume I |

Volume II |

Volume III |

Volume IV |

Volume V |

Volume VI |

Volume VII |

Volume VIII |

Volume IX |

Volume X |

Volume XI |

Special Edition |