Traditionalist Issues

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dialogue Mass - CLVIII

The Sillon & the Mysticism of Democracy

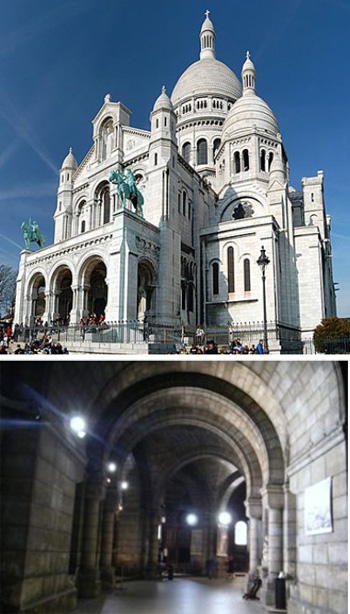

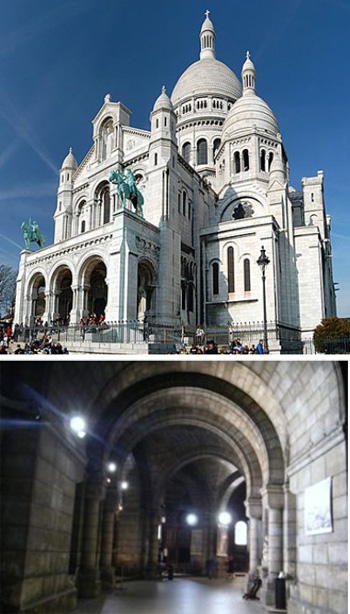

A contemporary witness, N. Ariès, who had personal knowledge of the Sillon, wrote an extremely detailed chronicle of its constitution, aims and activities from its inception to its suppression by Pope Pius X in 1910. From this first-hand source it emerges that a total commitment was demanded of the Young Guards to the cause of Democracy. A type of Chivalry Order turned to impose Democracy. Under Sangnier’s spiritual direction, they underwent a ceremony called a “veillée d’armes,” vigil of arms 1 – the first of which was, by his own account, held on December 20, 1901, in the crypt of the Sacré-Cœur, Paris.

Kneeling at the altar, the new recruits had to make a vow to dedicate their lives totally to the Sillon and the cause of Democracy. 2 Henry du Roure, who was perhaps the closest of Marc Sangier’s lieutenants, stated that the homage was made to Sangnier himself as the suzerain of the new knights: They felt “the necessity to believe in Marc’s providential vision and vow to him an absolute and unconditional confidence.” 3

Kneeling at the altar, the new recruits had to make a vow to dedicate their lives totally to the Sillon and the cause of Democracy. 2 Henry du Roure, who was perhaps the closest of Marc Sangier’s lieutenants, stated that the homage was made to Sangnier himself as the suzerain of the new knights: They felt “the necessity to believe in Marc’s providential vision and vow to him an absolute and unconditional confidence.” 3

According to Msgr. Eugène Beaupin, former chaplain to the Young Guard, the prayer formula accompanying the homage was composed by Sangnier himself. 4 It was not, however, a prayer of faith, but of presumption. It was subtly worded to convey the assurance that God has to grant a successful outcome for the Young Guards because they are “good soldiers of Christ” and because their plans to “democratize” the Church would be certain to make God’s Kingdom come on earth.

We also know from the words of Louis Cousin, who was privy to the early formation of the Young Guards in Stanislas College, that they referred to their work for Democracy as a “Sacred Cause” for which they were exhorted to give their whole lives even to the point of death, with the promise of immortality. 5 At this point, a dizzy spirit entered the proceedings, which influenced the young men to reject hierarchical control as “paternalism,” and stoked the fires of independence and self-sufficiency.

Ariès observed that, from the moment they joined the Sillon, the personality of the Young Guards underwent a change with an obsession – “idée fixe” – about their role as promoters of Democracy. They dedicated themselves to a high-demand schedule of activities which was designed to prevent them from spending time alone or from thinking for themselves. This constant round of activities included distributing the Sillon’s newspaper regularly and unfailingly at church doors, attending study circles, organizing endless meetings and local congresses, putting up posters, running a committee for propaganda and an office for social work, and generally maintaining the “spirit of the Sillon.”

As their leader, Sangnier accepted the adulation of his committed followers while requiring their total acceptance of his modernist ideology. It was Sangnier’s wish that they should have as their watchword Conscience and Responsibility – words susceptible of infinite malleability.

This new Chivalry Order became an efficient tool to achieve Sangnier’s project. He indoctrinated the militant young conscripts into believing that they had been “called” to a “vocation” to fight the good fight; and their responsibility was to carry out his orders to the letter.

But the combat was to promote modern, progressivist values – Democracy, freedom and equality – inside the Church. It was not long before the Sillon’s exclusive orientation for Democracy became identified with the Catholic Faith.

But the combat was to promote modern, progressivist values – Democracy, freedom and equality – inside the Church. It was not long before the Sillon’s exclusive orientation for Democracy became identified with the Catholic Faith.

Another important testimony, this time from a member of the Sillon, gives an insider’s view of the organization. The journalist and social commentator, Joseph Folliet, pointed out that, as a result of what he called this “confusionnisme politico-religieux” [political-religious confusion], no one – including the Sillonists themselves – could be sure whether the Sillon was a “religious movement with social and political tendencies or a political movement of religious inspiration.” 6 Either way, the credibility of the Church as an organization of supernatural origin would be compromised.

In this connection, Folliet’s insightful analysis sheds light on the fundamental reason why Pius X eventually suppressed the Sillon, and is worth quoting at some length, in translation:

“The danger of confusion was that it would produce a sort of humanitarian naturalism which would eventually place Christ and the Church at the service of Democracy, that is to say, it would end up subordinating the spiritual to the temporal…

“At the root of this confusion and danger lie, we believe, the anti-intellectualism of the Sillon, its disdain for precise explanations and definitions, its refusal to accept doctrines with sharply defined edges, which have been too firmly expressed. ‘Go wherever life takes you’ is a good formula, but can be understood in two opposing ways; we must also strive to live life, which cannot be done without a minimum of intellectual clarity and logical reasoning. The Sillonist Movement was somewhat lacking [doctrinally] in backbone – a deficiency all the more damaging because it was a movement for young people, some of them very young, ardent, active, enthusiastic, inclined to give free rein to their emotions… Their imprecision of thought was to lead them, if not into error, at least into doctrinal muddle.” 7

“At the root of this confusion and danger lie, we believe, the anti-intellectualism of the Sillon, its disdain for precise explanations and definitions, its refusal to accept doctrines with sharply defined edges, which have been too firmly expressed. ‘Go wherever life takes you’ is a good formula, but can be understood in two opposing ways; we must also strive to live life, which cannot be done without a minimum of intellectual clarity and logical reasoning. The Sillonist Movement was somewhat lacking [doctrinally] in backbone – a deficiency all the more damaging because it was a movement for young people, some of them very young, ardent, active, enthusiastic, inclined to give free rein to their emotions… Their imprecision of thought was to lead them, if not into error, at least into doctrinal muddle.” 7

Folliet’s assessment was correct, but did not go far enough. It is true that the Sillonists had no interest in promoting objectivity and truth, but describing them as doctrinally confused is an understatement. There were, in fact, some members of the clergy, priests and Bishops in various parts of France, who accused them of positively promoting doctrinal error and also leading many young souls astray.

Nor had they any intention of obeying the Bishops. When, for instance, the Bishop of Quimper prohibited his priests from having anything to do with the Sillon, Marc Sagnier retorted that they should take no notice of his order and added: “I may be accused of being an anarchist, but I don’t care a hoot about that.” 8

To be continued

The Sacred Heart Basilica in Paris & its crypt where the Sillon members paid their homage to Sangnier

According to Msgr. Eugène Beaupin, former chaplain to the Young Guard, the prayer formula accompanying the homage was composed by Sangnier himself. 4 It was not, however, a prayer of faith, but of presumption. It was subtly worded to convey the assurance that God has to grant a successful outcome for the Young Guards because they are “good soldiers of Christ” and because their plans to “democratize” the Church would be certain to make God’s Kingdom come on earth.

We also know from the words of Louis Cousin, who was privy to the early formation of the Young Guards in Stanislas College, that they referred to their work for Democracy as a “Sacred Cause” for which they were exhorted to give their whole lives even to the point of death, with the promise of immortality. 5 At this point, a dizzy spirit entered the proceedings, which influenced the young men to reject hierarchical control as “paternalism,” and stoked the fires of independence and self-sufficiency.

Ariès observed that, from the moment they joined the Sillon, the personality of the Young Guards underwent a change with an obsession – “idée fixe” – about their role as promoters of Democracy. They dedicated themselves to a high-demand schedule of activities which was designed to prevent them from spending time alone or from thinking for themselves. This constant round of activities included distributing the Sillon’s newspaper regularly and unfailingly at church doors, attending study circles, organizing endless meetings and local congresses, putting up posters, running a committee for propaganda and an office for social work, and generally maintaining the “spirit of the Sillon.”

As their leader, Sangnier accepted the adulation of his committed followers while requiring their total acceptance of his modernist ideology. It was Sangnier’s wish that they should have as their watchword Conscience and Responsibility – words susceptible of infinite malleability.

This new Chivalry Order became an efficient tool to achieve Sangnier’s project. He indoctrinated the militant young conscripts into believing that they had been “called” to a “vocation” to fight the good fight; and their responsibility was to carry out his orders to the letter.

A meeting at the Sillon’s headquarters

Another important testimony, this time from a member of the Sillon, gives an insider’s view of the organization. The journalist and social commentator, Joseph Folliet, pointed out that, as a result of what he called this “confusionnisme politico-religieux” [political-religious confusion], no one – including the Sillonists themselves – could be sure whether the Sillon was a “religious movement with social and political tendencies or a political movement of religious inspiration.” 6 Either way, the credibility of the Church as an organization of supernatural origin would be compromised.

In this connection, Folliet’s insightful analysis sheds light on the fundamental reason why Pius X eventually suppressed the Sillon, and is worth quoting at some length, in translation:

“The danger of confusion was that it would produce a sort of humanitarian naturalism which would eventually place Christ and the Church at the service of Democracy, that is to say, it would end up subordinating the spiritual to the temporal…

Marc Sagnier delivering a speech

Folliet’s assessment was correct, but did not go far enough. It is true that the Sillonists had no interest in promoting objectivity and truth, but describing them as doctrinally confused is an understatement. There were, in fact, some members of the clergy, priests and Bishops in various parts of France, who accused them of positively promoting doctrinal error and also leading many young souls astray.

Nor had they any intention of obeying the Bishops. When, for instance, the Bishop of Quimper prohibited his priests from having anything to do with the Sillon, Marc Sagnier retorted that they should take no notice of his order and added: “I may be accused of being an anarchist, but I don’t care a hoot about that.” 8

To be continued

- The ceremony of the veillée d’armes, originating from medieval chivalric orders, was a significant step towards knighthood. Before receiving the accolade, the knight-to-be underwent an all-night vigil of meditation and prayer to ensure his readiness for battle.

- N. Ariès, “Le Sillon” et le Mouvement Démocratique, Paris: Nouvelle Librairie Nationale, 1910, p. 226 .

- Hughes Petit, L’Eglise, le Sillon, et l’Action Française, Paris: Nouvelles Édtions Latines, 1998, p. 17.

- Eugène Beaupin, "La vie religieuse au Sillon" (Religious life in the Sillon), Chronique Sociale de France, vol. 60, No. 2, March-April 1950, p. 77.

- L. Cousin, op. cit., p, 26.

- Joseph Folliet, "Essai de jugement équitable sur le Sillon" (A fair-minded judgement of the Sillon), ibid., p. 126

- Ibid.

- Adrien Dansette, Religious History of Modern France, vol. 2, Herder, Freiburg-Nelson, Edinburgh-London, 1961, p. 284

Posted February 18, 2026

______________________

______________________

Volume I |

Volume II |

Volume III |

Volume IV |

Volume V |

Volume VI |

Volume VII |

Volume VIII |

Volume IX |

Volume X |

Volume XI |

Special Edition |