What People are Commenting

New Fertilizers & Sacral Obscurity

Turning Bodies into Fertilizer

Hello TIA,

The Wall Street Journal published approvingly that the solution for cemeteries that are running out of space is to turn the dead ones in “compost”, which is the fashionable way to say fertilizer.

This is a “green” translation of a type of Pantheism, which preaches that after death we reincarnate into a tree or an animal. Buddhism and other pagan cults preach something like that.

How far we are from Catholic Civilization! Rather, we are under the dominium of Satan.

G.L.

This Tech Turns Loved Ones into Compost After Death

Conor Grant - Feb. 6, 2026

This is an edition of The Future of Everything newsletter, a look at how innovation and technology are transforming the way we live, work and play. If you’re not subscribed, sign up

here.

This is an edition of The Future of Everything newsletter, a look at how innovation and technology are transforming the way we live, work and play. If you’re not subscribed, sign up

here.

Like many burial grounds in the U.S., Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery is running out of room. But it may have found a solution: With the help of a German entrepreneur, cemetery officials believe they can profitably augment the property by turning the deceased into gardening soil.

This week, Tom Fairless reports on this eco-friendly alternative to burial and cremation.

________________________________________

The Future of Everything

A look at how innovation and technology are transforming the way we live, work and play.

Green-Wood plans to start its new program with around 18 composting vessels from Berlin-based startup, Meine Erde – which translates to “My Earth.”

The company uses a process called natural organic reduction, which uses the body’s own bacteria to transform human tissue. The dead are placed in sealed vessels bedded with clover, hay and straw and equipped to regulate airflow, temperature and moisture.

Then nature takes its course. Microbes break down everything but bones, which are ground into the final compost mix. Green-Wood’s plan is to use the nutrient-rich material to nurture trees, meadows and the bottom line.

In the U.S., 14 states have legalized human composting, starting with Washington in 2019. Parliaments from Germany to Switzerland, Belgium and the U.K. are considering it.

$5,000 - About how much, in U.S. dollars, Meine Erde charges for each coffin-like container, which it calls a cocoon – about twice the price of a simple cremation

The Wall Street Journal published approvingly that the solution for cemeteries that are running out of space is to turn the dead ones in “compost”, which is the fashionable way to say fertilizer.

This is a “green” translation of a type of Pantheism, which preaches that after death we reincarnate into a tree or an animal. Buddhism and other pagan cults preach something like that.

How far we are from Catholic Civilization! Rather, we are under the dominium of Satan.

G.L.

Conor Grant - Feb. 6, 2026

Marzena Skubatz for WSJ

Like many burial grounds in the U.S., Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery is running out of room. But it may have found a solution: With the help of a German entrepreneur, cemetery officials believe they can profitably augment the property by turning the deceased into gardening soil.

This week, Tom Fairless reports on this eco-friendly alternative to burial and cremation.

The Future of Everything

A look at how innovation and technology are transforming the way we live, work and play.

Green-Wood plans to start its new program with around 18 composting vessels from Berlin-based startup, Meine Erde – which translates to “My Earth.”

The company uses a process called natural organic reduction, which uses the body’s own bacteria to transform human tissue. The dead are placed in sealed vessels bedded with clover, hay and straw and equipped to regulate airflow, temperature and moisture.

Then nature takes its course. Microbes break down everything but bones, which are ground into the final compost mix. Green-Wood’s plan is to use the nutrient-rich material to nurture trees, meadows and the bottom line.

In the U.S., 14 states have legalized human composting, starting with Washington in 2019. Parliaments from Germany to Switzerland, Belgium and the U.K. are considering it.

$5,000 - About how much, in U.S. dollars, Meine Erde charges for each coffin-like container, which it calls a cocoon – about twice the price of a simple cremation

______________________

The Message of Sacral Obscurity

Dear TIA,

I thought that this was an interesting article that you may want to read or send to some one who may take interest in it.

In Maria,

R.L.

A Plea for Darkness in the Temple of God

Robert Keim

I often discuss aspects of medieval life that inform us, edify us, inspire us – but can’t really become a part of us, because too much has changed. The past is not always recoverable; some wounds never heal; cultural inertia surpasses the strength of the individual; and the contours of the mind, drawn from birth and hardened by long years of education and socialization, are not easily remade. A return to medieval life – or ancient life, or early modern life, or Victorian life – is impossible on multiple levels, and therefore undesirable, for to desire the impossible is to stray, dangerously, from the goodness and glory of the Real.

But this essay is different. This essay is about something that can be done, and done easily, and done today. No nostalgia, no radical commitment to tradition, no papal dispensation is required. In the worst case, some electrical work might be needed. In the best case, all it takes is someone with the authority, and the willingness, to flip a few switches from on to off.

The Dark Ages – that’s the outmoded name for the Middle Ages, or for the first half of the Middle Ages. It’s not taken too seriously anymore. The Oxford English Dictionary explains:

The term Dark Ages was commonly used by 19th-century historians. However, as knowledge of the history and culture of the period increased, the negative connotations of the term began to be questioned; it is now more commonly used in popular rather than technical discourse. The term is now also frequently reconceptualized, as referring to a period for which historical evidence is relatively scant.

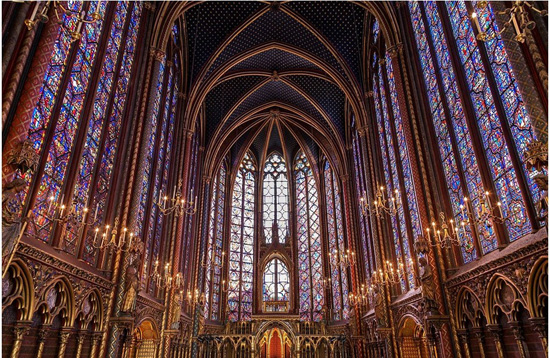

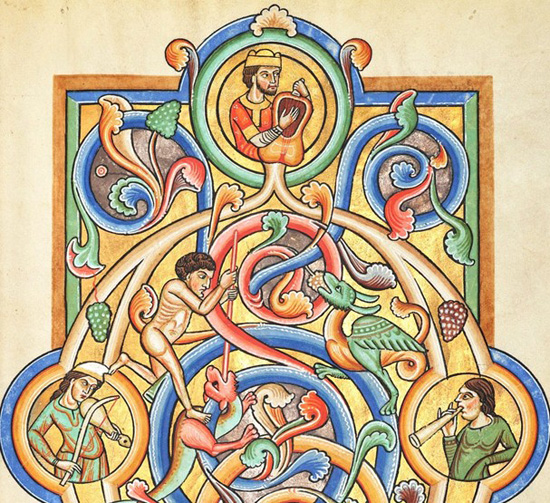

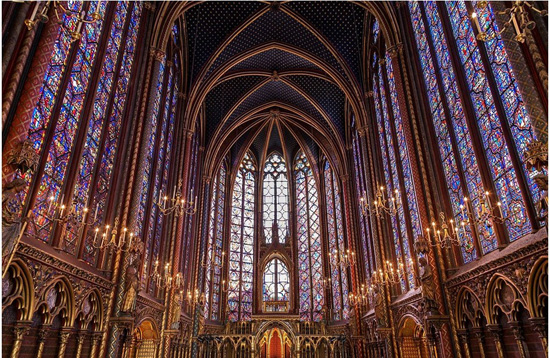

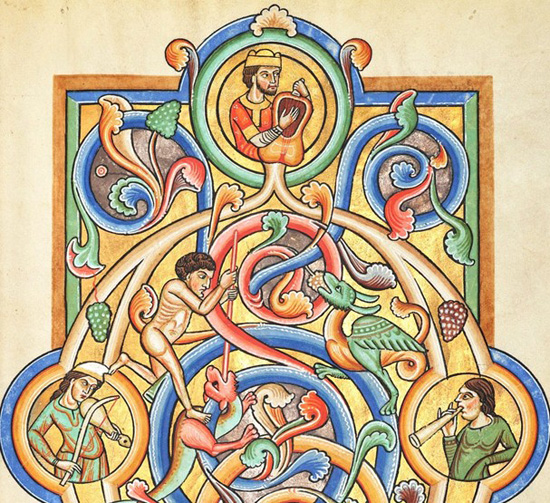

It was a judgmental, derogatory label for an era that produced the sort of darkness you see here:

And here:

And here:

But as some of you know, I like the term, because I like darkness, if we have it when and where it ought to be. I like darkness at night, when I want to see the stars, not the wall-sized television glowing in my neighbor’s “living” room. I like darkness in the evening, when I’m reading to my children, and hoping that for a little while they will see less, and imagine more. And I like darkness in church, when my principal objective is prayer, and when the person I most want to see is illuminated by candles, and when the God whom I am there to seek is already perfect Light unto my soul.

The sun shined as brightly in medieval Europe as it does today – maybe more so, given the lack of air pollution and skyscrapers. There were bright flowers, windows, vibrant works of art, and eyes made especially sensitive by long years of natural lighting. My understanding is that centuries after the end of the medieval period, rural folks still could work outside during the night, and quite comfortably, as long as they had enough moonlight. So medieval civilization as a whole wasn’t particularly dark in a literal sense. Nor was it particularly dark in a figurative sense, except insofar as every human society is to some degree blackened and overshadowed by sin.

However, the Middle Ages was a time of “liturgical darkness.” Dr. Geoffrey Hull, in his extraordinary book The Banished Heart, mentions the shift in lighting as part of the transition from medieval to modern liturgical aesthetics.

While the baroque and rococo periods were not without liturgical growth…, so much aping of worldly court ceremonial inevitably led to the secularizing not of the structure of the liturgy…, but of its performance. One has only to listen to a Mass by Mozart or Haydn to realize how little different church music of this era must have sounded from that of the concert hall. All kinds of secular instruments were now being used in church, while the organ itself was played in a bombastic manner that drowned out the singing of the liturgical texts. The ceremonial, too, tended to be stiff, gaudy and exhibitionistic, those in the sanctuary often looking and acting more like obsequious courtiers than recollected sacred ministers.

That passage gives you an idea of the era’s general attitude toward the liturgical experience. What he describes may not sound so bad compared to the liturgical desolation that many people endure today, but we must also be sensitive to the underlying principles of such developments, and how these principles might gradually conduce to changes of a far more drastic and lamentable nature.

Hull continues:

As for the churches themselves, their appearance was inevitably affected by this new orientation. The typical baroque church was built to resemble a theatre or a concert hall in plan and decoration…. Pews and seats for the pious spectators of liturgical performances appeared everywhere, and the choir moved from the recess between the sanctuary and the nave to the organ loft at the back of the church. In baroque temples the atmosphere of sacred darkness and “dim religious light” from stained glass windows and candles gave way to the hard brightness of whitewashed walls and huge chandeliers.

If whitewashed walls and an overgenerous supply of candles can produce “hard brightness,” how would we describe the illumination of our own churches, where a veritable cannonade of electric light is somehow integral to the process of preparing a building, and its occupants, for divine worship?

Continue reading here

I thought that this was an interesting article that you may want to read or send to some one who may take interest in it.

In Maria,

R.L.

Robert Keim

I often discuss aspects of medieval life that inform us, edify us, inspire us – but can’t really become a part of us, because too much has changed. The past is not always recoverable; some wounds never heal; cultural inertia surpasses the strength of the individual; and the contours of the mind, drawn from birth and hardened by long years of education and socialization, are not easily remade. A return to medieval life – or ancient life, or early modern life, or Victorian life – is impossible on multiple levels, and therefore undesirable, for to desire the impossible is to stray, dangerously, from the goodness and glory of the Real.

But this essay is different. This essay is about something that can be done, and done easily, and done today. No nostalgia, no radical commitment to tradition, no papal dispensation is required. In the worst case, some electrical work might be needed. In the best case, all it takes is someone with the authority, and the willingness, to flip a few switches from on to off.

The Dark Ages – that’s the outmoded name for the Middle Ages, or for the first half of the Middle Ages. It’s not taken too seriously anymore. The Oxford English Dictionary explains:

The term Dark Ages was commonly used by 19th-century historians. However, as knowledge of the history and culture of the period increased, the negative connotations of the term began to be questioned; it is now more commonly used in popular rather than technical discourse. The term is now also frequently reconceptualized, as referring to a period for which historical evidence is relatively scant.

It was a judgmental, derogatory label for an era that produced the sort of darkness you see here:

And here:

And here:

But as some of you know, I like the term, because I like darkness, if we have it when and where it ought to be. I like darkness at night, when I want to see the stars, not the wall-sized television glowing in my neighbor’s “living” room. I like darkness in the evening, when I’m reading to my children, and hoping that for a little while they will see less, and imagine more. And I like darkness in church, when my principal objective is prayer, and when the person I most want to see is illuminated by candles, and when the God whom I am there to seek is already perfect Light unto my soul.

The sun shined as brightly in medieval Europe as it does today – maybe more so, given the lack of air pollution and skyscrapers. There were bright flowers, windows, vibrant works of art, and eyes made especially sensitive by long years of natural lighting. My understanding is that centuries after the end of the medieval period, rural folks still could work outside during the night, and quite comfortably, as long as they had enough moonlight. So medieval civilization as a whole wasn’t particularly dark in a literal sense. Nor was it particularly dark in a figurative sense, except insofar as every human society is to some degree blackened and overshadowed by sin.

However, the Middle Ages was a time of “liturgical darkness.” Dr. Geoffrey Hull, in his extraordinary book The Banished Heart, mentions the shift in lighting as part of the transition from medieval to modern liturgical aesthetics.

While the baroque and rococo periods were not without liturgical growth…, so much aping of worldly court ceremonial inevitably led to the secularizing not of the structure of the liturgy…, but of its performance. One has only to listen to a Mass by Mozart or Haydn to realize how little different church music of this era must have sounded from that of the concert hall. All kinds of secular instruments were now being used in church, while the organ itself was played in a bombastic manner that drowned out the singing of the liturgical texts. The ceremonial, too, tended to be stiff, gaudy and exhibitionistic, those in the sanctuary often looking and acting more like obsequious courtiers than recollected sacred ministers.

That passage gives you an idea of the era’s general attitude toward the liturgical experience. What he describes may not sound so bad compared to the liturgical desolation that many people endure today, but we must also be sensitive to the underlying principles of such developments, and how these principles might gradually conduce to changes of a far more drastic and lamentable nature.

Hull continues:

As for the churches themselves, their appearance was inevitably affected by this new orientation. The typical baroque church was built to resemble a theatre or a concert hall in plan and decoration…. Pews and seats for the pious spectators of liturgical performances appeared everywhere, and the choir moved from the recess between the sanctuary and the nave to the organ loft at the back of the church. In baroque temples the atmosphere of sacred darkness and “dim religious light” from stained glass windows and candles gave way to the hard brightness of whitewashed walls and huge chandeliers.

If whitewashed walls and an overgenerous supply of candles can produce “hard brightness,” how would we describe the illumination of our own churches, where a veritable cannonade of electric light is somehow integral to the process of preparing a building, and its occupants, for divine worship?

Continue reading here

Posted February 17, 2026

______________________

The opinions expressed in this section - What People Are Commenting - do not necessarily express those of TIA

______________________

______________________

The man who never goes to a grocery store (Trump) tells us that the prices of groceries are going down rapidly.

We who go to the store find the opposite - price of coffee has jumped nearly 20%, ground beef is up 15.5% and fresh fruit and vegetables are up more than 11%. In fact, grocery prices are sitting nearly 26% higher than they were five years ago.

H.T.