Traditionalist Issues

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dialogue Mass - CXLVI

‘The Holy Office Was Destroyed by Ratzinger’

In this article, we will continue with the intervention of Card. Frings at the Council on the subject of Revelation, and then move on to what he – or rather Fr. Ratzinger speaking through him – had to say on a number of other topics.

On 14 November 1962, Card. Frings, using Ratzinger’s words, gave a non placet vote to the original schema on the Sources of Revelation, on the grounds that “by these two sources [Scripture and Tradition] our separated brethren will be offended, a new gap will be created.”

Here we see the intention that would prevail at the Council: to retreat from the duty to proclaim the teachings of the Church in their fullness for fear of upsetting those outside the Faith who have already rejected them. But a deliberate and indefinite silence on these doctrines is tantamount to their denial in practice.

The repercussions of Ratzinger’s intervention for the future of Catholic theology can hardly be exaggerated. In his final interview with Peter Seewald, Pope Benedict stated that the rejection of the original draft on Revelation was “a real turning point” in the Council.1

The repercussions of Ratzinger’s intervention for the future of Catholic theology can hardly be exaggerated. In his final interview with Peter Seewald, Pope Benedict stated that the rejection of the original draft on Revelation was “a real turning point” in the Council.1

After some vicissitudes, the new schema, based on his theology with input from Henri de Lubac, Karl Rahner and Yves Congar, became Vatican II’s Dei Verbum. As a result of the “New Theology,” the concept of an objective, fixed and immutable Revelation, supernatural in nature and existing independently without the aid of man’s input, has vanished from the curriculum of all educational establishments, including seminaries, except those dedicated to maintaining Catholic Tradition.

It was eclipsed by the overwhelmingly greater emphasis placed on Scripture seen as something of an Elder Statesman, leaving Tradition as the poor relation having nothing of extra value to offer. Furthermore, the biblical events were seen as “signs” of God’s Revelation interpreted through the experience of the people – as if they were the Apostles who had known, seen and heard Our Lord from first-hand witness.

The Council Fathers were persuaded to accept the final draft of Dei Verbum by means of the blandishments and double-speak contained in the document. It solemnly assured them from the outset that it was “following in the footsteps of the Council of Trent and of the First Vatican Council” and that it aimed “to set forth authentic doctrine on divine revelation and how it is handed on.” But it did not match those Councils in purity of doctrine or precision of expression.

When, for example, it stated that “the way of interpreting Scripture is subject finally to the judgment of the Church,” not everyone would have realized the intentional ambiguity in the word Church. In the Vatican I document, by the principle of antonomasia, it meant the Hierarchy. But in Vatican II, it was a metonym for all the “People of God” collectively sharing in the teaching authority of the Church. Thus, the task of interpreting Scripture is seen as the responsibility of all – a position that accords exactly with Protestantism. The appeal to Vatican I can be seen for what it is ‒ an exercise in sophistry.

Let us not underestimate the significance of this “turning point” for the future of the Church. Now, over five decades later, we can see how the “new Revelation” has been gradually taking shape in the Protestantization of the Church’s Constitution, Liturgy and Laws, culminating in the Synodal Way of Pope Francis which is in the process of trying to change the very essence of the Church permanently.

The Ratzinger-Frings attack on the Holy Office (1963)

On 8 November 1963, Card. Frings declared in the Conciliar aula: “The Holy Office’s manner of conducting itself in many spheres is not in step with our times, is detrimental to the Church, and is a cause of scandal for many.”

He was, of course, speaking from a script known to have been previously dictated by Ratzinger.2 Peter Seewald commented that “no one had ever dared before to criticize Ottaviani’s machinery so fiercely.” 3 It is a well recorded fact in the annals of the Council that Card. Ottaviani was several times publicly humiliated by progressivist reformers, especially from Germany, in a manner that defied both Christian charity and the gentlemanly code of ethics. The Frings/Ratzinger broadside, which constituted one of the Council’s most emotionally-charged and dramatic events, was no exception.

There was an underlying point to this savage denunciation of the Holy Office and the humiliation of its Secretary, Card. Ottaviani, which may not be apparent at first sight, and stands in need of some explanation. As long as the Holy Office stood as an impregnable bastion of Catholic Truth yet-to-be-razed, Ratzinger’s theory of Revelation would have no chance of being approved by the Church’s Magisterium. Nor, moreover, would such notions as the “inverted pyramid,” disrespect for the Ecclesia Docens, “active participation” of the laity, “ecumenism” and the “Synod of Synodality” have stood a chance of succeeding without Ratzinger’s redefinition of Divine Revelation.

There was an underlying point to this savage denunciation of the Holy Office and the humiliation of its Secretary, Card. Ottaviani, which may not be apparent at first sight, and stands in need of some explanation. As long as the Holy Office stood as an impregnable bastion of Catholic Truth yet-to-be-razed, Ratzinger’s theory of Revelation would have no chance of being approved by the Church’s Magisterium. Nor, moreover, would such notions as the “inverted pyramid,” disrespect for the Ecclesia Docens, “active participation” of the laity, “ecumenism” and the “Synod of Synodality” have stood a chance of succeeding without Ratzinger’s redefinition of Divine Revelation.

According to the teaching of St. Thomas Aquinas, Revelation is indissolubly linked to the authoritative oral Tradition vested in the Magisterium, whose duty it is to pass on the Faith taught by Our Lord to the Apostles. But it was precisely this Tradition that was irksome to Ratzinger because it was an obstacle to the fabled “unity” with Protestants who rejected it in favor of Scripture Alone. His opposition to Ottaviani was expressed in his statement that the Council should “be less dominated by the current Magisterium” and “give greater place to Scripture and the Fathers.” 4 It was another way of saying that he favored Scripture over Tradition.

Ratzinger had already crossed swords with Ottaviani on a previous occasion when he counteracted a decision of the Holy Office regarding a book published by a former doctoral student of his which proposed a Protestant-friendly reform of the Church. The author, Fr. Heinz Schütte, came to him in 1960 to complain that he had received a Monitum requiring him to correct certain errors in his book, On Reunification in Faith,5 and had his permission to teach withdrawn.

In contradiction to Ottaviani’s intervention, Ratzinger congratulated the author by saying that he regarded the book as “a true ecumenical signal that spread light wide and awakened Gospel hope, especially among our Evangelical brothers.” 6 Benedict later chose him to be his close collaborator in preparing the Joint Declaration on Justification with the Lutherans.

This small digression illuminates a key factor in Ratzinger’s thought. The Schütte affair demonstrates that, even before the Council opened, he was imbued with a spirit of opposition to Ottaviani and his work. It is understandable, therefore, that he would be determined to change the nature of the Holy Office. Henri de Lubac (who had himself been investigated by the Holy Office prior to the removal from his duties at the Lyon University) commented pointedly:

“It is not exaggerating to say that on that day [8 November 1963] the old Holy Office, in the way it conducted its procedures, was destroyed by Ratzinger in collaboration with his archbishop.” 7

In fact, Ratzinger held de Lubac in the highest regard, and collaborated with those who had been censored or at least held in suspicion by the Holy Office, such as Yves Congar, Karl Rahner and Teilhard de Chardin. So there is plenty of evidence to show that he had a dog in this fight against the Holy Office, and displayed a similar anti-Roman spirit to that of the proponents of the “New Theology.” After Paul VI reformed the Holy Office at Frings’s (and Ratzinger’s) behest and turned it into a shadow of its former self – the much milder and ineffective Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith – Ratzinger became its Prefect in 1981.

In fact, Ratzinger held de Lubac in the highest regard, and collaborated with those who had been censored or at least held in suspicion by the Holy Office, such as Yves Congar, Karl Rahner and Teilhard de Chardin. So there is plenty of evidence to show that he had a dog in this fight against the Holy Office, and displayed a similar anti-Roman spirit to that of the proponents of the “New Theology.” After Paul VI reformed the Holy Office at Frings’s (and Ratzinger’s) behest and turned it into a shadow of its former self – the much milder and ineffective Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith – Ratzinger became its Prefect in 1981.

It is undeniable that all manner of heresies proliferated throughout the Church and were allowed to continue unchecked under his watch, beset as he was by the problems that he himself had helped bring into being at Vatican II.

These included a decline in papal authority and an accompanying rise in episcopal independence, a condoning of religious liberty, freedom of conscience and unrestricted theological pluralism, contempt for Scholastic precision and logic, and a general turning away from dogmatic truth. Having accepted Vatican II’s Collegiality, his hands were tied in dealing with powerful Bishops’ Conferences, especially those of Germany and France. Romano Amerio has documented examples of Ratzinger’s inability to overcome these post-Conciliar obstacles.8

Continued

On 14 November 1962, Card. Frings, using Ratzinger’s words, gave a non placet vote to the original schema on the Sources of Revelation, on the grounds that “by these two sources [Scripture and Tradition] our separated brethren will be offended, a new gap will be created.”

Here we see the intention that would prevail at the Council: to retreat from the duty to proclaim the teachings of the Church in their fullness for fear of upsetting those outside the Faith who have already rejected them. But a deliberate and indefinite silence on these doctrines is tantamount to their denial in practice.

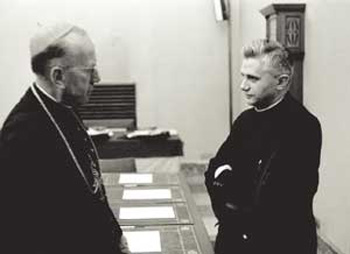

Journalist Peter Seewald poses with Pope Ratzinger at the release of their book Benedict XVI: A Life

After some vicissitudes, the new schema, based on his theology with input from Henri de Lubac, Karl Rahner and Yves Congar, became Vatican II’s Dei Verbum. As a result of the “New Theology,” the concept of an objective, fixed and immutable Revelation, supernatural in nature and existing independently without the aid of man’s input, has vanished from the curriculum of all educational establishments, including seminaries, except those dedicated to maintaining Catholic Tradition.

It was eclipsed by the overwhelmingly greater emphasis placed on Scripture seen as something of an Elder Statesman, leaving Tradition as the poor relation having nothing of extra value to offer. Furthermore, the biblical events were seen as “signs” of God’s Revelation interpreted through the experience of the people – as if they were the Apostles who had known, seen and heard Our Lord from first-hand witness.

The Council Fathers were persuaded to accept the final draft of Dei Verbum by means of the blandishments and double-speak contained in the document. It solemnly assured them from the outset that it was “following in the footsteps of the Council of Trent and of the First Vatican Council” and that it aimed “to set forth authentic doctrine on divine revelation and how it is handed on.” But it did not match those Councils in purity of doctrine or precision of expression.

When, for example, it stated that “the way of interpreting Scripture is subject finally to the judgment of the Church,” not everyone would have realized the intentional ambiguity in the word Church. In the Vatican I document, by the principle of antonomasia, it meant the Hierarchy. But in Vatican II, it was a metonym for all the “People of God” collectively sharing in the teaching authority of the Church. Thus, the task of interpreting Scripture is seen as the responsibility of all – a position that accords exactly with Protestantism. The appeal to Vatican I can be seen for what it is ‒ an exercise in sophistry.

Let us not underestimate the significance of this “turning point” for the future of the Church. Now, over five decades later, we can see how the “new Revelation” has been gradually taking shape in the Protestantization of the Church’s Constitution, Liturgy and Laws, culminating in the Synodal Way of Pope Francis which is in the process of trying to change the very essence of the Church permanently.

The Ratzinger-Frings attack on the Holy Office (1963)

On 8 November 1963, Card. Frings declared in the Conciliar aula: “The Holy Office’s manner of conducting itself in many spheres is not in step with our times, is detrimental to the Church, and is a cause of scandal for many.”

He was, of course, speaking from a script known to have been previously dictated by Ratzinger.2 Peter Seewald commented that “no one had ever dared before to criticize Ottaviani’s machinery so fiercely.” 3 It is a well recorded fact in the annals of the Council that Card. Ottaviani was several times publicly humiliated by progressivist reformers, especially from Germany, in a manner that defied both Christian charity and the gentlemanly code of ethics. The Frings/Ratzinger broadside, which constituted one of the Council’s most emotionally-charged and dramatic events, was no exception.

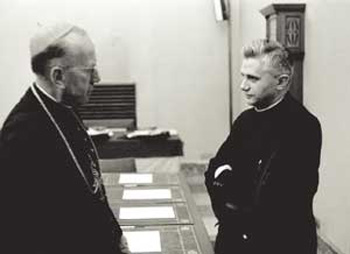

A young Fr. Ratzinger, secretary of Card. Frings at the Council

According to the teaching of St. Thomas Aquinas, Revelation is indissolubly linked to the authoritative oral Tradition vested in the Magisterium, whose duty it is to pass on the Faith taught by Our Lord to the Apostles. But it was precisely this Tradition that was irksome to Ratzinger because it was an obstacle to the fabled “unity” with Protestants who rejected it in favor of Scripture Alone. His opposition to Ottaviani was expressed in his statement that the Council should “be less dominated by the current Magisterium” and “give greater place to Scripture and the Fathers.” 4 It was another way of saying that he favored Scripture over Tradition.

Ratzinger had already crossed swords with Ottaviani on a previous occasion when he counteracted a decision of the Holy Office regarding a book published by a former doctoral student of his which proposed a Protestant-friendly reform of the Church. The author, Fr. Heinz Schütte, came to him in 1960 to complain that he had received a Monitum requiring him to correct certain errors in his book, On Reunification in Faith,5 and had his permission to teach withdrawn.

In contradiction to Ottaviani’s intervention, Ratzinger congratulated the author by saying that he regarded the book as “a true ecumenical signal that spread light wide and awakened Gospel hope, especially among our Evangelical brothers.” 6 Benedict later chose him to be his close collaborator in preparing the Joint Declaration on Justification with the Lutherans.

This small digression illuminates a key factor in Ratzinger’s thought. The Schütte affair demonstrates that, even before the Council opened, he was imbued with a spirit of opposition to Ottaviani and his work. It is understandable, therefore, that he would be determined to change the nature of the Holy Office. Henri de Lubac (who had himself been investigated by the Holy Office prior to the removal from his duties at the Lyon University) commented pointedly:

“It is not exaggerating to say that on that day [8 November 1963] the old Holy Office, in the way it conducted its procedures, was destroyed by Ratzinger in collaboration with his archbishop.” 7

Ratzinger was chosen for the Holy Office because he knew the way to destroy it

It is undeniable that all manner of heresies proliferated throughout the Church and were allowed to continue unchecked under his watch, beset as he was by the problems that he himself had helped bring into being at Vatican II.

These included a decline in papal authority and an accompanying rise in episcopal independence, a condoning of religious liberty, freedom of conscience and unrestricted theological pluralism, contempt for Scholastic precision and logic, and a general turning away from dogmatic truth. Having accepted Vatican II’s Collegiality, his hands were tied in dealing with powerful Bishops’ Conferences, especially those of Germany and France. Romano Amerio has documented examples of Ratzinger’s inability to overcome these post-Conciliar obstacles.8

Continued

- Benedict XVI with Peter Seewald, Last Testament: In His Own Words, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2016, p. 134.

- Norbert Trippen, Josef Kardinal Frings (1887-1978): Sein Wirken Für Die Weltkirche Und Seine Letzten Bischofsjahre (His Work for the Universal Church and his Final Episcopal Years), 2 volumes, vol. 2, Paderborn: Ferdinand Schöningh, 2005, p. 383.

- Peter Seewald, Benedict XVI: A Life. Volume One: Youth in Nazi Germany to the Second Vatican Council 1927–1965, trans. Dinah Livingstone, London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2020, p. 444.

- Benedict XVI, Last Testament, p. 131.

- Heinz Schütte, Um die Wiedervereinigung im Glauben (On Reunification in Faith), Essen: Fredebeul & Koenen, 1958.

- P. Seewald, op, cit., pp. 430-431.

- Henri de Lubac, Entretien autour de Vatican II: Souvenirs et Réflexions (A Discussion about Vatican II: Memories and Thoughts), Paris: Cerf, 1985, p. 123.

- Romano Amerio, Iota Unum: A Study of Changes in the Catholic Church in the Twentieth Century, Angelus Press, 1996, pp. 151-152.

Posted February 3, 2025

______________________

______________________

Volume I |

Volume II |

Volume III |

Volume IV |

Volume V |

Volume VI |

Volume VII |

Volume VIII |

Volume IX |

Volume X |

Volume XI |

Special Edition |